Open Access | Case Report

This work is licensed under a Creative

Commons Attribution-ShareAlike 4.0 International License.

Preoperative 3D model guidance for robotic-partial nephrecto- my: a case report of intraoperative vascular injury and its man- agement

# These authors contributed equally to the first authorship.

* Corresponding author: Gabriele Volpi

Mailing address: Department of Surgery, Candiolo Cancer Institute, FPO-IRCCS, Strada Provinciale 142, km 3,95 10060 Candiolo, Turin, Italy.

Email: gabriele.volpi@ircc.it

This article belongs to the Special Issue: Nightmare and complex cases in Urology

Received: 19 January 2023 / Revised: 27 April 2023 / Accepted: 05 May 2023 / Published: 30 June 2023

DOI: 10.31491/UTJ.2023.06.009

Abstract

Partial nephrectomy (PN) is increasingly used in the treatment of renal cell carcinoma and is now considered the “gold standard” treatment for T1 lesions. However, it is still considered a challenging procedure. Several imaging modalities have been tested to improve PN outcomes. One of the most intriguing is 3D reconstruction, which can be used for both preoperative planning and intraoperative decision making. In the following case, we describe an intraoperative vascular injury that occurred during robot-assisted PN (RAPN), despite accurate preoperative 3D-guided planning, and its management. The patient undergoing PN was 57 years old and had an incidental diagnosis of a 17 mm left-sided renal lesion located on the posterior surface of the kidney at the lower pole. Based on the CT scan, a virtual 3D reconstruction was obtained, which highlighted the presence of a saccular dilatation of the main artery. Selective clamping of a segmental artery feeding the posterior surface of the lower pole of the kidney was planned. The RENAL nephrometry and PADUA score were calculated with a value of 4p and 6, respectively. Despite a thorough preoperative planning, a lesion of the dilatation of the main artery was identified with a large bleeding which was managed by global clamping of the kidney followed by selective suturing. In conclusion, PN remains a challenging procedure even for experienced and skilled surgeons. The occurrence of intraoperative complications is not anecdotal. The introduction of the robotic console and new intraoperative tools such as 3D models have reduced the risk of adverse events, but their complete elimination is still utopian due to the extreme complexity of the procedure.

Keywords

Robotic partial nephrectomy; 3D models; nightmares; kidney cancer

Introduction

Nephron-sparing surgery (NSS) is being increasingly adopted for the treatment of renal cell carcinoma and is now

considered the “gold standard” treatment for T1 lesions [1].

Indeed, in such tumors, the oncologic outcomes of NSS

are similar to those of radical nephrectomy (RN) [1], with

better functional recovery [2]. However, this procedure

has historically been considered challenging and reserved

for skilled and experienced surgeons, mainly due to safety

concerns: Indeed, PN is associated with a higher incidence

of postoperative complications compared to RN, especially the most severe ones (Clavien-Dindo classification

grade ≥3) [3]. In recent years, the increasing use of the

robotic platform has allowed to improve the perioperative outcomes of partial nephrectomy (PN) [4]. However,

despite technical and technological developments, the approach to complex tumors remains an open question. The

complexity of the procedure can be increased by several

factors, such as the presence of endophytic lesions, which

are difficult to visualize on the organ surface, the location on the posterior surface of the kidney, which requires

medialization and rotation of the organ before starting the

resection phase, and finally the complexity of the renal

pedicle. In recent years, several imaging modalities have

been tested to improve PN outcomes [5-8]. Among them,

one of the most intriguing is certainly the 3D reconstruction, which can be used for both preoperative planning

and intraoperative decision making [9].

Herein, we present a case report of intraoperative vascular

injury that occurred during robot-assisted PN (RAPN)

despite accurate preoperative 3D-guided planning and its

management.

Case report

3D models creation

Specifically for this clinical case, we created a 3D reconstruction of the kidney following a rigorous approach [10].

The first step is to upload contrast-enhanced computed

tomography (C.E. CT) DICOM images to a dedicated

and authorized cloud platform (www.mymedics3d.com).

Using the visualization software, it is then possible to

select and analyze a specific organ, extrapolate the most

useful images (e.g., arterial or late phase images of a CT

scan), and modify and adjust specific parameters (e.g.,

image contrast and brightness). This is the “preprocessing” phase. Next, a rendering of the organ is created and

segmentation is performed semi-automatically by dedicated software. Finally, the 3D model obtained is carefully

analyzed and refined by a biomedical engineer under the

supervision of the urologist. The aim is to obtain a highly

accurate 3D model that reproduces the organ, the lesion,

the vessels and the intraparenchymal structures. The final

steps in the process are the creation of a transcription code

to visualize the reconstruction in an interactive 3D PDF

format. Then, on the same cloud platform, virtual reconstructions can be downloaded and viewed for both preoperative planning and intraoperative decision making.

The production of such models requires close cooperation

between urologists, radiologists and dedicated bioengineers. The current price for each model is around 800

euros, while the entire production process takes around

48 hours. In the near future, part of the process will be

automated, which will reduce both the cost and the time

required to produce the models. These improvements will

further expand the applications and availability of this

technology, making it virtually “on-demand” in the operating room, based on surgeons’ requests.

Case description

We present the case of a non-smoking 57-year-old woman

with a history of hypertension who was referred to our

urology department for recurrent cystitis and a single episode of hematuria. For the diagnostic evaluation, she underwent cystoscopy, which revealed no suspicious bladder

lesion, and C.E. CT, which showed a 17 mm inhomogeneous lesion on the posterior surface of the lower pole of

the left kidney that warranted further evaluation. The patient then underwent Magnetic Resonance Imaging (MRI),

which confirmed the presence of a suspicious lesion that

warranted surgical treatment. The patient was then scheduled for a robot-assisted partial left nephrectomy (RAPN).

The patient had a BMI of 33.1 and a Charlson’s Comorbidity Index of 3. Preoperative serum creatinine and eGFR

were 0.92 mg/dL and 62.9 mL/min/1.73m2, respectively.

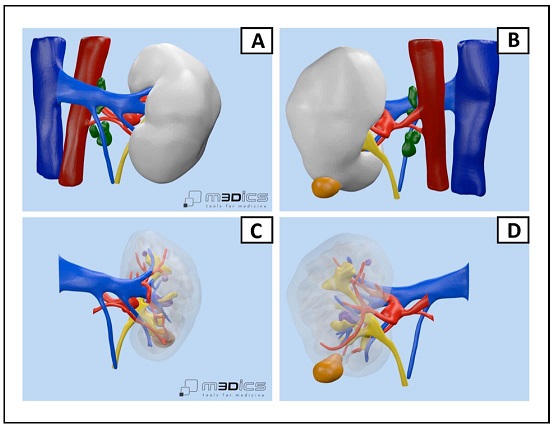

Preoperatively, the CT scan (Figure 1) was carefully

evaluated and a 3D virtual reconstruction of the case was

obtained (Figure 2) using the technique described above.

The 3D model showed the presence of two renal arteries:

the main one directed to the hilum and a second collateral

artery directed to the anterior surface of the lower pole of

the kidney, both originating from the aorta. The main artery was characterized by a saccular dilatation just proximal to a bifurcation for the segmental arteries. Based on

the 3D model obtained, selective clamping of the inferior

branch of the main artery bifurcation was planned preoperatively to minimize the impact of ischemic damage on

postoperative renal function. RENAL nephrometry and

PADUA score were calculated with a value of 4p and 6,

respectively. Based on these results, we decided to use the

3D model for preoperative planning only.

Figure 1. C.E. CT showing the presence of an inhomogeneous lesion on the posterior surface of the lower pole of the left kidney.

Figure 2. The 3D model obtained from the preoperative CT: (A) anterior view of the kidney; (B) posterior view of the kidney; (C) anterior view of the kidney with parenchymal transparency; (D) posterior view of the kidney and its vessels, saccular dilatation of the main artery.

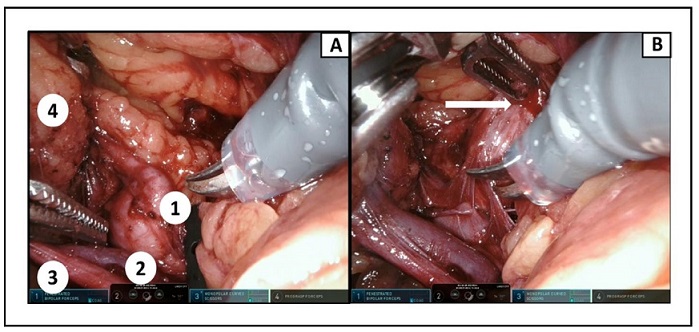

We then proceeded with the dissection of the renal hilum, a critical step in the procedure (Figure 3A). During the dissection of the arterial vessel directed to the lower pole of the kidney, a focal lesion of the saccular dilatation of the main artery was noted (Figure 3B).

Figure 3. Intraoperative view of the renal pedicle: (A) Dissection of various structures: 1) dilatation of the main artery; 2) renal vein; 3) ureter; 4) kidney; (B) the dilatation of the main artery is inadvertently injured by the robotic grasp.

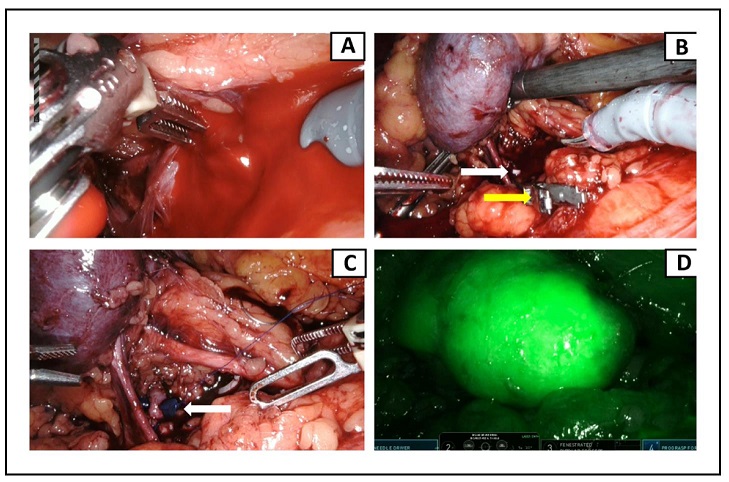

Figure 4. (A) Artery’s violation caused immediate massive hemorrhage; (B) a Weck clip (white arrow) is quickly placed upstream of the bleeding site, stopping the bleeding. A vascular clamp (yellow arrow) is then placed on the healthy renal artery, allowing the surgeon to perform the subsequent vascular suture; (C) a single monofilament running suture is placed over the injured segment of the artery. At the end of the procedure, the suture is secured with a resorbable clip (white arrow); (D) indocyanine green is injected to verify complete revascularization of the kidney.

Discussion

PN has historically been considered a challenging procedure, but in recent years, with the introduction of the

robotic console and refinement of surgical techniques, the

organ-sparing approach has been widely adopted and is

now considered the first-line indication for cT1 renal tumors [1].

However, the occurrence of intraoperative complications in PN is not an anecdotal event. As reported in the

RECORd1 project, which collected data on partial nephrectomies performed in Italy between 2009 and 2012

using different surgical approaches (laparoscopic, open

and robotic), the rate of intraoperative complications was

5% [11]. On the other hand, RAPN allows to reduce this

risk to 2.6% of the procedures [12]. Focusing on vascular

injury, this adverse event occurred in approximately 1%

of the procedures and was usually managed with direct

suture of the bleeding vessel, while conversion to radical

nephrectomy was rarely performed [11].

The complication rate of RAPN is influenced by several

factors, such as the skill of the surgeon and the aspect of the tumor. Surgical experience is certainly associated with a progressive decrease in complications, as has

been widely demonstrated. In fact, Mottrie et al. showed

that increasing surgeon experience was correlated with a

progressive decrease in warm ischemia time, total operative time, and EBL [13]. These findings were confirmed

by both Mathieu et al. and Ficarra et al. who highlighted

that the relative risk of perioperative complications was

2.14 and 2.99 for the first 20 and 30 cases, respectively

[14, 15]. In addition, some non-modifiable factors such as

lesion characteristics are also associated with the occurrence of surgical complications. In fact, two scores have

been validated to define tumor complexity: the RENAL

nephrometry score and the PADUA classification. These

scores showed a correlation with the occurrence of surgical complications during PN, with a four times higher risk

of adverse events in case of RENAL score > 9 or PADUA

> 10 [16]. Specifically for the robotic approach, the RENAL score seems to be associated with higher overall and

major complication rates. In fact, Tanagho et al. demonstrated that in patients undergoing RAPN, increasing RENAL scores of 4-6, 7-9, and 10-12 were associated with

progressively increasing complication rates of 11, 18, and

23%, respectively [12]. These results were confirmed by

Simhan et al. who highlighted that in patients undergoing PN, of which almost 50% underwent RAPN, RENAL

scores of 4-6, 7-9, and 10-12 were associated with progressively increasing major complication rates of 6, 11,

and 22%, respectively [17]. Finally, tumor size was also

found to be an independent predictor of complications,

with a small but statistically significant correlation with

perioperative complications after RAPN [16].

In recent years, the introduction of the use of 3D virtual

models has further improved the accuracy of predicting

complications of the above classifications. In fact, our

group demonstrated that in a cohort of 101 patients, the

preoperative assessment of PADUA and RENAL nephrometry scores with the 3D reconstructions showed a

downgrading in 48.5% and 52.4% of cases, respectively,

compared to those defined based on two-dimensional imaging. Similar results were obtained for the nephrometry

categories. It is important to emphasize that 3D-based

nephrometry scores and categories showed a higher accuracy in predicting postoperative complications compared

to those based on two-dimensional imaging [18].

In addition, the use of 3D virtual models has refined the

ability to understand the surgical anatomy before and during PN, with the goal of improving both the oncologic and

functional outcomes of the surgical procedure. 3D models

can be used during preoperative planning as well as during the intraoperative decision-making process. Throughout the intraoperative phase, 3D models can be used in a

cognitive manner, consulting the 3D model in real time on

a digital support placed next to the robotic console, or for

augmented reality (AR) procedures, overlaying the 3D reconstruction on the patient’s real anatomy. Our group has

already published several experiences with these technologies, showing promising results. In fact, we have highlighted that preoperative planning with 3D reconstructions determines a better grasp of the vascular anatomy, reducing the rate of global clamping. In a previously published

study comparing RAPN performed with and without

3D reconstructions, we demonstrated that a significantly

higher rate of patients underwent global ischemia in the

no 3D group (80.6% vs. 23.8%) [19]. Furthermore, in the

3D group, 90.5% of the procedures were performed with

an intraoperative approach to the renal pedicle according

to the preoperative plan. In these cases, the tumor resection bed was almost completely bloodless, indicating an

effective selection of the clamped arterial branch. Further

evidence of successful clamping was obtained with nearinfrared fluorescence, confirming our findings.

Regarding the use of 3D models in AR procedures, we

have demonstrated their usefulness in the identification

of complex tumors, especially endophytic or posteriorly

located lesions during transperitoneal PN, which resulted

in an easier and faster procedure [20]. In addition, the 3D

models allowed the identification of “hidden” intraparenchymal structures such as vessels and calyces, allowing

selective management during the resection phase of the

procedure. Moreover, such structures were also identified

at the end of the excision phase, at the level of the resection bed, allowing the execution of dedicated sutures of

both vessels and calyces in case of injury.

Notwithstanding the low clinical evidence of our work,

these experiences demonstrate how nephrometry scores

and the use of 3D model might help to improve the management of renal cell carcinoma candidates for NSS.

However, PN is still a challenging procedure and the risk

of surgical complications is always present.

Conclusions

PN remains a challenging procedure even for experienced and skilled surgeons, and the occurrence of intraoperative complications is not uncommon. The introduction of the robotic console and the use of 3D virtual models have reduced the risk of adverse events, but they will never be eliminated due to the intrinsic complexity of certain renal lesions and the heterogeneity of the vascular anatomy.

Declarations

Financial support and sponsorship

None.

Conflicts of interest

The authors report no conflicts of interest.

Ethical approval and consent to participate

All procedures performed in studies involving human participants were in accordance with the ethical standards of the institutional and/or national research committee and with the 1964 Helsinki declaration and its later amendments or comparable ethical standards. Informed consent was obtained from the patient.

Availability of data and materials

Not applicable.

References

1. Ljungberg B, Albiges L, Abu-Ghanem Y, Bedke J, Capitanio U, Dabestani S, et al. European Association of Urology Guidelines on Renal Cell Carcinoma: The 2022 Update. Eur Urol, 2022, 82(4): 399-410.[Crossref]

2. Scosyrev E, Messing EM, Sylvester R, Campbell S, & Van Poppel H. Renal function after nephron-sparing surgery versus radical nephrectomy: results from EORTC randomized trial 30904. Eur Urol, 2014, 65(2): 372-377. [Crossref]

3. Hadjipavlou M, Khan F, Fowler S, Joyce A, Keeley FX, & Sriprasad S. Partial vs radical nephrectomy for T1 renal tumours: an analysis from the British Association of Urological Surgeons Nephrectomy Audit. BJU Int, 2016, 117(1): 62-71. [Crossref]

4. Leow JJ, Heah NH, Chang SL, Chong YL, & Png KS. Outcomes of Robotic versus Laparoscopic Partial Nephrectomy: an Updated Meta-Analysis of 4,919 Patients. J Urol, 2016, 196(5): 1371-1377. [Crossref]

5. Secil M, Elibol C, Aslan G, Kefi A, Obuz F, Tuna B, et al. Role of intraoperative US in the decision for radical or partial nephrectomy. Radiology, 2011, 258(1): 283-290. [Crossref]

6. Qin B, Hu H, Lu Y, Wang Y, Yu Y, Zhang J, et al. Intraoperative ultrasonography in laparoscopic partial nephrectomy for intrarenal tumors. PLoS One, 2018, 13(4): e0195911. [Crossref]

7. Krane LS, Manny TB, & Hemal AK. Is near infrared fluorescence imaging using indocyanine green dye useful in robotic partial nephrectomy: a prospective comparative study of 94 patients. Urology, 2012, 80(1): 110-116. [Crossref]

8. Veccia A, Antonelli A, Hampton LJ, Greco F, Perdonà S, Lima E, et al. Near-infrared Fluorescence Imaging with Indocyanine Green in Robot-assisted Partial Nephrectomy: Pooled Analysis of Comparative Studies. Eur Urol Focus, 2020, 6(3): 505-512. [Crossref]

9. Porpiglia F, Amparore D, Checcucci E, Autorino R, Manfredi M, Iannizzi G, et al. Current Use of Threedimensional Model Technology in Urology: A Road Map for Personalised Surgical Planning. Eur Urol Focus, 2018, 4(5): 652-656. [Crossref]

10. Checcucci E, Amparore D, Pecoraro A, Peretti D, Aimar R, S DEC, et al. 3D mixed reality holograms for preoperative surgical planning of nephron-sparing surgery: evaluation of surgeons’ perception. Minerva Urol Nephrol, 2021, 73(3): 367-375. [Crossref]

11. Minervini A, Mari A, Borghesi M, Antonelli A, Bertolo R, Bianchi G, et al. The occurrence of intraoperative complications during partial nephrectomy and their impact on postoperative outcome: results from the RECORd1 project. Minerva Urol Nefrol, 2019, 71(1): 47-54. [Crossref]

12. Tanagho YS, Kaouk JH, Allaf ME, Rogers CG, Stifelman MD, Kaczmarek BF, et al. Perioperative complications of robot-assisted partial nephrectomy: analysis of 886 patients at 5 United States centers. Urology, 2013, 81(3): 573-579. [Crossref]

13. Larcher A, Muttin F, Peyronnet B, De Naeyer G, Khene ZE, Dell’Oglio P, et al. The Learning Curve for Robot-assisted Partial Nephrectomy: Impact of Surgical Experience on Perioperative Outcomes. Eur Urol, 2019, 75(2): 253-256. [Crossref]

14. Mathieu R, Verhoest G, Droupy S, de la Taille A, Bruyere F, Doumerc N, et al. Predictive factors of complications after robot-assisted laparoscopic partial nephrectomy: a retrospective multicentre study. BJU Int, 2013, 112(4): E283-289. [Crossref]

15. Ficarra V, Bhayani S, Porter J, Buffi N, Lee R, Cestari A, et al. Predictors of warm ischemia time and perioperative complications in a multicenter, international series of robot-assisted partial nephrectomy. Eur Urol, 2012, 61(2): 395-402. [Crossref]

16. Hew MN, Baseskioglu B, Barwari K, Axwijk PH, Can C, Horenblas S, et al. Critical appraisal of the PADUA classification and assessment of the R.E.N.A.L. nephrometry score in patients undergoing partial nephrectomy. J Urol, 2011, 186(1): 42-46. [Crossref]

17. Simhan J, Smaldone MC, Tsai KJ, Canter DJ, Li T, Kutikov A, et al. Objective measures of renal mass anatomic complexity predict rates of major complications following partial nephrectomy. Eur Urol, 2011, 60(4): 724-730. [Crossref]

18. Porpiglia F, Amparore D, Checcucci E, Manfredi M, Stura I, Migliaretti G, et al. Three-dimensional virtual imaging of renal tumours: a new tool to improve the accuracy of nephrometry scores. BJU Int, 2019, 124(6): 945-954. [Crossref]

19. Porpiglia F, Fiori C, Checcucci E, Amparore D, & Bertolo R. Hyperaccuracy Three-dimensional Reconstruction Is Able to Maximize the Efficacy of Selective Clamping During Robot-assisted Partial Nephrectomy for Complex Renal Masses. Eur Urol, 2018, 74(5): 651-660.[Crossref]

20. Porpiglia F, Checcucci E, Amparore D, Piramide F, Volpi G, Granato S, et al. Three-dimensional Augmented Reality Robot-assisted Partial Nephrectomy in Case of Complex Tumours (PADUA ≥10): A New Intraoperative Tool Overcoming the Ultrasound Guidance. Eur Urol, 2020, 78(2): 229-238. [Crossref]