Open Access | Research

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-ShareAlike 4.0 International License.

Nosocomial urinary tract infections in intensive care units in two tertiary hospitals

* Corresponding author: Ayoub Maaroufi

Mailing address: H Anesthesiology department, Moulay Ismail Military Hospital, Hassan II University Hospital, Fez, Morocco.

Email: maaroufiayoubmed@gmail.com

Received: 01 December 2025 / Revised: 11 December 2025 / Accepted: 24 December 2025 / Published: 30 December 2025

DOI: 10.31491/UTJ.2025.12.048

Abstract

Background:

Nosocomial urinary tract infections is a real public health problem due to their impact on morbidity, mortality, and healthcare costs. There are few studies that have examined their characteristics, especially in an intensive care setting. We are attempting to study their characteristics in two tertiary military hospitals in Morocco.

Methods:

This is a retrospective study conducted over 34 months in the intensive care unit (ICU) of the Moulay Imail Military hospital in Meknes (MIMH) and the 5th CMC in Errachidia.

Results:

We identified 122 cases of nosocomial urinary tract infection (NUN), with 90 cases in the first hospital and 32 in the second, with an incidence of 7.15% and 12.26%, respectively.

Conclusion:

his work highlights the complexity and heterogeneity of NUI in intensive care; the risk factors found in our study were urinary catheterization and local practices, both in terms of prevention and antibiotic therapy. Controlling these infections therefore requires a tailored approach, combining rigorous reinforcement of urinary catheter prevention bundles and rational antibiotic therapy programs adapted to the specific microbial ecology of each institution.

Keywords

Urinary tract infection, nosocomial infection, urinary catheterization

Introduction

Nosocomial urinary tract infections (NUI) are one of the most common complications in hospitals, particularly in intensive care units. They are a major public health problem due to their frequency, with urinary tract infections being among the most common bacterial infections, affecting approximately 150 million people each year [1, 2]. According to the Technical Committee on Nosocomial Infections (CTIN) and reiterated by the French-Language Society for Infectious Pathology (SPILF), an infection is considered nosocomial if it occurs during or following hospitalization and was neither present nor incubating at the start of treatment. A minimum period of 48 hours after admission is commonly accepted to define the nosocomial nature of an infection.

NUI account for 40% of all nosocomial infections and occur in 80% of cases among patients with indwelling urinary catheters (IUC) [3]. In Morocco, the epidemiological situation of nosocomial urinary tract infections is particularly concerning. A retrospective study conducted in the Nephrology Department of CHU Hassan II in Fez revealed an incidence of 16.9% of nosocomial urinary tract infections, with an average hospital stay of 14.1 days [4]. In this study, 80% of nosocomial urinary tract infections were complicated, reflecting the severity of the problem in Moroccan hospitals.

Our work is a retrospective study conducted over 34 months from February 2022 to December 2024 in the Anesthesia and Intensive Care Unit (ICU) of Moulay Ismail Military Hospital in Meknes (HMMI) and the 5th MedicalSurgical Center in Errachidia (5th CMC), involving 122 cases (90 and 32 cases respectively) of nosocomial urinary tract infections during hospitalization. The objective of our study is to evaluate the incidence of NUI in intensive care, analyze the clinical profile, identify risk factors, determine the main pathogens involved, and assess therapeutic approaches to improve management of urinary tract infections in ICU settings.

Materials and methods

This study is a retrospective analysis of the records of 122 cases of nosocomial urinary tract infection during hospitalization in the intensive care units of two military hospitals, HOPITAL MILITAIRE MOULAY ISMAIL in MEKNES (HMMI) and the 5th Medical-Surgical Center IN ERRACHIDIA (5th CMC), during the period over 34 months from February 2022 to December 2024. We have created an operating sheet that covers the various parameters required for our study.

Inclusion criteria

All patients hospitalized in the intensive care unit of HMMI and 5th CMC, whose hospitalization exceeds 48 hours.

Exclusion criteria: Patients hospitalized for ≤ 48 hours.

Sampling: The selection was made consecutively and nonprobabilistically.

Data collection tool

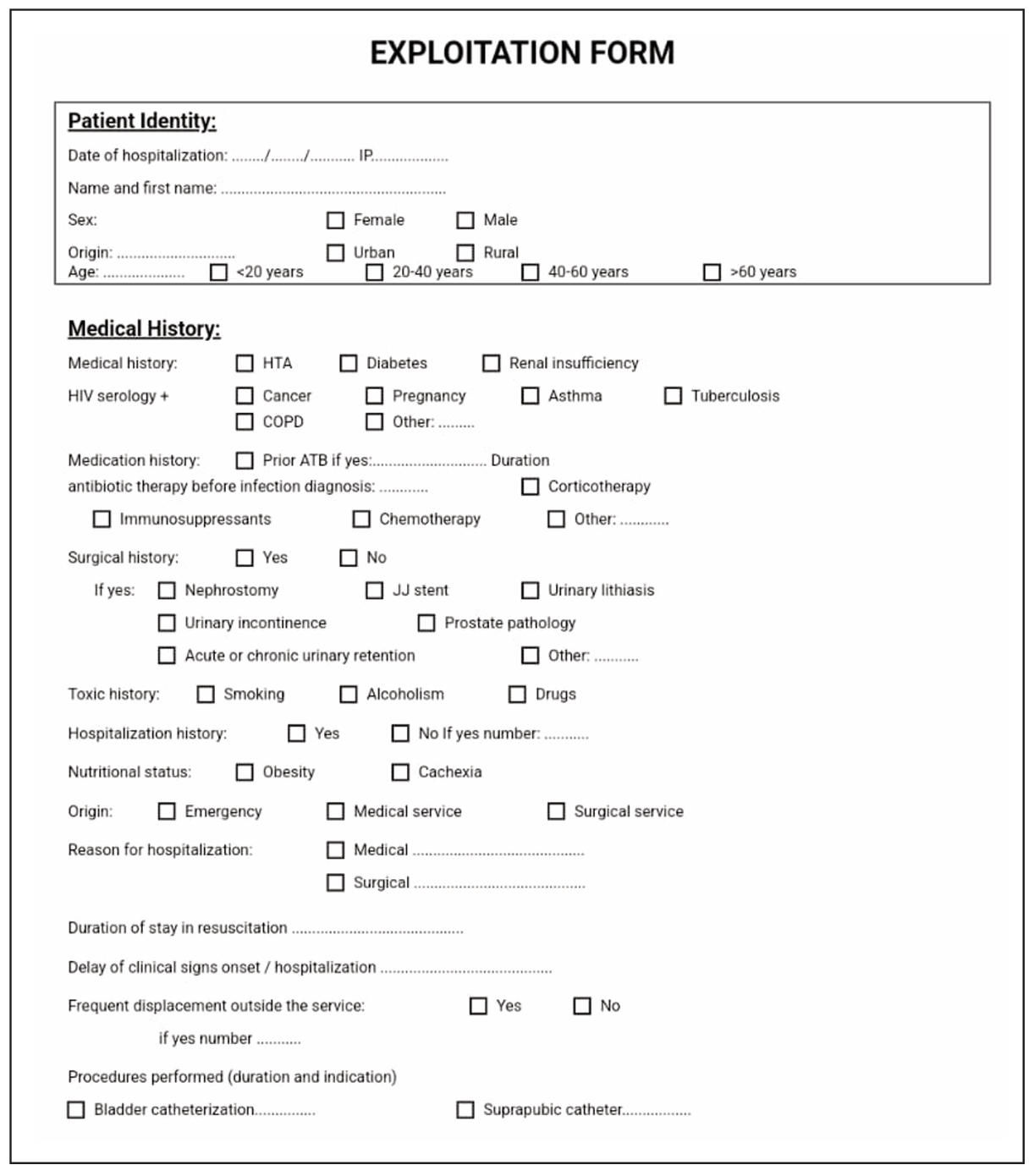

A standardized data collection form (Figure S1) was specifically designed for this study to ensure comprehensive and systematic data extraction. The operating sheet included the following variables:

1. Demographic data: Patient identification number (anonymized) - Age (in years) - Gender (Male/Female) - Date of admission to ICU Date of discharge from ICU.

2. Clinical parameters: Date of infection onset, Clinical signs and symptoms at diagnosis (Fever (temperature ≥ 38°C) - Turbid urine - Hematuria - Dysuria - Suprapubic pain - Asymptomatic bacteriuria).

3. Urinary catheterization data: Presence of urinary catheter (Yes/No) - Date of catheter insertion - Date of catheter removal Duration of catheterization (in days) - Type of catheter (closed system/open system) - Indication for catheterization.

4. Previous antibiotic therapy: Antibiotic agents used prior to NUI diagnosis Duration of antibiotic therapy - Indication for antibiotic use.

5. Microbiological data: Date of urine sample collection Type of sample (catheter specimen/midstream clean catch) - Urine culture results: - Isolated microorganism(s) - Colony count (CFU/mL) - Gram staining results - Antibiotic susceptibility testing results - Presence of multidrugresistant organisms.

6. Treatment and outcomes: Empirical antibiotic therapy initiated - Definitive antibiotic therapy based on culture results - Duration of treatment - Clinical response (improvement/no improvement) - Complications (septic shock, acute kidney injury) - Length of hospital stay (in days) - Outcome (discharge/death).

7. Prevention measures Compliance with hand hygiene protocols - Aseptic technique during catheter insertion - Daily catheter necessity assessment.

This comprehensive operating sheet was piloted on 10 medical records to ensure clarity, completeness, and feasibility before full-scale data collection commenced.

Data collection and analysis

Data were collected from the hospital’s patient medical records using a data collection form (Figure S2). Data analysis was performed using Excel software. For microbiological data, chi-square tests were performed to assess statistical significance of differences in pathogen distribu-tion between the two hospitals. Fisher’s exact test was used when expected cell counts were less than 5. A P-value < 0.05 was considered statistically significant. Relative risk (RR) with 95% confidence intervals (CI) was calculated for risk factors associated with NUI.

Results

Our work is a descriptive and retrospective study conducted over the period from February 1, 2022, to December 1, 2024, for a total duration of 34 months. It focused on 122 cases of nosocomial urinary tract infections (NUTIs) recorded in the intensive care units of the Moulay Ismaïl Military Hospital in Meknes (HMMI) and the 5th MedicalSurgical Center in Errachidia (5th CMC).

Our descriptive retrospective study covered 34 months (from February 1, 2022 to December 1, 2024), including 122 cases of nosocomial urinary tract infections (NUTIs) in the ICUs of HMMI and the 5th CMC.

The data analysis identified the distribution of gram-negative bacilli isolated from the CBEU (Cytobacteriological Examination of Urine) and their respective frequencies in both hospitals (Table 1).

Table 1.

Summary of NUTI characteristics at HMMI and 5th CMC.

| Elements studied | HMMI | 5th CMC | Statistical significance | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Nosocomial urinary tract infection (NUI) | -Number of cases | 90 | 32 | P = 0.004 |

| -Incidence | 7.15% | 12.26% | ||

| Gender distribution | -Men | 70% | 72% | P = 0.83 |

| -Women | 30% | 28% | ||

| -Sex ratio (M/F) | 2.55 | 2.33 | ||

| Length of hospital stay (median in days) | -Patients with NUI | 18.79 | 17.87 | P = 0.62 |

| -Patients without NUI | 10.95 | 7.49 | P = 0.001* | |

| Prevalence of urinary catheterizatio | -Patients surveyed (%) | 75% | 68.75% | P = 0.48 |

| -Average survey duration (days) | 13.5 | 10.95 | P = 0.17 | |

| Time to onset of infection (average in days) | 8.56 | 9.65 | P = 0.31 | |

| Symptoms (Percentage distribution) | -Isolated fever | 45% | 37.5% | P = 0.45 |

| -Fever + Turbid urine | 30% | 28.12% | ||

| -Fever + hematuria | 10% | 9.37% | ||

| -Asymptomatic | 5% | 3.12% | ||

| Previous antibiotic therapy | -General | 74.5% | 68.75% | P = 0.52 |

| -Amoxicillin + clavulanic acid | 45% | 36% | P = 0.36 | |

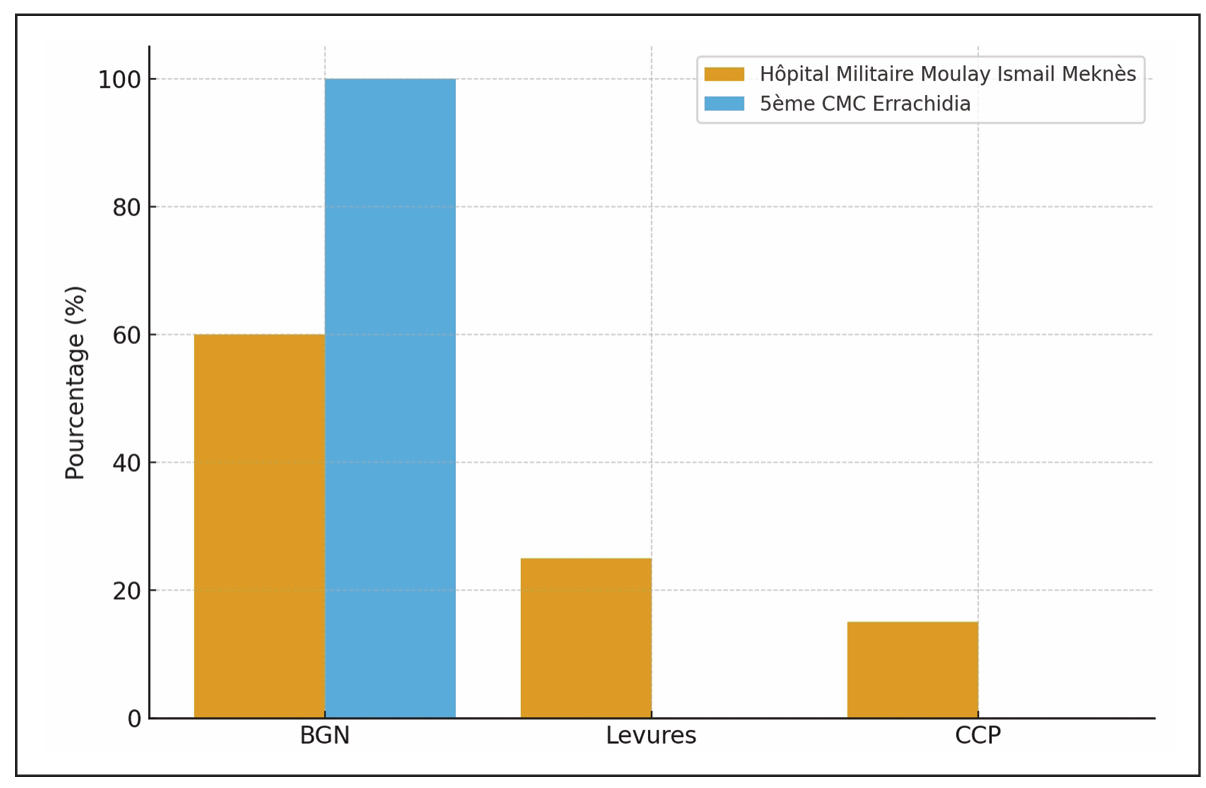

| Isolated germs on CBEU (%) | -Gram-negative bacilli (GNB) | 60% | 100% | |

| -Fungi | 25% | 0% | ||

| -Gram-positive cocci | 15% | 0% | ||

Note: *Statistically significant (P < 0.05).

Microbiological profile

The data analysis identified significant differences in the distribution of microorganisms isolated from urine cultures between the two hospitals (Table 2, Figure 1). The microbiological profile revealed highly significant differences between the two centers (χ2 = 34.7, P < 0.001). HMMI demonstrated a polymorphic microbial ecology with GNB predominance (60%), followed by fungi (25.6%) and GPC (14.4%). In contrast, 5th CMC showed 100% GNB exclusivity, with complete absence of fungi and GPC. Among GNB at HMMI, Escherichia coli was the most common isolate (32.2%), followed by Klebsiella pneumoniae < (16.7%). At 5th CMC, E. coli represented 50% of all isolates and K. pneumoniae 31.25%, together accounting for over 80% of all infections (RR = 2.1, 95% CI: 1.4-3.2, P < 0.001). The prevalence of fungal infections at HMMI (25.6%) was significantly associated with prior broad-spectrum antibiotic use (RR = 3.8, 95% CI: 2.1-6.9, P < 0.001). Among the 23 fungal isolates, Candida albicans predominated (78.3%).

Figure 1. Distribution of isolated germs from CBEU at HMMI and 5th CMC.

Table 2.

Microbiological distribution of isolated pathogens.

| Isolated pathogen | HMMI (n = 90) | 5th CMC (n = 32) | P-value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Gram-negative bacilli (GNB) | 54 (60%) | 32 (100%) | P < 0.001** |

| -Escherichia coli | 29 (32.2%) | 16 (50%) | P = 0.07 |

| -Klebsiella pneumoniae | 15 (16.7%) | 10 (31.25%) | P = 0.08 |

| -Pseudomonas aeruginosa | 7 (7.8%) | 4 (12.5%) | P = 0.42 |

| -Proteus mirabilis | 3 (3.3%) | 2 (6.25%) | P = 0.42 |

| Fungi | 23 (25.6%) | 0 (0%) | P = 0.001** |

| -Candida albicans | 18 (20%) | 0 (0%) | P = 0.005** |

| -Candida non-albicans | 5 (5.6%) | 0 (0%) | P = 0.18 |

| Gram-positive cocci (GPC) | 13 (14.4%) | 0 (0%) | P < 0.02* |

| -Enterococcus spp. | 9 (10%) | 0 (0%) | P = 0.06 |

| -Staphylococcus spp. | 4 (4.4%) | 0 (0%) | P =0.29 |

Note: *Statistically significant (P < 0.05), **Highly statistically significant (P < 0.001).

Discussion

Our work is a retrospective study covering the period from February 1, 2022, to December 1, 2024, focusing on 122 cases of nosocomial urinary tract infections (NUI) in the ICU of the Moulay Ismail Military Hospital in Meknes (HMMI) and the 5th CMC in Errachidia. The aim of this study was to highlight distinct epidemiological and microbiological profiles, emphasizing the major influence of local practices on the occurrence of these infections.

The overall prevalence rate of 7.15% at HMMI falls within the lower range of data reported by international surveillance networks for intensive care units, which typically vary between 5% and 15% [5, 6]. In contrast, the rate of 12.26% observed at the 5th CMC is significantly higher (P = 0.004) and resembles the most concerning figures in the literature, signaling a potentially more acute public health issue in this facility [7, 8]. These findings are consistent with the landmark EPIC study conducted across 17 European countries, which reported nosocomial infection rates varying significantly between centers and countries [9].

This disparity between centers is all the more significant given that it contrasts with data on urinary catheterization, the main risk factor for UTI [10, 11]. Although the percentage of patients catheterized and the average duration of catheterization are slightly higher in HMMI (75% and 13.5 days) compared to 5th CMC (68.75% and 10.95 days), the incidence of NUIs is conversely lower. This paradox suggests, as previous studies have pointed out, that simply quantifying catheterization is insufficient and that the quality of practices, strict aseptic technique during insertion, daily maintenance, and, above all, a policy of early removal play a key role [12].

An audit of practices at the 5th CMC therefore appears to be a priority in order to identify vulnerabilities in the care chain. The impact of these infections on morbidity is also dramatically confirmed by the lengthening of hospital stays, which is almost doubled for patients with NUIs in both centers (from 10.95 to 18.79 days in Meknes; P < 0.001), a result that perfectly aligns with numerous studies quantifying the added financial burden, measured in hospital-days, caused by healthcare-associated infections [13].

Microbiological analysis is the most salient aspect of our work, revealing a statistically significant ecological divergence between the two sites (P < 0.001). In Meknes, the profile is “polymorphic,” characteristic of an ICU subject to strong antibiotic selection pressure. The predominance of gram-negative bacilli (GNB) at 60%, led by Escherichia coli (32.5%), is a classic result [14]. However, the high proportion of yeasts (25.6%) and gram-positive cocci (GPC, 14.4%) is particularly instructive and statistically significant compared to 5th CMC (P < 0.001 and P = 0.02, respectively).

The high incidence of yeast infections is directly correlated with previous exposure to broad-spectrum antibiotics (P < 0.001), a well-documented phenomenon [15]. Our study shows that 74.4% of patients had received antibiotic therapy prior to the NUI, with amoxicillin-clavulanic acid being the most commonly prescribed (45%). The latter is known to select fungal flora, which probably explains this result. The latter is known to select fungal flora, which probably explains this result. Osawa et al. reported that 97.1% of ICU patients with candiduria had received antibiotics, with cefazolin and meropenem being the most commonly used agents [16]. The significant presence of Enterococci (10%) and staphylococci (4.4%) completes this picture of a complex microbial ecology, shaped by the intensive use of antibiotics. The emergence of these gram-positive cocci in the ICU setting has been strongly associated with the widespread use of broad-spectrum antibiotics, particularly third-generation cephalosporins and carbapenems, which exert selective pressure favoring resistant enterococcal and staphylococcal strains [17, 18]. In contrast, 5th CMC’s profile is “monolithic” and atypical, with 100% GNB exclusivity (P < 0.001 compared to HMMI). The total absence of GPC and yeasts is rarely reported in modern intensive care literature. Two main hypotheses must be considered. The first, methodological in nature, would be a laboratory bias: do culture techniques favor the detection of GNB at the expense of other germs, or are the latter systematically considered contaminants? A verification of microbiological protocols is therefore essential to validate this result. The second hypothesis, epidemiological in nature, posits the existence of a unique local bacterial ecology, where endemic circulation of GNB strains (E. coli and Klebsiella pneumoniae alone account for 81.25% of isolates; P < 0.001) and a specific antibiotic therapy policy exert a selection pressure that spares only these entities.

At the same time, the very high proportion of patients who received antibiotic therapy prior to diagnosis of NUI (nearly 70-75% in both centers) is a major cause for concern. It reflects intense selection pressure, which drives the emergence of resistance and colonization by opportunistic pathogens. These observations strongly support the implementation or reinforcement of antibiotic stewardship programs, focused on the reassessment of probabilistic treatments and therapeutic de-escalation [19].

However, this study has several limitations inherent to its retrospective design, including the risk of missing or incomplete data and the inability to establish a formal causal relationship between risk factors and infection occurrence. The absence of comprehensive antimicrobial resistance data limited a more detailed evaluation of prescribing practices and the formulation of robust empirical treatment recommendations. In addition, not all potential confounding variables influencing infection rates could be controlled, and a degree of selection bias may have occurred due to reliance on medical record documentation. Finally, the conduct of the study exclusively in military hospitals may restrict the generalizability of the findings to civilian healthcare settings. Nevertheless, despite these limitations, the statistically significant results provide valuable insights into the epidemiology and microbiological characteristics of nosocomial urinary tract infections in Moroccan intensive care units.

Prevention measures and recommendations

• Avoid unnecessary catheterization: Do not treat bladder catheterization as a trivial procedure for the convenience of nursing staff or even the patient.

• Remove any urinary catheter as soon as it is no longer strictly necessary, taking into account the relationship between the risk of infection and the duration of catheterization.

• Raise awareness among healthcare staff about hospital hygiene and the risk of hand-borne transmission of IUN: Ongoing training, written protocols, and compliance with aseptic measures when inserting and maintaining urinary catheters.

• Perform under strict conditions of asepsis and sterility. Securely attach the catheter.

• Maintain a closed system: It is strictly forbidden to disconnect the urinary catheter from the drainage system.

• Use dual-flow catheters if bladder irrigation is essential.

• Establish continuous urinary drainage to prevent urinary stasis.

• Collect urine samples in a strictly aseptic manner for cytological and bacteriological examination (CBEU).

• Check that urine flow is regular to prevent any obstruction to urinary flow, which could lead to potential stasis.

Conclusions

Nosocomial urinary tract infections represent a real public health problem due to their impact on morbidity, mortality, and healthcare costs. In our retrospective descriptive study in the ICU of two tertiary hospitals, 7.15% and 12.26% of patients hospitalized in the two hospitals, respectively, had developed a UTI. The main risk factors are bladder catheterization, prior antibiotic therapy, and failure to comply with aseptic techniques when caring for urinary catheters. Urinary tract infections can be asymptomatic or progress to severe forms, including septic shock, or promote the emergence of multidrug-resistant organisms.

Prevention remains the best strategy to reduce their incidence and associated complications. It relies on the rationalization of antibiotic use in both hospital and outpatient settings, notably through raising awareness about the dangers of self-medication, training healthcare staff, adhering to catheterization guidelines, and implementing aseptic measures

Declarations

Author contributions

Conceptualization: Moncef ELazrak. Investigation: Ayoub Ouchen. Methodology: Maaroufi Ayoub. Validation: Jaouad Laoutid. Writing – original draft: Moncef ELazrak; Maaroufi Ayoub; Taoufik el Akef.Writing – review & editing: Hicham Kechna.

Financial support and sponsorship

None.

Ethical considerations

Ethical aspects were also taken into consideration: respect for the anonymity of study participants, respect for the confidentiality of results.

Conflicts of interest

The authors declare that they have no competing interests regarding the publication of this paper. All authors of the manuscript have read and agreed to its content and are accountable for all aspects of the accuracy and integrity of the manuscript.

References

1. Öztürk R, & Murt A. Epidemiology of urological infections: a global burden. World J Urol, 2020, 38(11): 26692679. [Crossref]

2. Tandogdu Z, & Wagenlehner F. Global epidemiology of urinary tract infections. Curr Opin Infect Dis, 2016, 29(1): 73-79. [Crossref]

3. Gavazzi G, & Krause K. Ageing and infection. Lancet Infect Dis, 2002, 2(11): 659-666. [Crossref]

4. Lazrak M, El Bardai G, Jaafour S, Kabbali M, Arrayhani M, & ST H. Profil de l’infection urinaire nosocomiale dans un service de néphrologie. Pan African Medical Journal, 2014, 19(59): 4835-4847. [Crossref]

5. Control ECfDPa. “Surveillance of healthcare-associated infections and prevention indicators in European intensive care units: HAI-Net ICU protocol, version 2.2.” from https://www.ecdc.europa.eu/en/publicationsdata/surveillance-healthcare-associated-infections-andprevention-indicators-european.

6. Weinstein R. Epidemiology and control of nosocomial infections in adult intensive care units. Am J Med, 1991, 91(3b): 179s-184s. [Crossref]

7. Hooton T, Bradley S, Cardenas D, Colgan R, Geerlings S, Rice J, et al. Diagnosis, prevention, and treatment of catheter-associated urinary tract infection in adults: 2009 International Clinical Practice Guidelines from the Infectious Diseases Society of America. Clin Infect Dis, 2010, 50(5): 625-663. [Crossref]

8. Commission. CE (2015). “Catheter Associated Urinary Tract Infections (CAUTIs): Prevention Guidelines. Sydney: NSW Health; 2015.”. from http://www.cec.health.nsw.gov.au/patient-safety-programs/adult-patient-safety/cauti-prevention.

9. Vincent J, Bihari D, Suter P, Bruining H, White J, NicolasChanoin M, et al. The prevalence of nosocomial infection in intensive care units in Europe. Results of the European Prevalence of Infection in Intensive Care (EPIC) Study. EPIC International Advisory Committee. JAMA, 1995, 274(8): 639-644.

10. Stone P, Braccia D, & Larson E. Systematic review of economic analyses of health care-associated infections. Am J Infect Control, 2005, 33(9): 501-509. [Crossref]

11. Leone M, Albanèse J, Garnier F, Sapin C, Barrau K, Bimar M, et al. Risk factors of nosocomial catheter-associated urinary tract infection in a polyvalent intensive care unit. Intensive Care Med, 2003, 29(7): 1077-1080. [Crossref]

12. Foxman B. Epidemiology of urinary tract infections: incidence, morbidity, and economic costs. Am J Med, 2002, 113 Suppl 1A: 5s-13s. [Crossref]

13. Tissot E, Limat S, Cornette C, & Capellier G. Risk factors for catheter-associated bacteriuria in a medical intensive care unit. Eur J Clin Microbiol Infect Dis, 2001, 20(4): 260-262. [Crossref]

14. Richards M, Edwards J, Culver D, & Gaynes R. Nosocomial infections in combined medical-surgical intensive care units in the United States. Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol, 2000, 21(8): 510-515. [Crossref]

15. Bouza E, San Juan R, Muñoz P, Voss A, & Kluytmans J. A European perspective on nosocomial urinary tract infections II. Report on incidence, clinical characteristics and outcome (ESGNI-004 study). European Study Group on Nosocomial Infection. Clin Microbiol Infect, 2001, 7(10):532-542. [Crossref]

16. Osawa K, Shigemura K, Yoshida H, Fujisawa M, & Arakawa S. Candida urinary tract infection and Candida species susceptibilities to antifungal agents. J Antibiot (Tokyo), 2013, 66(11): 651-654. [Crossref]

17. Arias C, & Murray B. The rise of the Enterococcus: beyond vancomycin resistance. Nat Rev Microbiol, 2012, 10(4): 266-278. [Crossref]

18. Remschmidt C, Schneider S, Meyer E, Schroeren-Boersch B, Gastmeier P, & Schwab F. Surveillance of Antibiotic Use and Resistance in Intensive Care Units (SARI). Dtsch Arztebl Int, 2017, 114(50): 858-865. [Crossref]

19. Dellit T, Owens R, McGowan J, Jr., Gerding D, Weinstein R, Burke J, et al. Infectious diseases society of America and the society for healthcare epidemiology of America guidelines for developing an institutional program to enhance antimicrobial stewardship. Clin Infect Dis, 2007, 44(2): 159-177. [Crossref]

SUPPLEMENTARY

Supplementary Figure 1. Operating data sheet.

Supplementary Figure 2. Data collection form.