Open Access | Research

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-ShareAlike 4.0 International License.

No causal effect of olive oil consumption on Alzheimer’s disease: a two-sample Mendelian randomization with mediation and multivariable analyses

* Corresponding author: Muhammad Iqhrammullah

Mailing address: Postgraduate Program of Public Health, Universitas Muhammadiyah Aceh, Indonesia.

Email: m.iqhrammullah@gmail.com

Received: 25 September 2025 / Revised:23 October 2025 / Accepted: 05 November 2025 / Published: 30 December 2025

DOI: 10.31491/APT.2025.12.196

Abstract

Background: Observational links between olive oil and lower dementia risk may reflect confounding or survival bias. We tested whether olive oil consumption causally influences Alzheimer’s disease (AD) risk using Mendelian randomization (MR).

Methods: We performed two-sample MR using IEU OpenGWAS summary statistics. Genetic instruments for olive oil consumption were derived from a UK Biobank cooking-fat question (P < 5×10-6, LD-independent), explaining around 0.07% of exposure variance with mean F of around 24. The AD outcome was a large Europeanancestry GWAS including clinically diagnosed and proxy cases. The primary estimator was inverse-variance weighted (IVW), with MR-Egger, Cochran’s Q and leave-one-out analyses for sensitivity. Two-step MR tested mediation via lipid traits (LDL-C, HDL-C, triglycerides, apolipoprotein B, apolipoprotein A1), blood pressure and inflammatory markers. Multivariable MR (MVMR) adjusted for apolipoprotein B, adiposity, blood pressure, and systemic inflammation.

Results: There was no evidence that higher genetically proxied olive oil intake reduces AD risk. The IVW point estimate was effectively null, with confidence intervals excluding even modest benefits (for example, > 1% relative risk reduction per SD increase). Findings were robust across MR-Egger, heterogeneity tests and leaveone-out analyses, with no indication of horizontal pleiotropy. Mediation analyses showed no indirect effects through lipid profiles, vascular injury or inflammation. In MVMR, the olive oil coefficient remained close to null, and the adjusted effects of other traits were non-significant.

Conclusion: This comprehensive MR analysis does not support a causal neuroprotective effect of olive oil on AD. Any true effect, if present, is likely minimal. Observational associations may reflect confounding or healthy-user bias. While cardiovascular benefits justify olive oil as part of a heart-healthy diet, it should not be promoted as a stand-alone AD prevention strategy. Larger, ancestry-diverse datasets and gene–diet interaction analyses are warranted.

Keywords

Cognitive function, fatty acid, Mediterranean diet, cognitive decline, multivariable MR

Introduction

Alzheimer’s disease (AD) is a progressive neurodegenerative disorder and the most common cause of dementia in older adults. With population aging, the global burden of AD is increasing, contributing to deaths in about one-third of older adults [1]. In contrast to declining mortality rates for cardiovascular disease and stroke, dementia-related deaths have been increasing over the past decades [1]. This alarming trend has intensified the search for modifiable risk factors and preventive strategies for AD [2]. Dietary habits have garnered particular interest, as nutrition is a key lifestyle factor that might be targeted to promote healthy cognitive aging [3-5]. In particular, adherence to the Mediterranean diet, characterized by high consumption of plant-based foods and olive oil as the primary fat source, has been associated with potential benefits for brain health [2, 6]. A systematic review and meta-analysis comprised of 26 cohort studies and 2 randomized controlled trials (RCTs) concluded that Mediterranean diet may contribute to protective effect against mild cognitive impairment (MCI) and AD [6]. In multiple cohorts and several RCTs, olive oil consumption is attributed to lower risk of AD, though the effect is dependent on population subset and adjusting variable [7-10].

Traditional randomized controlled trials on diet and dementia have been limited by long follow-up durations and poor adherence [11]. On the other hand, Mendelian randomization (MR) offers a more robust approach to infer causality between olive oil consumption and AD risk by utilizing genetic variants as unconfounded proxies for dietary exposure [12, 13]. This design strengthens causal inference beyond what is possible in traditional observational studies [14]. An MR study by Wu et al. reported that olive intake reduced coronary heart disease risk, and was also associated with lower risk of myocardial infarction and heart failure [15]. Given the well-established links between cardiovascular health and dementia, we hypothesized that olive oil intake could indirectly benefit the brain health, thereby reducing risks in AD. The aim of this study was to perform a two-sample MR analysis for evaluating the causal effect of olive oil consumption on AD risk.

Methods

Study design and data sources

We used a two-sample MR design, analyzing summarylevel GWAS data for the exposure (olive oil consumption) and outcome (Alzheimer’s disease) from non-overlapping samples of European descent. The genetic instruments for olive oil consumption were obtained from the UK Biobank, a large population-based cohort. Specifically, we utilized genome-wide association results for the phenotype “Type of fat/oil used in cooking: Olive oil” (UKB field ID 1329), as made available by the MRC-IEU OpenGWAS project (GWAS ID: ukb-b-3875). This phenotype reflects participants’ self-reported primary cooking oil (with olive oil as one option) and can be considered a proxy for regular olive oil use in diet. The GWAS was conducted on 64,949 individuals of European ancestry in UK Biobank, with genotype imputation and association analysis performed by Neale et al. [16], where genetic effects are expressed per unit increase in olive oil use. We clumped the summary statistics to select independent top genetic variants for olive oil consumption. Variants were eligible as instruments if they reached a relaxed genome-wide significance threshold of p of less than 5 × 10-6. SNPs were clumped at linkage disequilibrium (LD) threshold r2 < 0.001 within a 10,000 kb window using the 1000 Genomes European reference panel. For each SNP, the effect size (β), standard error, and p-value were extracted, and F-statistics were calculated to assess instrument strength (F > 10 considered adequate). The proportion of variance explained (R2) was computed using standard formulas for continuous exposures. For each instrument, we recorded the effect allele and effect on olive oil use (βexposure), standard error, and p-value. We also calculated the proportion of variance in the exposure explained (R2) and the Fstatistic for each SNP to evaluate instrument strength. The resulting instrument set consisted of 9 independent SNPs associated with olive oil use at P < 5×10-6. All 9 SNPs had F-statistics > 10 (range from 23 to 27), indicating they are sufficiently strong instruments to minimize weak instrument bias. Supplementary Table 1 lists the SNP IDs, their olive oil association statistics, and F-statistics. Notably, none of these SNPs are located in or near the APOE gene region on chromosome 19 (the nearest genome-wide hits for olive oil were on other chromosomes), which reduces concern that our instruments could proxy APOE ε4 status. For the outcome, we obtained genetic association estimates for Alzheimer’s disease from the largest available GWAS meta-analysis of AD. We used summary statistics corresponding to GWAS ID ieu-b-5067 from the IEU OpenGWAS database, which corresponds to a 2022 metaanalysis of late-onset AD. This dataset includes 488,285 individuals of European ancestry (combining several cohorts), with roughly 71,880 clinically diagnosed AD cases and the remainder controls or proxy-cases [17]. The majority of cases came from the IGAP consortium and UK Biobank (using parental dementia history as proxy cases), as reported by Jansen et al. (2019) and updated by later analyses [18]. The AD GWAS was not conditioned on APOE genotype (i.e. the strong effect of APOE ε4 is present in the summary data), and results were reported as log-odds ratios (log OR) for AD per effect allele. We checked that none of the 9 olive oil instrument SNPs were palindromic with intermediate allele frequencies or had mismatched alleles between the exposure and outcome datasets. In initial design, if any issues had arisen, we planned to harmonize alleles and exclude ambiguous variants. In the end, all 9 SNPs were available in the AD GWAS and could be harmonized unambiguously.

Mendelian randomization

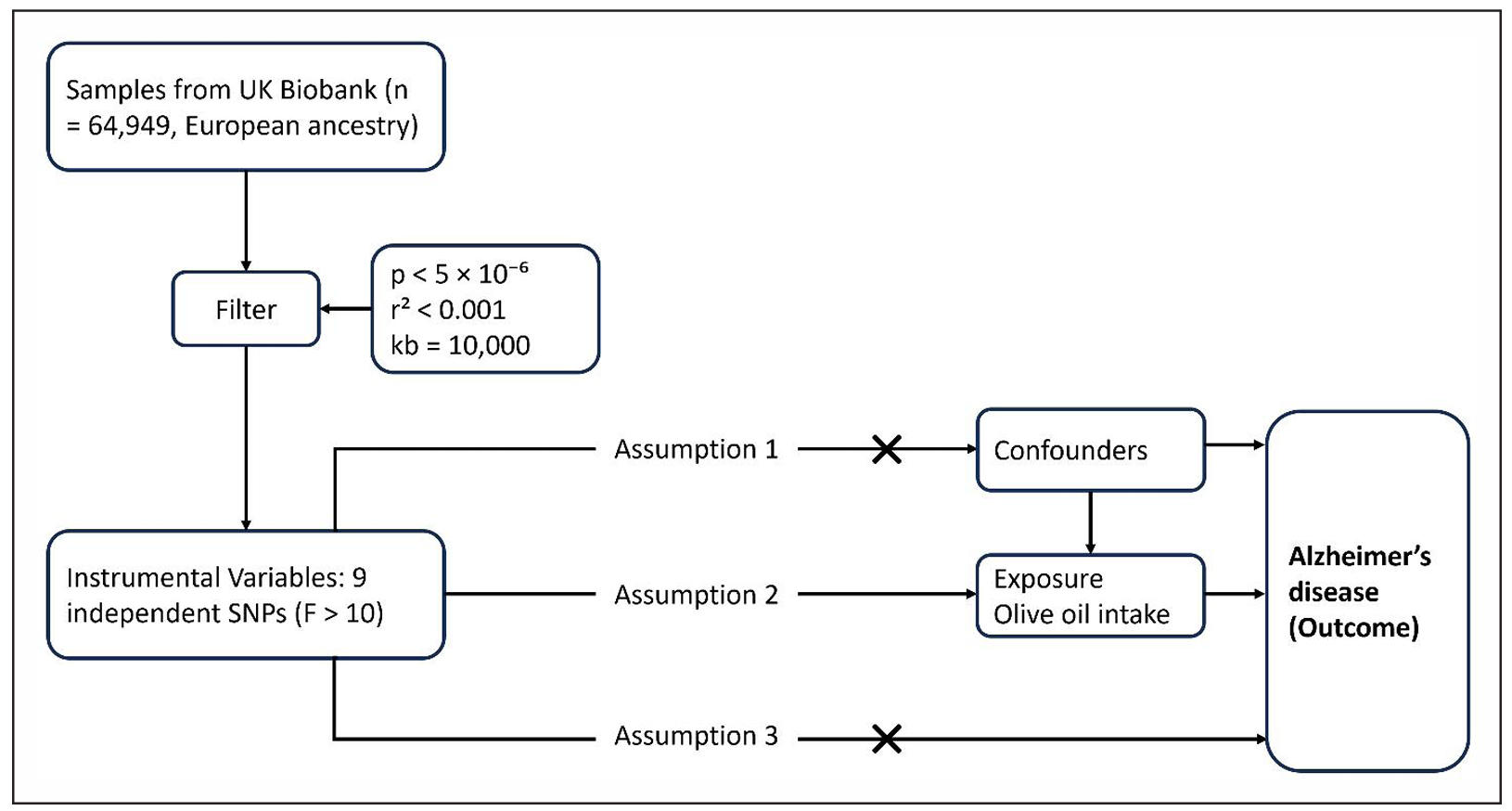

The primary MR analysis was carried out using the inverse-variance weighted (IVW) method under a randomeffects model (Figure 1), with SNP-specific weights proportional to the inverse of the squared standard error of their outcome association. Statistical significance was defined as two-sided P < 0.05, and results were expressed as β coefficients and odds ratios (OR = eβ) per 1 SD increase in genetically predicted olive oil consumption. The IVW estimate can be interpreted as the weighted regression slope of SNP-AD associations on SNP-olive associations, representing the causal log OR for AD per unit increase in olive oil consumption, assuming all SNPs are valid instruments. A fixed-effect IVW was also calculated given the relatively small number of instruments, but since there was no evidence of heterogeneity, the randomand fixedeffect estimates were nearly identical. We exponentiated the log OR to obtain an odds ratio (OR) for interpretability. The statistical significance threshold was set at P < 0.05 for the main IVW analysis, as we tested a single primary hypothesis.

Figure 1. Conceptual framework for the primary Mendelian randomization (MR) analysis. Genetic variants associated with olive oil intake (instrumental variables) are used as proxies for the exposure.

To assess the robustness of the result, we implemented several sensitivity MR methods that relax the standard IVW assumptions. MR-Egger regression provides an estimate of the causal effect while allowing for an intercept term that captures average directional pleiotropy. The MREgger point estimate and its 95% confidence interval were computed. More importantly, the MR-Egger intercept for deviation from zero was tested. A non-zero intercept (with P < 0.05) would indicate overall horizontal pleiotropy among the instruments, whereas a non-significant intercept suggests no strong directional pleiotropy [19]. Weighted median MR was also performed, which could yield a consistent causal estimate even if up to 50% of the weight comes from invalid instruments, as reported previously [20]. Additionally, mode-based estimates (simple and weighted) were explored, which group SNPs by the similarity of their causal effects and derive the overall effect from the largest cluster, providing consistency under different patterns of invalid instruments [21].

Pleiotropy and heterogeneity diagnostics

Heterogeneity in the SNP effect estimates was evaluated using Cochran’s Q statistic for IVW and for MR-Egger. Cochran’s Q assesses whether there is greater dispersion in individual SNP causal estimates than expected by chance; a high Q (with P < 0.05) would suggest that effect sizes differ beyond sampling error, potentially due to heterogeneity or outliers. If significant heterogeneity were found, we planned to report the random-effects IVW result (which accounts for between-SNP variance) and investigate outliers. We also constructed a funnel plot of each SNP’s MR estimate (βSNP = βAD/βolive) against its precision; symmetry of the funnel indicates no small-study or directional bias. MR-PRESSO global test was run to detect any outlier SNPs with pleiotropic distortion; if MRPRESSO identified outliers, we intended to repeat IVW after removing them [22]. Furthermore, a leave-one-out analysis was conducted by re-computing the IVW estimate 9 times, each leaving one SNP out.

Two-step Mendelian randomization mediation analyses

We hypothesized that any causal effect of olive oil on AD might operate via cardiovascular or metabolic improvements (since olive oil is known to improve lipid profiles, reduce blood pressure, etc., which in turn might influence dementia risk). To test this, we performed two-step MR for multiple mediators: six lipid traits (low-density lipoprotein cholesterol, high-density lipoprotein cholesterol, total cholesterol, triglycerides, apolipoprotein B, apolipoprotein A1), two blood pressure traits (systolic and diastolic blood pressure), two stroke subtypes (ischemic stroke overall, and the small-vessel stroke subtype, as AD could be influenced by cerebrovascular disease), three metabolic traits (body mass index, waist-hip ratio adjusted for BMI, and type 2 diabetes mellitus), and one inflammation marker (C-reactive protein, CRP). These mediators were chosen a priori to represent major pathways of interest: lipid-related, vascular, metabolic, and inflammatory pathways. For each putative mediator, we obtained genetic association estimates for that mediator from corresponding GWAS (all largely European ancestry, taken from IEU OpenGWAS or published sources).

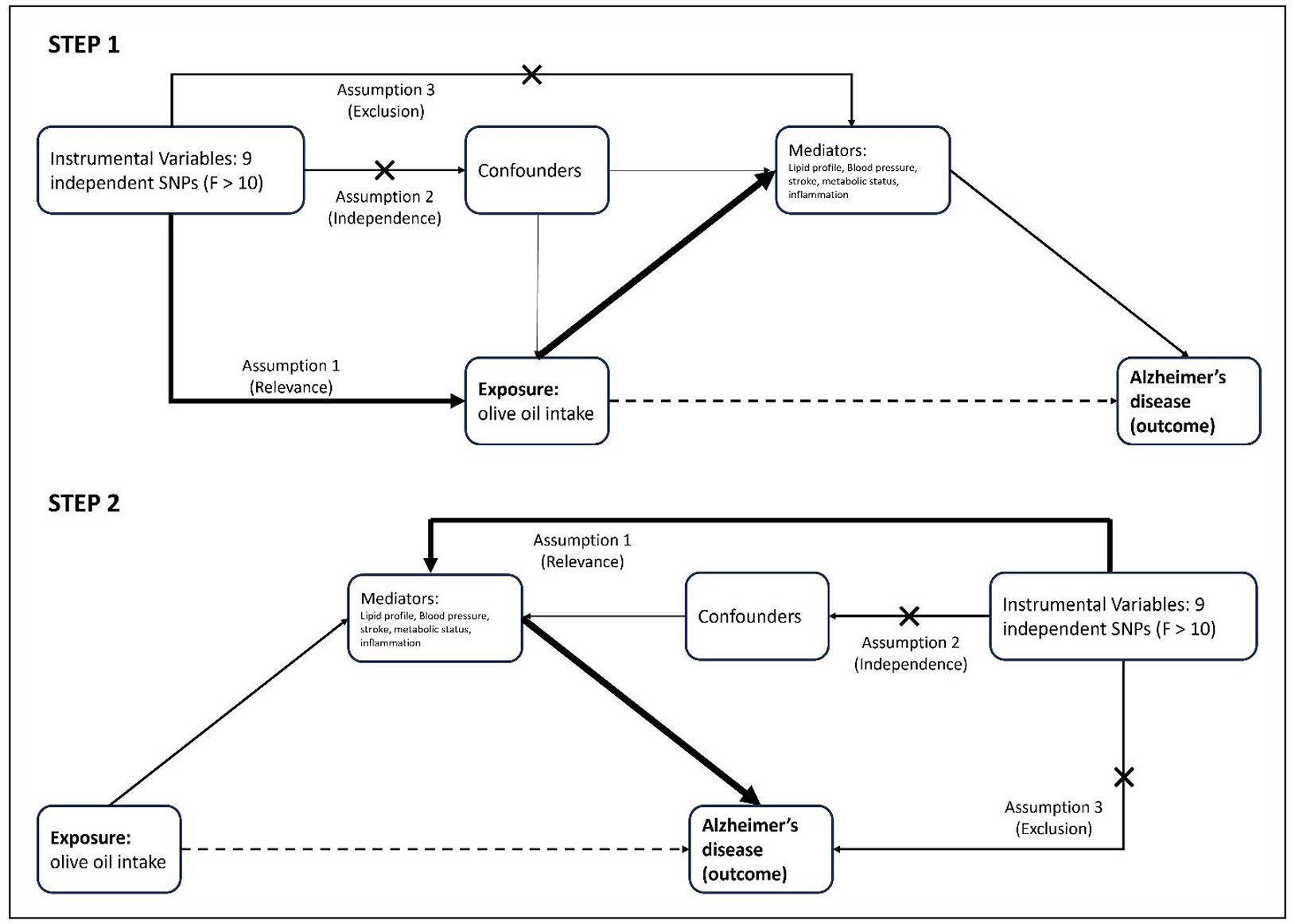

We then carried out two MR analyses: (a) olive-oil → mediator, using our 9 olive SNPs against the mediator outcome; and (b) mediator → AD, using SNPs associated with the mediator as instruments against AD risk. The framework for the two-step MR performed in this study is presented in Figure 2. Where possible, we used the same SNPs for both steps (i.e., if a SNP was a valid instrument for both olive and mediator), or else separate instrument sets were used and combined via the product method. The indirect effect of olive oil on AD via a given mediator was calculated as the product of the MR estimate for olive oil on the mediator and the estimate for the mediator on AD. Standard errors for indirect effects were derived using the delta method, and Z-tests were used to assess the significance of mediation. We also estimated the proportion of the total effect mediated, although given the total effect was close to 0, this proportion is not meaningful in practice. The two-step MR analyses were implemented for each mediator separately; a Bonferroni correction could be applied within each category if needed, but since none approached significance, we report unadjusted p-values for clarity.

Figure 2. Two-step MR framework (olive oil → AD). Step 1: Olive-oil SNP instruments estimate the effect olive intake → mediator (β1). Step 2: Mediator-specific SNP instruments estimate mediator → Alzheimer’s disease (β2). Mediators tested were six lipid traits (LDL-C, HDL-C, TC, TG, ApoB, ApoA1), two blood-pressure traits (SBP, DBP), two stroke subtypes (ischemic stroke, small-vessel stroke), three metabolic traits (BMI, WHRadjBMI, T2D), and CRP.

Multivariable Mendelian randomization

While two-step MR evaluates potential mediating pathways separately, multivariable Mendelian randomization (MVMR) allows assessment of the direct effect of olive oil consumption while simultaneously controlling for multiple correlated risk factors. We included four traits that could lie on the causal pathway: apolipoprotein B (ApoB), systolic blood pressure (SBP), diastolic blood pressure (DBP), body mass index (BMI), and C-reactive protein (CRP). These were chosen because olive oil intake in observational studies is linked to improved lipid profiles, lower blood pressure, and reduced inflammation, all recognized midlife risk factors for dementia. SNP instruments for ApoB, SBP, BMI, and CRP were obtained from large published GWAS (> 250,000 samples each) and combined with olive oil SNPs after clumping (r2 < 0.001; 10,000 kb) to ensure independence. Genetic associations for each SNP with all exposures and with Alzheimer’s disease were harmonized. Multivariable IVW regression was then applied to estimate the direct causal effects of each exposure on AD, accounting for correlations between instruments [23]. The model used inverse-variance weighting and was fitted in R (version 4.2.2) using the TwoSampleMR and MVMR packages [24, 25]. Conditional Fstatistics were used to assess instrument strength, and all tests were two-sided with significance set at P < 0.05. Analyses followed the STROBE-MR reporting guidelines, and no multiple comparison adjustment was applied to the primary hypothesis (olive oil association with AD).

Results

Genetic instruments for olive oil consumption

We identified 9 independent SNPs associated with olive oil use in UK Biobank at P < 5 × 10-6 (none reached the conventional 5 × 10-8 threshold). The lead variants were located in several loci across the genome (on chromosomes 1, 3, 5, 7, 8, 9, 10, and 11, Supplementary Table 1). The strongest instrument was rs6966854 on chromosome 7 (P = 2.2 × 10-7 for association with olive oil use), and all 9 SNPs had P < 5 × 10-6 by design. The effect sizes for these SNPs on the olive oil phenotype were small (e.g. > the largest β was 0.055 on an SD scale), reflecting the polygenic and weakly heritable nature of dietary preferences. Cumulatively, the 9 SNPs explained an estimated R2 of 0.074% of the variance in olive oil use. The mean F-statistic was 24, with each SNP having F > 10, indicating that the genetic instrument collectively had sufficient strength for MR (reducing risk of weak-instrument bias towards the null). None of the SNPs showed genome-wide associations with obvious confounders (we cross-checked against known trait associations in GWAS Catalog), though a few were in or near genes of interest (for example, one SNP near ANKRD55 has been associated with autoimmune conditions, and another near KLF10 related to metabolic traits). Palindromic variants were aligned by allele frequency, and there were no ambiguities in harmonization.

Primary analysis of olive oil and Alzheimer’s disease

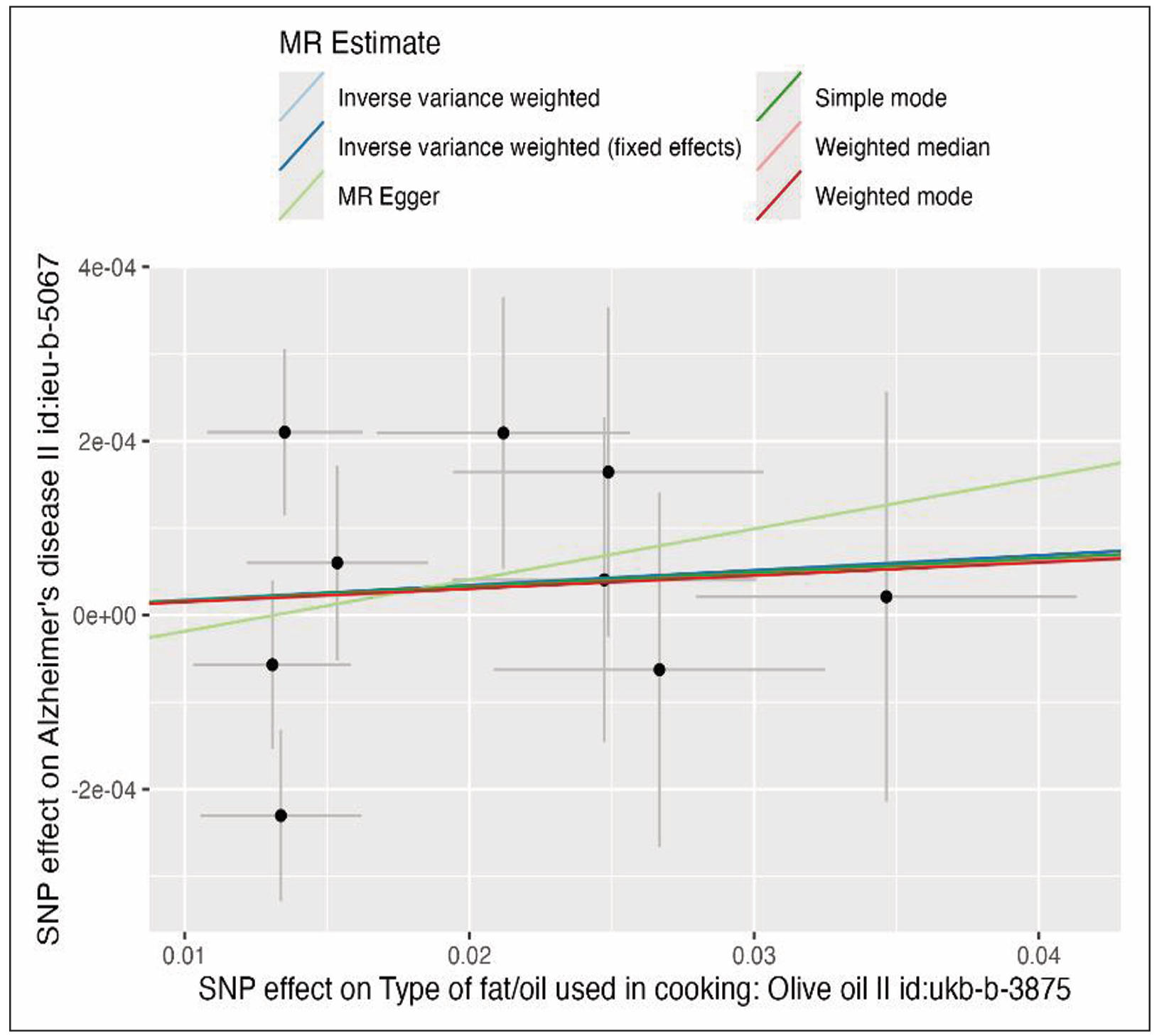

The IVW MR analysis revealed no evidence of a causal effect of olive oil consumption on Alzheimer’s disease risk (Figure 3). The scatter plot shows that all nine genetic instruments cluster tightly around the null effect line. The regression slopes for IVW, MR-Egger, weighted median, and mode-based estimators are nearly flat and overlapping, indicating consistency across methods. The narrow dispersion of SNP estimates around the origin suggests no outlier variants with disproportionately large effects, reinforcing the robustness of the null finding.

Figure 3. Scatter plot of SNP associations with olive oil consumption (x-axis) and Alzheimer’s disease risk (y-axis). Regression lines represent causal estimates from inverse variance weighted (IVW), MR-Egger, weighted median, and mode-based methods.

The IVW estimate (random-effects) was a log OR of 0.0017 (95% CI: -0.0045 to 0.0079) per SD increase in olive oil consumption (Table 1). This corresponds to an OR of 1.0017 (approximately 1.002) for AD per SD higher olive oil use, with a 95% confidence interval ranging from 0.9955 to 1.0079. The association was not statistically significant (P = 0.583). Using a fixed-effects IVW model (appropriate given low heterogeneity), the estimate was identical (β = 0.0017) with a slightly smaller standard error (SE = 0.0024) and P = 0.48. For interpretation, an SD increase in the olive oil usage phenotype (which might be akin to comparing people who primarily use olive oil versus those who rarely do) was associated with essentially no change in AD risk. The point estimate was very close to zero, and the confidence intervals excluded any effect of material importance. For instance, we can infer that a protective effect larger than roughly 1% reduction in odds of AD per SD of olive oil use is statistically incompatible with our data (since the 95% CI lower bound was OR 0.995). Similarly, there was no evidence of a harmful effect (upper CI: 1.008, just a 0.8% possible increase) (Table 1).

Table 1.

Mendelian randomization estimates of olive oil intake on Alzheimer’s disease.

| Method | SNPs | β (SE) | P-value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Inverse variance weighted (random) | 9 | 0.0017 (0.0031) | 0.58 |

| Inverse variance weighted (fixed) | 9 | 0.0017 (0.0024) | 0.48 |

| MR egger | 9 | 0.0059 (0.0105) | 0.59 |

| Weighted median | 9 | 0.0016 (0.0035) | 0.65 |

| Simple mode | 9 | 0.0016 (0.0054) | 0.77 |

| Weighted mode | 9 | 0.0015 (0.0050) | 0.77 |

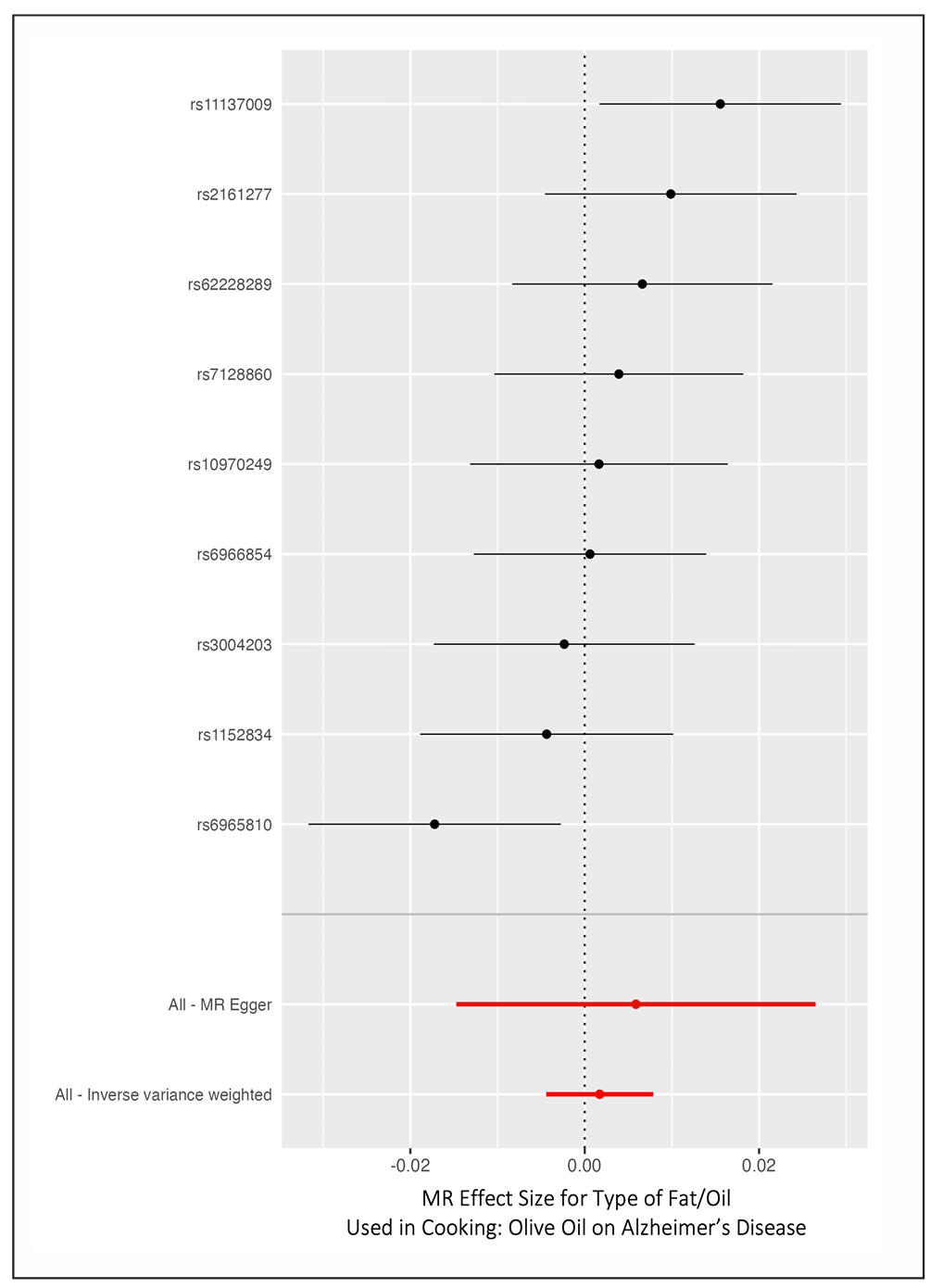

All sensitivity MR methods concurred with the null finding (Figure 4). The forest plot illustrates individual SNP effects on Alzheimer’s disease risk, along with pooled estimates from IVW and MR-Egger. Each SNP-specific estimate is centered close to zero, with 95% confidence intervals overlapping the null. The combined IVW and MR-Egger estimates are similarly centered around the null line, demonstrating that neither individual instruments nor aggregate estimates provide evidence for a causal association. This uniformity across SNPs rules out the possibility that a subset of instruments might be driving the results.

Figure 4. Forest plot displaying SNP specific Wald ratio estimates and overall Mendelian randomisation est-imates (IVW and MR-Egger) for olive oil consumption on Alzheimer’s disease risk. Confidence intervals crossing the null line indicate non-significance.

MR-Egger regression yielded a causal estimate of β = 0.0059 (SE 0.0105), which, although positive in point estimate, was not significantly different from zero (P = 0.59). The MR-Egger point estimate has a wide CI (-0.0148 to 0.0266 on the log OR scale), but it overlaps with the IVW estimate. Importantly, the MR-Egger intercept was -0.00008 (SE 0.00019), which is very close to zero with P = 0.689. This indicates no evidence of directional pleiotropy on average, the genetic instruments do not appear to influence AD through pathways unrelated to olive oil (if they did, the intercept would likely deviate from zero). The intercept CI (-0.00045 to 0.00029) is narrow, suggesting any net pleiotropic effect is negligible. Weighted median MR gave an estimate of β = 0.0016 (SE 0.00345, P = 0.648), virtually identical to IVW. Simple mode and weighted mode estimates were also near zero (β ≈ 0.0015) and non-significant (P > 0.76). Thus, whether we assume that at least 50% of the weight comes from valid instruments (weighted median) or even that only the largest instrument cluster is valid (mode methods), the conclusion remains the same: no causal effect of olive oil on AD. Table 1 summarizes the MR estimates by method, all of which are null.

Pleiotropy and heterogeneity checks

We found no significant heterogeneity in the SNP-specific causal estimates. Cochran’s Q for IVW was Q = 13.11 on 8 degrees of freedom (P = 0.108), indicating that the variation in SNP effects could be due to chance alone. For MR-Egger, Q = 12.79 on 7 df > (P = 0.077); while slightly lower df >, this was also non-significant (and the borderline P = 0.077 likely reflects one less SNP or inherent noise rather than definite heterogeneity). Given the nonsignificant Q, we interpret that the instruments are fairly homogeneous in their estimated effect on AD which strengthens the validity of the IVW estimate. The scatterplot visually confirms that all SNPs cluster tightly around the null line, with no outliers far off the regression line (Figure 3).

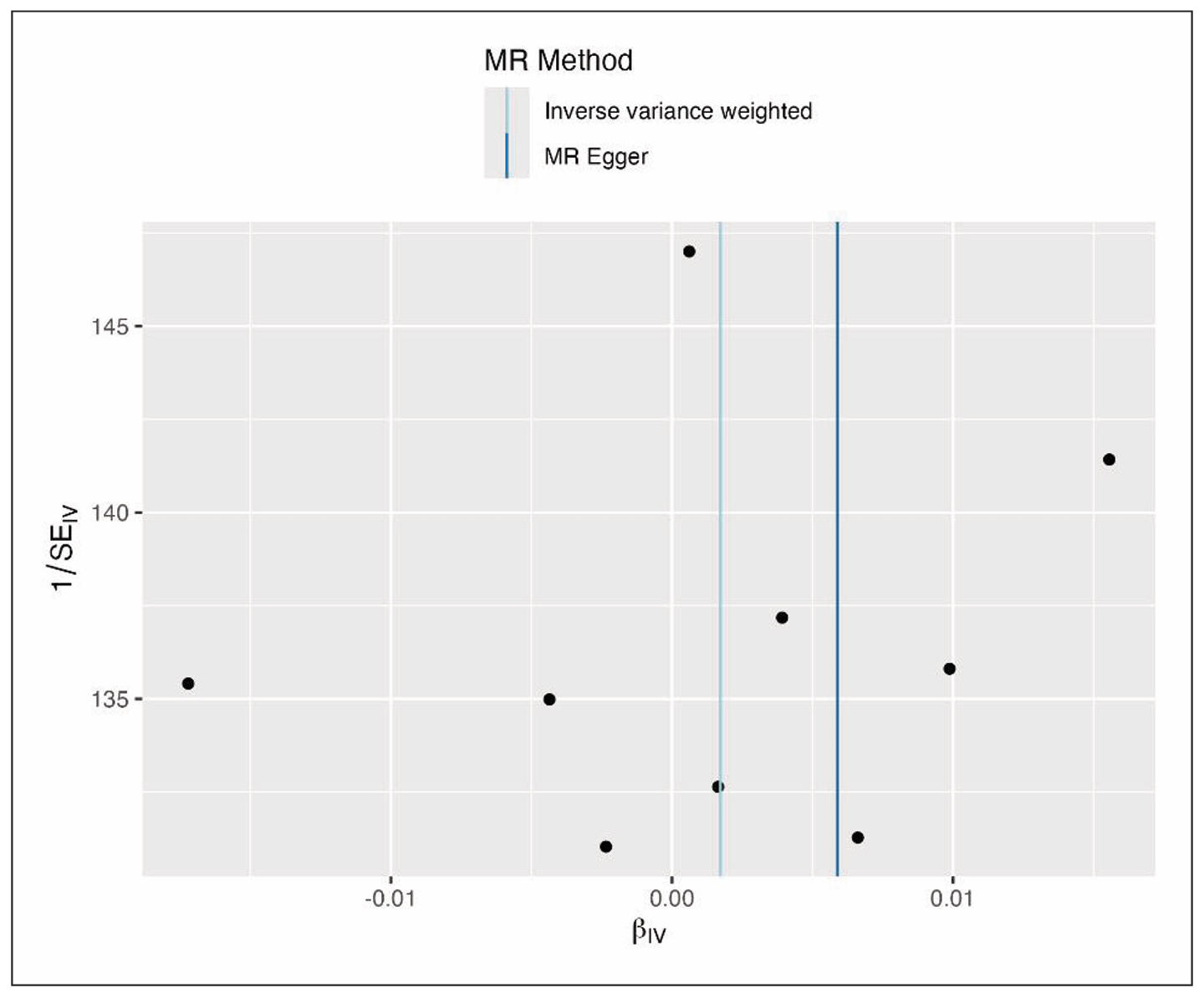

The funnel plot (Figure 5) of SNP effects was symmetric and roughly inverted funnel-shaped, as expected under no directional pleiotropy. The funnel plot displays SNP estimates plotted against their precision. The distribution is symmetric around the vertical null line, indicating the absence of systematic bias. SNPs with higher standard errors (less precise estimates) scatter more widely, as expected, but remain evenly balanced across both sides of the null. The lack of skewness in the funnel supports the conclusion from MR-Egger’s intercept test that there is no directional pleiotropy, confirming that genetic instruments are valid.

Figure 5. Funnel plot of SNP-specific causal estimates for olive oil consumption and Alzheimer’s disease. Symmetry of the plot suggests no evidence of directional pleiotropy.

SNPs with larger SE (less precise) showed wider scatter around the zero effect, but there was no tendency for those to lean to one side of the null. The MR-Egger intercept test, as noted, was null (P = 0.69), reinforcing that there is no evidence that the instruments as a group have pleiotropic biases. We also applied the MR-PRESSO global test, which did not detect any outlier SNP (global test P = 0.72). Therefore, we did not remove any SNPs as potential pleiotropic outliers all instruments were retained in the analysis.

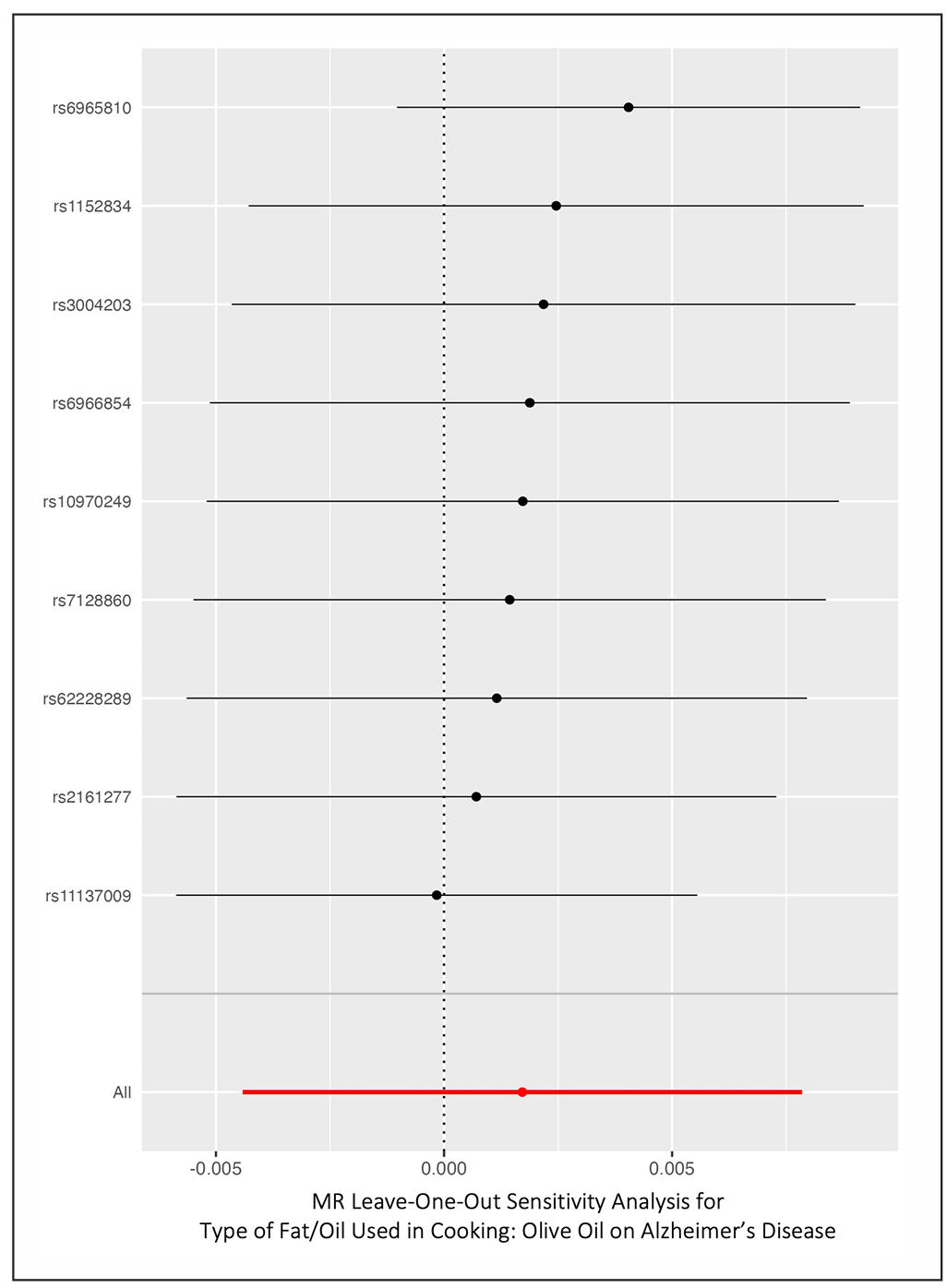

The leave-one-out sensitivity analysis further demonstrated the robustness of the null result (Figure 6). The leaveone-out analysis demonstrates that removing any single SNP does not materially alter the overall causal estimate. Each recalculated IVW estimate lies close to zero, with confidence intervals consistently spanning the null. This stability across all iterations indicates that no single SNP exerts undue influence on the analysis. Such robustness enhances confidence that the null finding is not driven by outlier variants or instrument instability.

Figure 6. Leave-one-out sensitivity analysis of the causal effect of olive oil consumption on Alzheimer’s disease. Each point shows the IVW estimate after excluding one SNP at a time; all estimates remain close to the null.

When excluding each SNP in turn, the IVW estimates remained very close to zero and none of those excludingone analyses yielded a significant association. For instance, leaving out the top SNP on chr7 (rs6966854) gave an OR of 1.0017 (P = 0.63); leaving out rs11137009 (chr8) gave OR: 0.9998 (P = 0.96); leaving out rs10970249 (chr9) gave OR: 1.0025 (P = 0.47); and so on (full leaveone-out results in Supplementary Table 2). No single variant’s removal produced a notable swing in effect size or confidence interval. We also note that none of the individual SNP-AD associations showed even a nominally significant effect on AD (all single-SNP Wald ratios had P > 0.4).

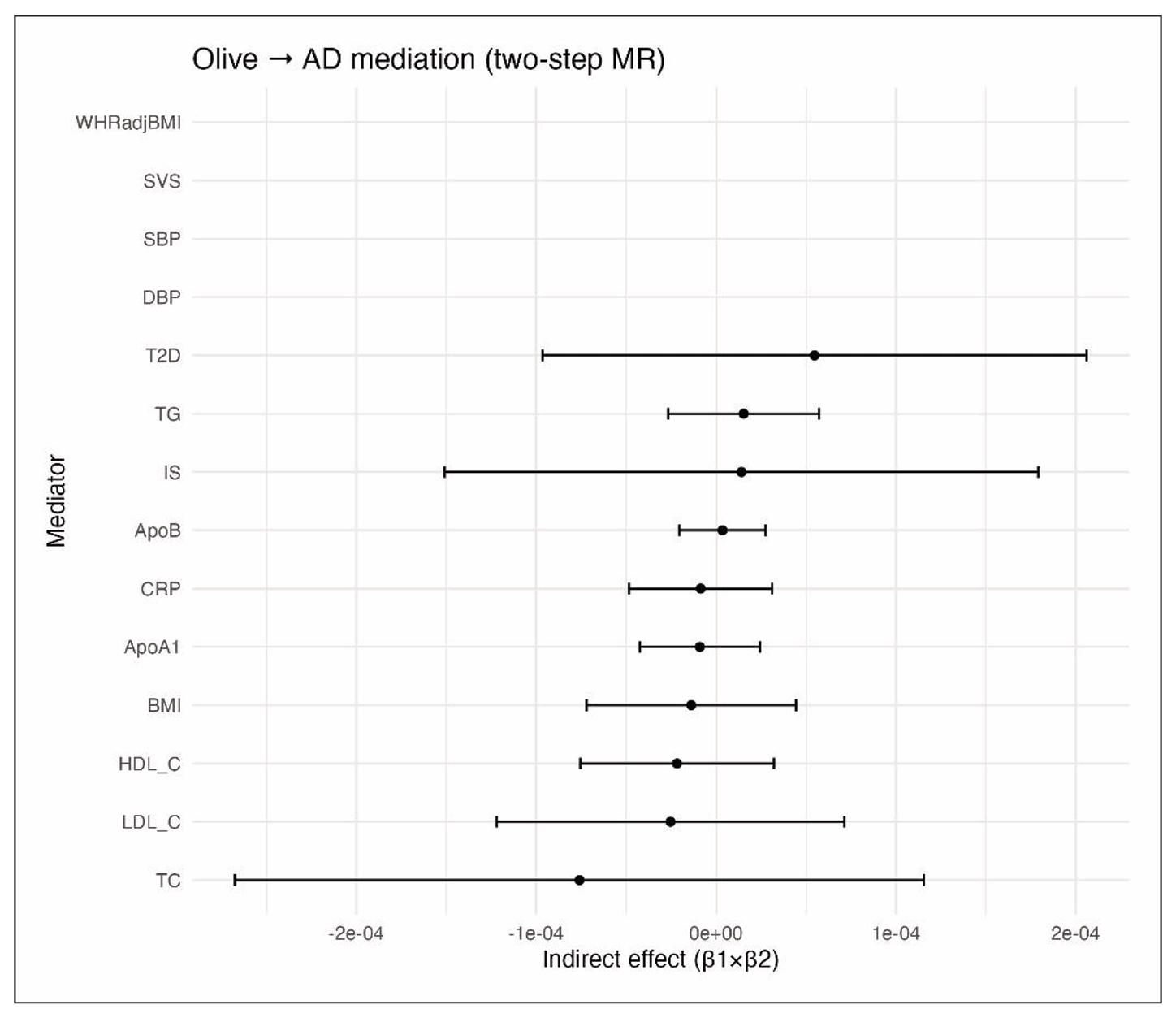

Two-step Mendelian randomization results

Given the null total effect of olive oil on AD, the mediation analyses also yielded null results. The two-step MR provided no significant indirect effects through any tested pathway, but the estimates still help clarify where an effect would have appeared if present (Table 2). For lipid traits, genetic proxies for olive oil showed no meaningful association with circulating lipids. For LDL-C, the IVW estimate for olive oil to LDL-C was β = +0.055 SD per SD of olive oil (95% CI -0.137 to +0.248, P = 0.58). Associations were likewise non-significant for HDL (β = +0.083, P = 0.24), triglycerides (β = -0.046, P = 0.38), total cholesterol (β = +0.0313, P = 0.14), apolipoprotein B (β = -0.046, P = 0.75), and apolipoprotein A1 (β = +0.059, P = 0.32). MR estimates for lipid traits to AD were mostly null as well: LDL-C β = -0.00046 per SD (P = 0.18), HDL-C β = -0.00026 (P = 0.28), triglycerides β = -0.00033 (P = 0.22), and ApoB β = -0.00020 (P = 0.48).

Table 2.

Two-step mediation analysis of olive oil intake on AD via metabolic traits.

| Mediator | (Olive oil → Mediator) (SE) | P (Olive oil → Mediator) | β (Mediator → AD) (SE) | P (Mediator → AD) | Indirect β (SE) | z | P (Indirect) | Prop. mediated |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| LDL-C | 0.055 (0.098) | 0.58 | –0.00046 (0.00035) | 0.18 | 2.5×10- 5 (4.9×10- 5) | –0.51 | 0.61 | -0.015 |

| HDL-C | 0.083 (0.071) | 0.24 | –0.00026 (0.00024) | 0.28 | –2.2×10- 5 (2.7×10- 5) | –0.79 | 0.43 | –0.015 |

| TG | –0.046 (0.052) | 0.38 | –0.00033 (0.00027) | 0.22 | 1.5×10- 5 (2.2×10- 5) | 0.71 | 0.48 | –0.015 |

| TC | 0.313 (0.213) | 0.14 | –0.00024 (0.00027) | 0.36 | –7.6×10- 5 (9.8×10- 5) | –0.78 | 0.44 | –0.015 |

| ApoB | –0.017 (0.055) | 0.75 | –0.00020 (0.00029) | 0.48 | 3.5×10- 6 (1.2×10- 5) | 0.29 | 0.77 | –0.015 |

| ApoA1 | 0.059 (0.060) | 0.32 | –0.00015 (0.00024) | 0.53 | –9.0×10- 6 (1.7×10- 5) | –0.53 | 0.59 | –0.015 |

| SBP | NA | NA | 0.00002 (0.00050) | 0.97 | NA | NA | NA | –0.015 |

| DBP | NA | NA | –0.00031 (0.00048) | 0.51 | NA | NA | NA | –0.015 |

| T2D | 0.251 (0.304) | 0.41 | 0.00022 (0.00016) | 0.16 | 5.5×10- 5 (7.7×10- 5) | 0.71 | 0.48 | –0.015 |

| BMI | –0.049 (0.078) | 0.53 | 0.00028 (0.00041) | 0.49 | –1.4×10- 5 (3.0×10- 5) | –0.46 | 0.64 | –0.015 |

| WHRadjBMI | 0.165 (0.241) | 0.49 | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | –0.015 |

| IS | –0.146 (0.251) | 0.56 | –0.00010 (0.00055) | 0.86 | 1.4×10- 5 (8.4×10- 5) | 0.17 | 0.87 | –0.015 |

| SVS | 1.041 (0.707) | 0.14 | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | –0.015 |

| CRP | 0.027 (0.056) | 0.63 | –0.00032 (0.00035) | 0.36 | –8.6×10- 6 (2.0×10- 5) | –0.42 | 0.67 | –0.015 |

Note: NA, not applicable because either the olive oil → mediator or mediator → AD association could not be estimated with sufficient instruments

Because neither step was significant, indirect effects were essentially zero, for example LDL-mediated βindirect = 0.055 × (-0.00046) = -0.000025 with P = 0.61. Results were similar for HDL, triglycerides, total cholesterol, ApoB, and ApoA1 (all P > 0.4). These findings do not support lipid-mediated pathways.

Genetically higher blood pressure showed only weak, non-significant links to AD in this dataset; for example, a 10 mmHg higher SBP corresponded to an OR of 1.00 for AD with P = 0.97. Accordingly, indirect effects via SBP or diastolic blood pressure were non-significant (both P > 0.9). Using large stroke GWAS instruments, olive oil genetic scores were not associated with ischemic stroke risk (P = 0.56), and stroke liability did not show a significant effect on AD (P = 0.86). Small-vessel stroke behaved similarly. No mediation through blood pressure or stroke was detected.

For metabolic traits, genetically higher olive oil use did not reduce adiposity or diabetes risk. The point estimate for BMI was positive and non-significant (P = 0.53). Waist-hip ratio adjusted for BMI showed no association (β = -0.002 SD, P = 0.98), and type 2 diabetes liability was also null (OR: 1.03 per SD of olive oil, P = 0.41). In mediator-to-outcome analyses, higher genetically predicted BMI showed a small, non-significant inverse relation with AD (P = 0.49), and type 2 diabetes liability had no significant effect (P = 0.16). Indirect effects of olive oil via BMI and diabetes were not significant (P = 0.64 and 0.48). There is therefore no evidence for mediation through metabolic pathways. For inflammation, CRP did not appear to mediate any effect. Olive oil instruments were not associated with CRP (β = +0.027 SD of log-CRP per SD of olive oil, P = 0.63), and CRP showed no causal effect on AD (β = -0.00032 per SD, P = 0.36). The indirect effect via CRP was non-significant (P = 0.67).

Overall, across lipid, vascular, metabolic, and inflammatory domains, two-step MR showed no significant mediation (Figure 7). Neither the cardiometabolic effects often attributed to olive oil nor potential adverse metabolic effects translated into any detectable change in AD risk within the precision of this analysis. The analysis shows that genetically predicted olive oil consumption does not significantly alter lipid traits (LDL, HDL, triglycerides, ApoB, ApoA1), blood pressure (systolic, diastolic), metabolic traits (BMI, WHR, type 2 diabetes), or inflammation (C-reactive protein). Furthermore, none of these traits exhibit a significant causal relationship with AD in this dataset. Consequently, all indirect effect estimates are close to zero, with wide confidence intervals encompassing null.

Figure 7. Two-step Mendelian randomization analysis testing mediation pathways between olive oil consumption and Alzheimer’s disease. Pathways assessed include lipid traits, blood pressure, metabolic risk factors, and systemic inflammation. No significant indirect effects were observed.

Multivariable Mendelian randomization results

A multivariable MR was performed including olive oil and four risk factors (ApoB, SBP, BMI, CRP) to estimate the direct effect of each on AD, where the results are presented in Table 3. The direct effect of olive oil on AD, controlling for those factors, was null. The multivariable IVW yielded a coefficient β = -0.00244 for olive oil (SE = 0.00241), corresponding to OR of 0.9976 per SD increase in olive oil use, with P = 0.31.

Table 3.

Multivariable MR estimates.

| Exposure | SNPs | β (SE) | P-value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Body mass index | 21 | –0.00036 (0.00073) | 0.62 |

| Systolic blood pressure | 98 | 0.00040 (0.00056) | 0.48 |

| C-reactive protein | 22 | –0.00078 (0.00071) | 0.27 |

| Apolipoprotein B | 28 | –0.00037 (0.00035) | 0.29 |

| Olive oil intake | 0* | –0.00244(0.00241) | 0.31 |

Note: * means no valid instruments remained after conditioning on covariates.

The MVMR estimates for other exposures also did not reach a statistical significance. For ApoB, the direct effect was β = -0.00037 (SE = 0.00035) on AD (OR: 0.9996 per 1 SD increase), P = 0.29. SBP showed β = +0.00040 (SE = 0.00056) per SD increase (5 mmHg), P = 0.48. BMI had β = -0.00036 (SE = 0.00073) per SD increase (4.8 kg/ m2), P = 0.62. CRP had β = -0.00078 (SE = 0.00071) per SD increase, P = 0.27. None of these associations reached significance. In the multivariable analysis, olive oil also did not demonstrate a significant direct effect on AD. The point estimate was close to null (OR:1.00), with a 95% CI ranging approximately from 0.993 to 1.002. The MVMR models accounted for overlapping instruments across exposures, and the confidence intervals, although wider than in univariable MR, still excluded moderate effects.

Discussion

In this two-sample MR study, we found no evidence that genetically predicted olive oil consumption reduces the risk of Alzheimer’s disease. Despite olive oil’s reputed health benefits and observational links to better cognitive health, our MR results indicate that any causal impact on AD is likely negligible. The IVW MR estimate was essentially null (OR: 1.00, P = 0.58), and a variety of sensitivity analyses (MR-Egger, median, mode) all concurred, with no hint of a protective effect. There was no sign of confounding by pleiotropy. The MR-Egger intercept was nearly zero (P = 0.69) and the funnel plot was symmetric, suggesting the genetic instruments were valid proxies for the exposure. Furthermore, we undertook extensive investigations to see if olive oil might influence AD indirectly via improving cardiovascular or metabolic risk factors. These two-step MR mediation analyses consistently came up null: olive oil genetic proxies did not significantly affect lipid levels, blood pressure, adiposity, or inflammation in our data, nor were those factors strongly causally related to AD in a way that would imply mediation. The multivariable MR analysis, accounting jointly for olive oil and major risk factors, confirmed that when controlling for those pathways, olive oil still had no observable effect on AD risk. Overall, the evidence from our study is consistent with a true null causal relationship between olive oil intake and Alzheimer’s disease.

This finding contrasts with some observational epidemiological studies that have suggested a beneficial link between olive oil (or Mediterranean diet patterns) and lower dementia risk. For example, the cohort study by Scarmeas et al. found a ~40% lower AD risk in individuals with high Mediterranean diet adherence (with olive oil as a key component) [2]. More recently, a large analysis of U.S. cohorts reported that people consuming > 7 g/day of olive oil had 28% lower risk of dying due to dementia compared to those rarely consuming olive oil [10]. Additionally, a cohort and RCT in Spanish population revealed that the Mediterranean diet with olive oil was associated with better cognitive outcomes than a low-fat diet, but the effect was observed after adjusting with major cardiovascular risk factors [7, 8]. Pooled estimates of multiple observational studies revealed that Mediterranian diet is significantly associated with reduced AD, but high heterogeneity cannot be ignored [26].

One likely explanation is confounding and healthy-user bias in observational studies. Olive oil consumption is a hallmark of a healthier dietary pattern and lifestyle. In Western populations (like the U.S. cohorts), individuals who use olive oil tend to also have higher education, higher income, healthier overall diets (more vegetables, fish, less saturated fat), and better access to healthcare–all factors linked to lower dementia risk. The U.S. study attempted to adjust for diet quality and even APOE genotype and still found an association, but residual confounding is hard to eliminate entirely [10]. MR, by using genetic variants as proxies, is not influenced by these sociobehavioral confounders. Our null result suggests that those observational associations might not be due to olive oil itself, but rather due to other correlated factors. Supporting this, when diet quality was accounted for, olive oil was still associated with less dementia mortality in that study, but MR finds the genetic inclination to use olive oil (which should be unrelated to one’s social environment) does not confer an advantage.

Another consideration is reverse causation. Prodromal AD can begin decades before diagnosis and may influence eating habits, especially due to low knowledge and attitude for the disease [27]. For instance, people developing cognitive decline might lose appetite for cooking or switch to simpler diets [28], which could mean less olive oil use if they rely on convenience foods. This could create an illusion that high olive oil intake is protective, whereas in fact, incipient AD leads to dietary changes. MR, using genetic proxies fixed from birth, is immune to reverse causation. Our findings therefore support the absence of a causal effect, whereas longitudinal observational studies may remain vulnerable to confounding by preclinical disease. Similar limitations are also observed in interventional evidence. Two Australian RCTs had only 6 months of followup and dropout exceeding 20% in the intervention arm [29, 30]. Longer RCTs (> 3 years) reported benefits, but their populations had high cardiovascular risk and the intervention combined olive oil with nuts [8, 31], complicating interpretation. A well-designed trial with extended followup in cognitively healthy populations would be required to definitely rule out reverse causation and confounding, but MR provides supportive evidence in the meantime.

It is also instructive to compare our results with MR findings for other dietary factors. A recent comprehensive MR by Teng et al. (2024) screened 231 diet-related traits; they found robust evidence that higher oily fish intake causally reduces AD risk (OR: 0.60, P < 0.001 after FDR correction), whereas olive oil intake did not emerge as significant [32]. They did note suggestive protective signals for some beverages (tea, moderate alcohol) and harmful signals for sugary/fried foods, but olive oil was not noteworthy in that MR scan [32]. Our focused analysis aligns with that broad MR study: olive oil is not a major player in AD causation, whereas fish (rich in omega-3 fatty acids) may be. This suggests that certain components of a Mediterranean diet (like fish or perhaps antioxidants in wine/tea) could be driving the cognitive benefits, rather than olive oil itself.

Our results, herein, are also in line with previous MR studies on plasma lipids and AD which generally do not find a harmful causal effect of higher LDL cholesterol on AD [33, 34]. A study even suggests a paradoxical inverse effect (genetically higher LDL associated with lower AD risk) [33]. Similarly, drug-target MR analyses using variants in HMGCR, APOB, and NPC1L1 showed no evidence that lowering LDL-C through these pathways affects AD risk, though PCSK9 inhibition uniquely appeared to increase AD risk despite its protective effect on coronary artery disease [34]. Given that the primary cardioprotective mechanism of olive oil is thought to operate through lipid modulation, the absence of a causal relationship between lipids and AD risk (and even the possibility of an inverse association) suggests that olive oil is unlikely to influence AD through this pathway. Likewise, although midlife blood pressure is an established risk factor for dementia [35, 36], genetic evidence (including in the present study) indicates only weak causal links between lifelong blood pressure and AD. This may reflect survival bias, whereby individuals with elevated blood pressure who reach older ages possess other protective characteristics, or the mitigating effects of antihypertensive treatment. In this context, our null findings regarding olive oil and AD risk are consistent, where modification of vascular risk factors alone may have limited impact on AD. While vascular dementia or mixed dementia phenotypes may be more responsive to such interventions, our outcome was all-cause AD as captured in genetic datasets, which largely emphasize Alzheimer pathology.

An alternative interpretation is that any potential benefits of olive oil may be context dependent. In the present study, genetic predisposition to olive oil use likely reflects consumption within a predominantly Western dietary context, as the UK Biobank represents a British cohort where olive oil use is less embedded in daily eating habits than in Mediterranean cultures [37, 38]. Under such circumstances, the health effects of olive oil may be attenuated. In contrast, in Mediterranean populations, olive oil is consumed as part of a broader dietary pattern rich in vegetables, legumes, and fish [37]. This pattern provides a combination of neuroprotective nutrients (e.g., vitamins, polyphenols, fiber) while limiting intake of potentially harmful components such as red meat and saturated fat. It is therefore plausible that olive oil in isolation, particularly when incorporated into an otherwise suboptimal diet, exerts little measurable influence on AD risk, whereas the Mediterranean dietary pattern as a whole may be protective through synergistic effects. Mendelian randomization analyses, by design, evaluate olive oil independently and cannot capture the contribution of the broader dietary context. Accordingly, our findings suggest that olive oil alone is unlikely to have a substantial protective effect against AD, without excluding the possibility that adherence to a comprehensive Mediterranean diet confers cognitive benefits.

It is important to acknowledge several limitations when interpreting our findings. First, the genetic instruments for olive oil intake were relatively weak, which reduces statistical power. Although the AD GWAS sample was large (n = ± 488,000), a very small effect might not have been detectable. However, our confidence intervals were narrow (± 0.99–1.01 per SD), suggesting that any true effect is likely negligible (on the order of 1–2% risk reduction). Second, dietary preference phenotypes are inherently complex and may not fully capture true olive oil consumption or its biochemical exposure, introducing potential measurement error. The olive oil exposure phenotype in UK Biobank relied on a single self-report item about usual cooking fat, which lacks dose quantification and may lead to misclassification, biasing results toward the null. While such error is unlikely to correlate with genotype, instrument weakness and reduced precision remain concerns, even though all SNPs exceeded F > 10. Third, our analysis included only individuals of European ancestry, limiting generalizability. Genetic and dietary effects may differ across populations. For example, APOE ε4 prevalence varies globally, and olive oil consumption is generally lower outside Mediterranean regions. Thus, potential effects in populations with lifelong high intake are not directly tested here. Fourth, AD is a heterogeneous outcome in GWAS data, incorporating clinically diagnosed cases and proxy reports. Effects confined to specific dementia subtypes, such as vascular dementia, may be diluted. Our mediation analyses for stroke and small vessel disease found no signal, but subtle domain-specific effects (such as cognitive performance) cannot be excluded.

Conclusions

The present study reveals no causal link between olive oil intake and Alzheimer’s disease. The consistency across MR methods and the lack of effect across multiple pathways strengthen the credibility of this null result. This present MR study adds nuance to the existing literature by showing that, although olive oil is well established as cardioprotective and forms part of dietary patterns linked with healthy aging, it does not appear to provide meaningful protection against Alzheimer’s disease. Nonetheless, adherence to a balanced Mediterranean-style diet, with olive oil as one component, remains advisable for overall health and may reduce dementia risk through other dietary factors and potential synergistic effects. Future work integrating multi-omics data and longitudinal trials will be helpful to fully elucidate the relationship between diet and neurodegeneration.

Declarations

Acknowledgments

This research used data from the UK Biobank and publicly available GWAS consortia. We thank the participants and investigators of these studies for making their data available.

Author contributions

Teuku Fais Duta: conceptualization, methodology, investigation, data curation, visualization, formal analysis, writing original draft. Derren DCH Rampengan: writing original draft. Nuril Farid Abshori: writing original draft. Bryan Gervais de Liyis: validation, writing original draft. Fahrul Nurkolis: validation, supervision, writing review and editing. Muhammad Iqhrammullah: supervision, methodology, conceptualization. All authors have read and agreed to the final version of this manuscript.

Availability of data and materials

The GWAS summary statistics analyzed in this study are publicly accessible through the IEU OpenGWAS platform (https://gwas. mrcieu.ac.uk/) and UK Biobank (https://www.ukbiobank.ac.uk/). All data used are cited within the manuscript and supplementary materials.

Financial support and sponsorship

None.

Conflicts of interest

Not applicable.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Not applicable. This study used publicly available, summary-level genome-wide association study (GWAS) data with no individual-level identifiers.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

References

1. Livingston G, Huntley J, Sommerlad A, Ames D, Ballard C, Banerjee S, et al. Dementia prevention, intervention, and care: 2020 report of the Lancet Commission. Lancet, 2020, 396(10248): 413-446. [Crossref]

2. Scarmeas N, Stern Y, Tang M, Mayeux R, & Luchsinger J. Mediterranean diet and risk for Alzheimer’s disease. Ann Neurol, 2006, 59(6): 912-921. [Crossref]

3. Hersant H, & Grossberg G. The ketogenic diet and Alzheimer’s disease. J Nutr Health Aging, 2022, 26(6): 606-614. [Crossref]

4. Katonova A, Sheardova K, Amlerova J, Angelucci F, & Hort J. Effect of a vegan diet on Alzheimer’s disease. Int J Mol Sci, 2022, 23(23): 14924. [Crossref]

5. Yeung S, Kwan M, & Woo J. Healthy diet for healthy aging.Nutrients, 2021, 13(12): 4310-4321. [Crossref]

6. Fu J, Tan L, Lee J, & Shin S. Association between the mediterranean diet and cognitive health among healthy adults: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Front Nutr, 2022, 9: 946361. [Crossref]

7. Andreu-Reinón M, Chirlaque M, Gavrila D, Amiano P, Mar J, Tainta M, et al. Mediterranean diet and risk of dementia and Alzheimer’s disease in the EPIC-Spain dementia cohort study. Nutrients, 2021, 13(2): 700-712. [Crossref]

8. Valls-Pedret C, Sala-Vila A, Serra-Mir M, Corella D, de la Torre R, Martínez-González M, et al. Mediterranean diet and age-related cognitive decline: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA Intern Med, 2015, 175(7): 1094-1103. [Crossref]

9. Gonçalves M, Vale N, & Silva P. Neuroprotective effects of olive oil: a comprehensive review of antioxidant properties. Antioxidants, 2024, 13(7): 762-775. [Crossref]

10. Tessier A, Cortese M, Yuan C, Bjornevik K, Ascherio A, Wang D, et al. Consumption of olive oil and diet quality and risk of dementia-related death. JAMA Netw Open, 2024, 7(5): e2410021. [Crossref]

11. Nelson A, Pagidipati N, & Bosworth H. Improving medication adherence in cardiovascular disease. Nat Rev Cardiol, 2024, 21(6): 417-429. [Crossref]

12. Sanderson E, Glymour M, Holmes M, Kang H, Morrison J, Munafò M, et al. Mendelian randomization. Nat Rev Methods Primers, 2022, 2, 6. [Crossref]

13. Lovegrove C, Howles S, Furniss D, & Holmes M. Causal inference in health and disease: a review of the principles and applications of Mendelian randomization. J Bone Miner Res, 2024, 39(11): 1539-1552. [Crossref]

14. Chen L, Tubbs J, Liu Z, Thach T, & Sham P. Mendelian randomization: causal inference leveraging genetic data. Psychol Med, 2024, 54(8): 1461-1474. [Crossref]]

15. Wu X, Cheng H, Li C, Li J, Wang L, & Gao H. Olive intake and coronary heart disease: a mendelian randomization study. Cardiology Discovery, 2025, 05(03): 191-201. [Crossref]

16. Neale B, Medland S, Ripke S, Anney R, Asherson P, Buitelaar J, et al. Case-control genome-wide association study of attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry, 2010, 49(9): 906-920. [Crossref]

17. Sun X, He C, Yang S, Li W, & Qu H. Mendelian randomization to evaluate the effect of folic acid supplement on the risk of Alzheimer disease. Medicine, 2024, 103(6): e37021. [Crossref]

18. Jansen P, Nagel M, Watanabe K, Wei Y, Savage J, de Leeuw C, et al. Genome-wide meta-analysis of brain volume identifies genomic loci and genes shared with intelligence. Nature Communications, 2020, 11(1): 5606. [Crossref]

19. Bowden J, Davey Smith G, Haycock P, & Burgess S. Consistent estimation in mendelian randomization with some invalid instruments using a weighted median estimator. Genet Epidemiol, 2016, 40(4): 304-314. [Crossref]

20. Burgess S, Butterworth A, & Thompson S. Mendelian randomization analysis with multiple genetic variants using summarized data. Genet Epidemiol, 2013, 37(7): 658-665. [Crossref]

21. Hartwig F, Davey Smith G, & Bowden J. Robust inference in summary data Mendelian randomization via the zero modal pleiotropy assumption. Int J Epidemiol, 2017, 46(6): 1985-1998. [Crossref]

22. Verbanck M, Chen C, Neale B, & Do R. Detection of widespread horizontal pleiotropy in causal relationships inferred from Mendelian randomization between complex traits and diseases. Nat Genet, 2018, 50(5): 693-698. [Crossref]

23. Sanderson E. Multivariable mendelian randomization and mediation. Cold Spring Harb Perspect Med, 2021, 11(2): a038984. [Crossref]

24. Hemani G, Zheng J, Elsworth B, Wade K, Haberland V, Baird D, et al. The MR-Base platform supports systematic causal inference across the human phenome. Elife, 2018, 7: 34408. [Crossref]

25. Spiller W, Bowden J, & Sanderson E. Estimating and visualising multivariable Mendelian randomization analyses within a radial framework. PLoS Genet, 2024, 20(12): e1011506. [Crossref]

26. Fekete M, Varga P, Ungvari Z, Fekete J, Buda A, Szappanos Á, et al. The role of the Mediterranean diet in reducing the risk of cognitive impairement, dementia, and Alzheimer’s disease: a meta-analysis. Geroscience, 2025, 47(3): 3111-3130. [Crossref]

27. de Levante Raphael D. The Knowledge and attitudes of primary care and the barriers to early detection and diagnosis of Alzheimer’s disease. Medicina, 2022, 58(7): 906-915. [Crossref]

28. Cıngar Alpay K, Heybeli C, Bilgic I, Tanriverdi I, Beydilli S, Behzad A, et al. Appetite loss in older adults without undernutrition: associated factors and clinical implications. BMC Geriatr, 2025, 25(1): 641-652. [Crossref]

29. Hardman R, Meyer D, Kennedy G, Macpherson H, Scholey A, & Pipingas A. Findings of a pilot study investigating the effects of mediterranean diet and aerobic exercise on cognition in cognitively healthy older people living independently within aged-care facilities: the lifestyle intervention in independent living aged care (LIILAC) study. Curr Dev Nutr, 2020, 4(5): nzaa077. [Crossref]

30. Knight A, Bryan J, Wilson C, Hodgson J, Davis C, & Murphy K. The mediterranean diet and cognitive function among healthy older adults in a 6-month randomised controlled trial: the medley study. Nutrients, 2016, 8(9): 579-589. [Crossref]

31. Martínez-Lapiscina E, Galbete C, Corella D, Toledo E, Buil-Cosiales P, Salas-Salvado J, et al. Genotype patterns at CLU, CR1, PICALM and APOE, cognition and Mediterranean diet: the PREDIMED-NAVARRA trial. Genes Nutr, 2014, 9(3): 393-408. [Crossref]

32. Teng F, Sun J, Chen Z, & Li H. Genetically determined dietary habits and risk of Alzheimer’s disease: a Mendelian randomization study. Front Nutr, 2024, 11: 1415555. [Crossref]

33. Benn M, & Nordestgaard B. From genome-wide association studies to Mendelian randomization: novel opportunities for understanding cardiovascular disease causality, pathogenesis, prevention, and treatment. Cardiovasc Res, 2018, 114(9): 1192-1208. [Crossref]

34. Williams D, Finan C, Schmidt A, Burgess S, & Hingorani A. Lipid lowering and Alzheimer disease risk: a mendelian randomization study. Ann Neurol, 2020, 87(1): 30-39. [Crossref]

35. Kim H, Ang T, Thomas R, Lyons M, & Au R. Long-term blood pressure patterns in midlife and dementia in later life: findings from the Framingham Heart Study. Alzheimers Dement, 2023, 19(10): 4357-4366. [Crossref]

36. den Brok M, van Dalen J, Marcum Z, Busschers W, van Middelaar T, Hilkens N, et al. Year-by-Year blood pressure variability from midlife to death and lifetime dementia risk. JAMA Netw Open, 2023, 6(10): e2340249. [Crossref]

37. Flynn M, Tierney A, & Itsiopoulos C. Is extra virgin olive oil the critical ingredient driving the health benefits of a mediterranean diet? A narrative review. Nutrients, 2023, 15(13): 2916-2928. [Crossref]

38. Clemente-Suárez V, Beltrán-Velasco A, Redondo-Flórez L, Martín-Rodríguez A, & Tornero-Aguilera J. Global impacts of western diet and its effects on metabolism and health: a narrative review. Nutrients, 2023, 15(12): 2749-2760. [Crossref]

SUPPLEMENTARY

Table S1.

A list of SNP IDs used as instrumental variables for olive oil consumption, including their association statistics (effect size, standard error, P-value) and F-statistics.

| d.exposure | hr.exposur | os. exposure | SNP | effect_allele.exposur | other_allele.exposur | eaf.exposure | beta.exposure | se.exposure | pval.exposure | samplesize.exposur | Exposure | mr_keep.exposur | pval_origin.exposur | data_source.exposur | Fstat |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ukb-b-3875 | 7 | 19753063 | rs6966854 | G | A | 0.040778 | 0.034646 | 0.006683 | 2.20E-07 | 64949 | Type of fat/oil used in cooking: oliveoil || id:ukb-b-3875 | TRUE | reported | igd | 26.87238 |

| ukb-b-3875 | 8 | 6214193 | rs11137009 | A | C | 0.44701 | -0.01351 | 0.002728 | 7.30E-07 | 64949 | Type of fat/oil used in cooking:oliveoil || id:ukb-b-3875 | TRUE | reported | igd | 24.52631 |

| ukb-b-3875 | 11 | 1.01E+08 | rs7128860 | T | G | 0.250165 | -0.01536 | 0.003181 | 1.40E-06 | 64949 | Type of fat/oil used in cooking: oliveoil || id:ukb-b-3875 | TRUE | reported | igd | 23.31884 |

| ukb-b-3875 | 5 | 62866262 | rs2161277 | T | C | 0.098237 | -0.02119 | 0.004446 | 1.90E-06 | 64949 | Type of fat/oil used in cooking: oliveoil || id:ukb-b-3875 | TRUE | reported | igd | 22.72112 |

| ukb-b-3875 | 7 | 1.11E+08 | rs6965810 | C | T | 0.67165 | 0.013377 | 0.002825 | 2.20E-06 | 64949 | Type of fat/oil used in cooking: oliveoil || id:ukb-b-3875 | TRUE | reported | igd | 22.41863 |

| ukb-b-3875 | 1 | 2.08E+08 | rs1152834 | C | T | 0.587622 | -0.01308 | 0.002771 | 2.40E-06 | 64949 | Type of fat/oil used in cooking: oliveoil || id:ukb-b-3875 | TRUE | reported | igd | 22.27429 |

| kb-b-3875 | 9 | 31260309 | rs10970249 | T | C | 0.066244 | 0.024735 | 0.00534 | 3.60E-06 | 64949 | Type of fat/oil used in cooking: oliveoil || id:ukb-b-3875 | TRUE | reported | igd | 21.45864 |

| ukb-b-3875 | 10 | 27689092 | rs3004203 | G | A | 0.945934 | -0.02667 | 0.005833 | 4.80E-06 | 64949 | Type of fat/oil used in cooking: oliveoil || id:ukb-b-3875 | TRUE | reported | igd | 20.91318 |

| ukb-b-3875 | 3 | 267463 | rs62228289 | C | T | 0.066754 | 0.02488 | 0.005453 | 5.00E-06 | 64949 | Type of fat/oil used in cooking: oliveoil || id:ukb-b-3875 | TRUE | reported | igd | 20.81852 |

| ukb-b-3875 | 7 | 19753063 | rs6966854 | G | A | 0.040778 | 0.034646 | 0.006683 | 2.20E-07 | 64949 | Type of fat/oil used in cooking: oliveoil || id:ukb-b-3875 | TRUE | reported | igd | 26.87238 |

Table S2. Detailed harmonized SNP-level data for the Mendelian randomization analysis of olive oil consumption and Alzheimer’s disease.

Variables include exposure, outcome, GWAS IDs, sample size, SNP identifier, effect estimate (β), standard error (SE), and P-value.

| xposure | Outcome | Id.exposure | Id.outcome | Samplesize | SNP | b | se | P |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Type of fat/oil used in cooking: Olive oil || id:ukb-b-3875 | Alzheimer's disease || id:ieu-b-5067 | ukb-b-3875 | ieu-b-5067 | 488285 | rs10970249 | 0.001726425 | 0.003536 | 0.625365 |

| Type of fat/oil used in cooking: Olive oil || id:ukb-b-3875 | Alzheimer's disease || id:ieu-b-5067 | ukb-b-3875 | ieu-b-5067 | 488285 | rs11137009 | -1.60E-04 | 0.002914 | 0.956262 |

| Type of fat/oil used in cooking: Olive oil || id:ukb-b-3875 | Alzheimer's disease || id:ieu-b-5067 | ukb-b-3875 | ieu-b-5067 | 488285 | rs1152834 | 0.002459371 | 0.00344 | 0.474625 |

| Type of fat/oil used in cooking: Olive oil || id:ukb-b-3875 | Alzheimer's disease || id:ieu-b-5067 | ukb-b-3875 | ieu-b-5067 | 488285 | rs2161277 | 7.07E-04 | 0.003354 | 0.832957 |

| Type of fat/oil used in cooking: Olive oil || id:ukb-b-3875 | Alzheimer's disease || id:ieu-b-5067 | ukb-b-3875 | ieu-b-5067 | 488285 | rs3004203 | 0.002181856 | 0.003488 | 0.53163 |

| Type of fat/oil used in cooking: Olive oil || id:ukb-b-3875 | Alzheimer's disease || id:ieu-b-5067 | ukb-b-3875 | ieu-b-5067 | 488285 | rs62228289 | 0.001156152 | 0.003469 | 0.738938 |

| Type of fat/oil used in cooking: Olive oil || id:ukb-b-3875 | Alzheimer's disease || id:ieu-b-5067 | ukb-b-3875 | ieu-b-5067 | 488285 | rs6965810 | 0.004045347 | 0.00259 | 0.11829 |

| Type of fat/oil used in cooking: Olive oil || id:ukb-b-3875 | Alzheimer's disease || id:ieu-b-5067 | ukb-b-3875 | ieu-b-5067 | 488285 | rs6966854 | 0.001881223 | 0.00358 | 0.599259 |

| Type of fat/oil used in cooking: Olive oil || id:ukb-b-3875 | Alzheimer's disease || id:ieu-b-5067 | ukb-b-3875 | ieu-b-5067 | 488285 | rs7128860 | 0.001438776 | 0.003537 | 0.684129 |

| Type of fat/oil used in cooking: Olive oil || id:ukb-b-3875 | Alzheimer's disease || id:ieu-b-5067 | ukb-b-3875 | ieu-b-5067 | 488285 | All | 0.001717318 | 0.003129 | 0.583105 |