Open Access | Case

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-ShareAlike 4.0 International License.

Untreated hip fracture as a trigger for rapid frailty progression: a case report

* Corresponding author: Novira Widajanti

Mailing address: Division of Geriatrics, Department of Internal Medicine, Faculty of Medicine, Universitas Airlangga Dr. Soetomo Teaching Hospital, Faculty of Medicine Universitas Airlangga Jl. Mayjend Prof. Dr. Moestopo 47 Surabaya 60131, Indonesia.

Email: novirawidajanti@fk.unair.ac.id

Received: 24 September 2025 / Revised: 23 October 2025 / Accepted: 21 November 2025 / Published: 30 December 2025

DOI: 10.31491/APT.2025.12.197

Abstract

The growing elderly population has amplified the burden of frailty, falls, and their complications. Frailty, often linked to sarcopenia, predisposes older adults to disability, mortality, and hip fracture as the most severe consequence. We report an 83-year-old woman with an untreated hip fracture who developed prolonged immobility, pressure ulcers, and rapid frailty progression (Barthel index ADL: 20 pre-fall, 2 before admission, 0 at admission; Rockwood 8). Imaging revealed a comminuted femoral neck fracture, vertebral collapse, and subacute ischemic infarction. Despite multidisciplinary care, she developed pneumonia with type 1 respiratory failure and died on day five of hospitalization. This case highlights how an untreated hip fracture can trigger a cascade of complications and accelerate frailty, emphasizing the need for early assessment, timely fracture management, and preventive strategies in geriatric care.

Keywords

Frailty, falls, untreated fracture, geriatric syndrome, pressure ulcer

Introduction

The global elderly population has risen substantially in recent decades, reflecting increased life expectancy but also greater vulnerability to health problems related to aging and socio-demographic factors [1]. Among the various consequences of population aging, frailty – often associated with sarcopenia – stands out as a key clinical challenge, reflecting the decline in physiological resilience and increasing vulnerability to adverse outcomes such as falls, delirium, and functional disability [2]. Falls in older adults can cause various injuries, with hip fractures being the most severe, often resulting in substantial loss of mobility, independence, and quality of life, as well as increased morbidity and mortality [3, 4]. The incidence of hip fractures in older adults varies widely across regions; for instance, Denmark reports the world’s highest rate (315.9 per 100,000), whereas Brazil shows a markedly lower rate (95.1 per 100,000) [4]. A study from India reported that untreated hip fractures in the elderly significantly impair quality of life [5]. Unfortunately, epidemiological studies on hip fractures in Indonesia are scarce, and data specifically addressing untreated cases are currently unavailable. Hip fractures both signify and accelerate frailty. Elevated catabolic cytokines from the acute-phase response, together with immunosenescence, contribute to muscle wasting, inflammation, increased susceptibility to infection, and poor healing. In addition, immobilization leads to disuse atrophy of muscle and bone. These interconnected changes create a self-perpetuating “frailty loop,” where malnutrition, sarcopenia, and cognitive decline reinforce one another [4]. Here, we report a case of a geriatric patient with an untreated hip fracture illustrating its role in the rapid progression of frailty.

Case report

An 83-year-old woman was referred to our hospital with decreased consciousness, fever, anemia, and hypokalemia. One day prior, she developed high fever and progressive unresponsiveness; two weeks earlier she had rightsided weakness, slurred speech, and loss of appetite. She had been bedridden for 3 months prior to admission following a fall that caused severe left hip pain suggestive of fracture, but refused hospitalization and medical treatment, expressing a preference to remain at home due to advanced age and a desire for comfort. Despite the family’s repeated efforts to persuade her, they ultimately respected her decision in accordance with her wishes for comfort and autonomy. Since then, she was immobile and developed a sacral ulcer. Previously, she was independent in daily activities. The patient came from a middle socioeconomic background and lived with her daughter, son-in-law, three grandchildren, and a household assistant who accompanied her daily. Most of the time, she stayed at home under the supervision of the household assistant, who was not medically trained. Past medical history included recurrent falls and untreated hypertension; no diabetes or major systemic disease. On arrival, she was in poor condition (GCS 9/15, BMI 18.7 kg/m²), with stable vital signs and pale conjunctiva. Neurological examination revealed right facial palsy, right hemiparesis, and National Institutes of Health Stroke Scale (NIHSS) 24. Pressure ulcers were identified on the sacrum (grade 4) and the right hip (grade 3).

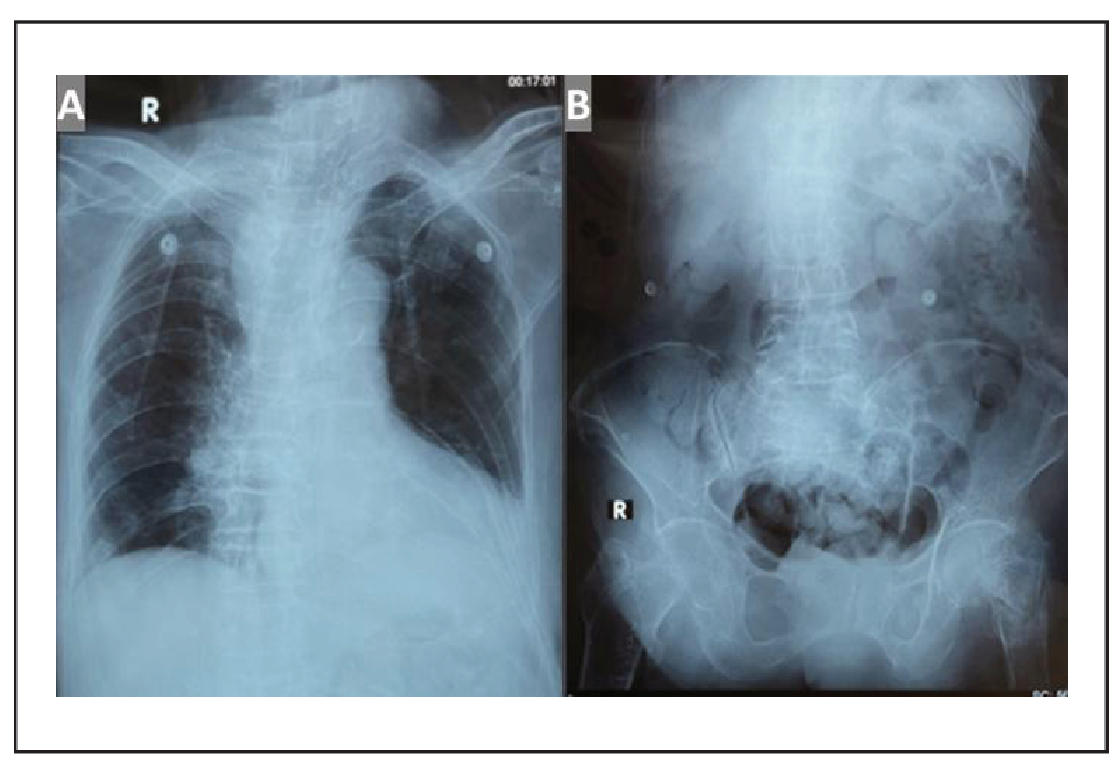

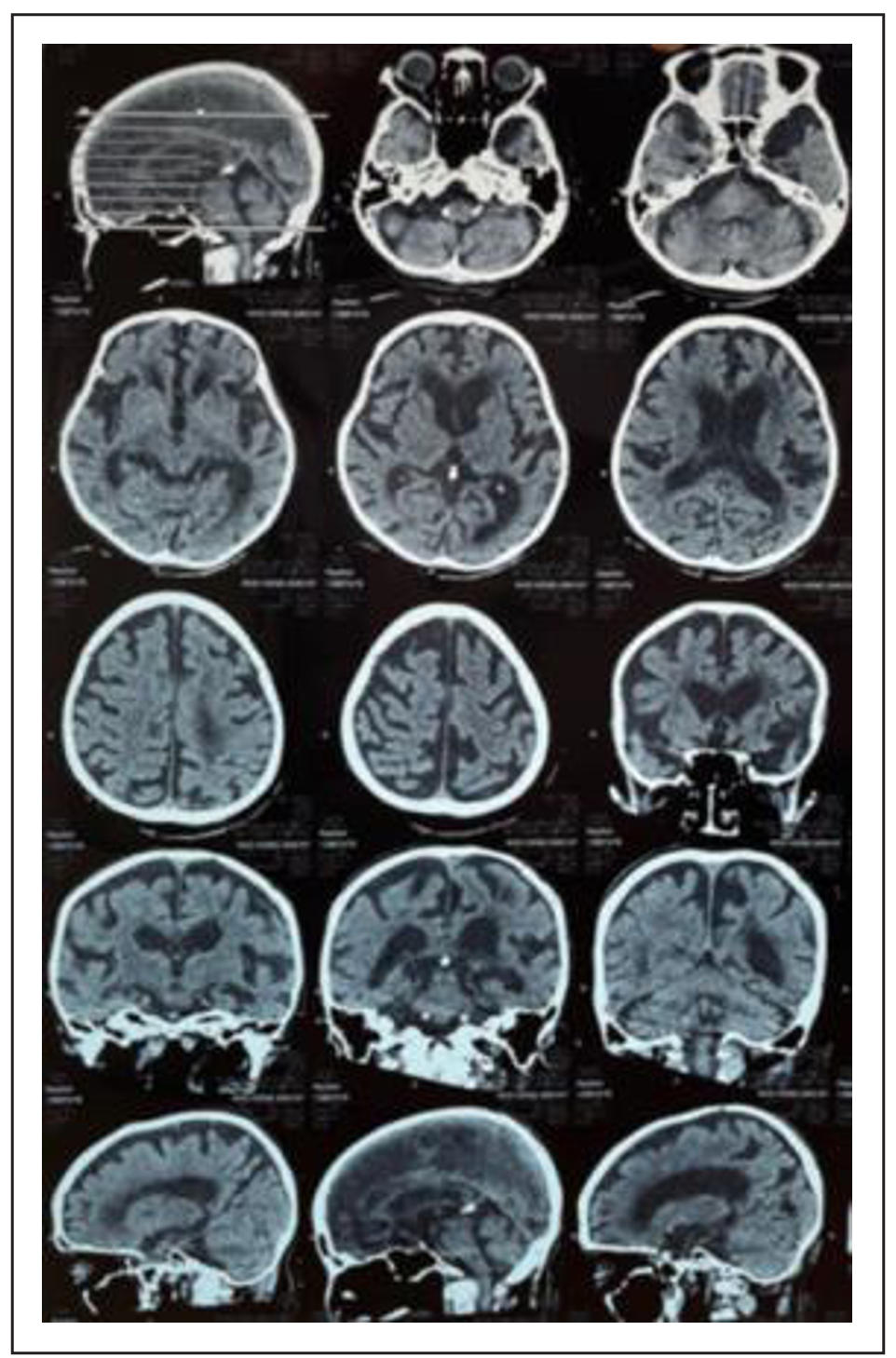

The complete laboratory findings are presented in Table 1. The deterioration of the comprehensive geriatric assessment (CGA) before and after the hip fracture is summarized in Table 2. Chest X-ray showed cardiomegaly and vertebral collapse (Figure 1A); abdominal X-ray revealed a comminuted femoral neck fracture (Figure 1B); and brain CT showed subacute-to-chronic left thalamic infarction with atrophy (Figure 2).

Figure 1. (A) Chest radiograph showing no pulmonary abnormalities, cardiomegaly with aortic atherosclerosis, and collapse of thoracic vertebral bodies (VTh) 2, 4, 5, 6, 7, and 8, accompanied by thoracic scoliosis with rightward convexity; (B) Abdominal X-ray showing a comminuted fracture of the left femoral neck. No evidence of ileus or pneumoperitoneum is observed.

Figure 2. Non-contrast brain MSCT showing subacute to chronic ischemic cerebral infarction in the left thalamus, accompanied by brain atrophy.

Table 1.

Laboratory findings.

| Variable | Day-1 of admission | Day-4 of admission |

|---|---|---|

| Hemoglobin (g/dL) | 8.8 | 11.6 |

| Hematocrit (%) | 26.6 | 35.2 |

| MCV (fl) | 93.7 | 89.3 |

| MCH (pg) | 31 | 29.4 |

| MCHC (g/dL) | 33.1 | 33 |

| Leukocyte (103/uL) | 8.9 | 13.36 |

| Lymphocyte (%) | 12.8 | 6.8 |

| Neutrophile (%) | 81.6 | 87.5 |

| Platelets (103/uL) | 298 | 186 |

| Sodium (mEq/L) | 143 | 138 |

| Potassium (mEq/L) | 2.5 | 4.2 |

| Chloride (mEq/L) | 104 | 103 |

| Blood glucose (mg/dL) | 123 | 108 |

| AST (U/L) | 21 | - |

| ALT (U/L) | 13.8 | - |

| CRP (mg/L) | 2.4 | - |

| BUN (mg/dL) | 45 | 28.6 |

| Creatinine serum (mg/dL) | 0.8 | 0.59 |

| Albumin serum (mg/dL) | 3.28 | - |

| Blood gas analysis | ||

| pH | 7.56 | 7.41 |

| pCO2 | 33 | 47 |

| pO2 | 162 | 38 |

| BE | 7.3 | 5.2 |

| HCO3 | 29.5 | 29.8 |

| SpO2 | 100% | 73% |

| FiO2 | 33% | 90% |

Note: AST: aspartate aminotransferase; ALT: alanine aminotransferase; BE: base excess; BUN: blood urea nitrogen; CRP: C-reactive protein; FiO2: fraction of inspired oxygen; HCO3: hydrogen carbonate ion (bicarbonate); MCH: mean corpuscular hemoglobin; MCHC: mean corpuscular hemoglobin concentration; MCV: mean corpuscular volume; pCO2: partial pressure of carbon dioxide; pH: potential hydrogen; pO2: partial pressure of oxygen; SpO2: peripheral oxygen saturation.

Table 2.

CGA before and after the hip fracture.

| Assessment | Before hip fracture | After hip fracture | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 3 months before admission | 2 months before admission | After stroke (2 weeks before admission) | On admission | ||

| ADL | 20 (independent) | 8 (severe dependency) | 6 (severe dependency) | 2 (total dependency) | 0 (total dependency) |

| Rockwood Frailty Score | 3 managing well | 7 severely frail | 7 severely frail | 8 very severely frail | 8 very severely frail |

| MNA |

N/A (not assessed) |

N/A | N/A | N/A | Screening score 3, Recitation scores 7, Total: 10 (malnutrition) |

| MMSE | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A |

| GDS | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A |

| Well’s score | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | 2 (moderate risk DVT) |

| CHADS2 VASC score | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | 6 (9.7%) (medium-high stroke probability) |

| IMPROVE VTE | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | 4 (2.9% 3-month risk of VTE) |

| Norton score | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | 5 (high probability of decubitus) |

| WFG Risk of falling | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | High risk of falling |

| CAM | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | Positive (delirium) |

Note: ADL: activities of daily living; CAM: confusion assessment method; GDS: geriatric depression scale; MMSE: mini-mental state examination; MNA: mini nutritional assessment; WFG: world falls guidelines.

Final diagnoses included multiorgan failure syndrome secondary to an untreated femoral neck fracture with septic/hypoxic encephalopathy, sub-acute to chronic ischemic cerebral infarction, sepsis, and multiple geriatric syndromes (delirium, very severely frail, total dependency, malnutrition, moderate risk of deep vein thrombosis, pressure ulcers, community acquired pneumonia, constipation, and high risk of falling). Additional diagnoses included anemia, hypokalemia, and uncontrolled hypertension. The patient received supportive and multidisciplinary care, including oxygenation, gradual enteral feeding via nasogastric tube, intravenous fluids supplemented with potassium, and blood transfusion. Intravenous antibiotics were administered (ceftriaxone 1 g every 12 hours and metronidazole 500 mg every 8 hours), along with aspirin 100 mg daily, vitamin B12, and antihypertensive therapy.

She was comanaged with the neurology and plastic surgery teams. Regular ulcer debridement was performed every 3–5 days. Preventive measures for immobilization complications included 45° head elevation, frequent repositioning every 1–2 hours, passive range-of-motion exercises, use of an air mattress and pillows to reduce pressure and friction, topical oil application to prevent maceration, and abdominal and leg muscle strengthening exercises to reduce deep vein thrombosis risk (DVT). For constipation, fleet enemas were given three times daily.

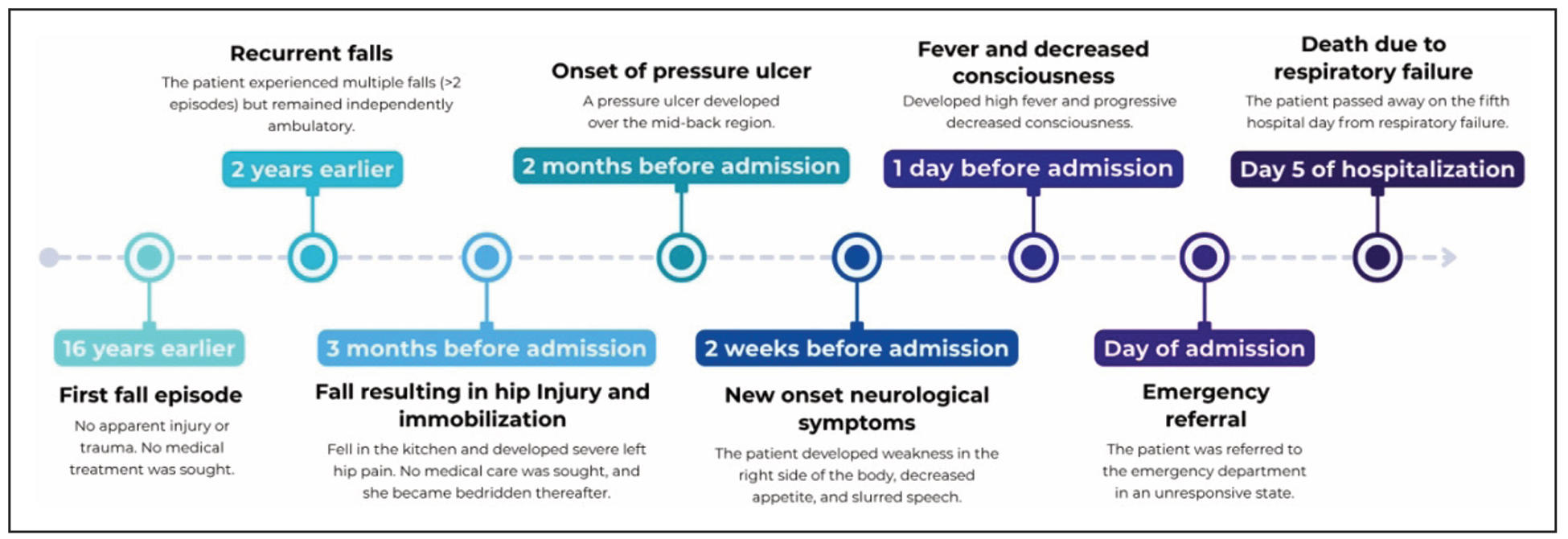

On day 3 of hospitalization, the patient developed type 1 respiratory failure, likely secondary to pneumonia or aspiration. Laboratory results revealed leukocytosis (13360/μL) with neutrophil predominance (87.5%) and correction of hypokalemia (4.2 mEq/L) (Table 2). Despite intensive care, her condition continued to deteriorate, and she passed away on day 5 of hospitalization after the family requested a Do Not Resuscitate (DNR) order. The timeline of clinical progression from the first fall episode to the deteriorating condition on admission and death is shown in Figure 3.

Figure 3. Timeline of clinical progression.

Discussion

Frailty markedly increases the risk of falls and related injuries in older adults, with intrinsic factors (e.g., sensory and motor decline, balance disorders, dementia, stroke, sarcopenia) and extrinsic factors (environmental hazards) contributing to vulnerability [6, 7]. Among fall-related injuries, hip fracture represents the most common and most serious event in geriatrics. It is associated with severe functional decline, long-term disability, and up to a 15 fold higher mortality within the first month after fracture [8, 9]. Hip fracture is also strongly associated with ADL disability, frailty progression, and greater demand for daily care [10]. Early CGA is therefore crucial to detect modifiable risk factors, guide prevention, and optimize outcomes [11, 12]. In our patient, functional status deteriorated sharply after sustaining an untreated hip fracture. Her ADL score fell from 20 (independent) before illness, to 2 (total dependency) prior to admission, and ultimately to 0 (total dependence) at presentation. Prolonged immobilization due to the untreated fracture contributed to persistent bedridden status and complications such as pressure ulcers, infections, and respiratory compromise.

Frailty, frequently associated with sarcopenia, is a syndrome of progressive functional decline that signals an elevated and often unpredictable risk of falls. One of the most practical frailty assessment tools is the Rockwood Clinical Frailty Scale, which categorizes frailty into nine stages from “very fit” (1) to “terminally ill” (9) [13, 14].

In this case, CGA demonstrated rapid frailty progression, from “managing well” before fracture to “very severely frail” at admission. Frailty progression is a strong predictor of adverse outcomes, including prolonged hospitalization and mortality in hip fracture patients [15]. In our patient, this trajectory of frailty progression directly paralleled her poor clinical course and eventual decline, underscoring the importance of timely recognition and intervention.

Untreated hip fractures are rarely documented in the clinical literature. A recent report by Najafi et al. described two cases of simultaneous untreated bilateral femoral neck fractures. The first patient was a 65-year-old woman diagnosed with bilateral femoral fractures 40 days after a car accident, while the second was a 45-year-old man identified with bilateral femoral neck fractures 35 days after lifting a heavy load. Both patients had a history of heroin abuse, which may have masked the pain and contributed to the delayed diagnosis, and were ultimately treated successfully with bipolar hemiarthroplasty. These cases highlight the diagnostic challenges and severe outcomes associated with delayed management, although both were eventually treated surgically [16]. Similarly, our case demonstrates how an untreated hip fracture in a frail older adult can trigger a cascade of complications, underscoring the critical importance of early recognition and timely intervention to prevent rapid frailty progression and mortality.

Beyond frailty itself, the consequences of immobility in older adults are profound. Approximately 25% of immobilized older adults who fall may die as a result of stroke, which tends to cause more severe complications in geriatric patients than in younger populations. These include immobility, dysphagia, delirium, infections, malnutrition, and recurrent falls. Prolonged immobilization can further lead to numerous complications. These include musculoskeletal problems such as regional pain and reduced range of motion; respiratory complications like hypostatic pneumonia; and gastrointestinal disturbances such as fecal impaction. All of these complications can further result in dehydration, malnutrition, pressure ulcers, renal calculi, and thromboembolic events [17]. Immobilization, stroke, and age-related processes such as endothelial dysfunction increase the risk of venous thromboembolism (VTE), including DVT and pulmonary embolism (PE) [18]. In this patient, prolonged immobility was followed by a stroke two months later, further worsening her frailty status and overall prognosis. Stroke sequelae also contributed to decubitus ulcer formation and increased her risk of VTE, evidenced by a Well’s score of 2 (moderate risk).

Stroke frequently leads to dysphagia, a complication that not only worsens malnutrition but also predisposes patients to aspiration and pneumonia. Reportedly, 22–65% of stroke patients develop dysphagia, with an incidence of 12–67% within three days of stroke onset. Aspiration occurs in about 10% of dysphagic patients, and up to 33% develop aspiration pneumonia, which substantially increases mortality. An NIHSS ≥ 12 at admission is predictive of subsequent dysphagia [19]. In our case, the patient presented with severe stroke (NIHSS 24) and developed dysphagia, which contributed to worsening pneumonia, nutritional deficits, and delirium. Her respiratory failure was likely multifactorial, arising from aspiration, infection, and the possibility of PE.

Management of complications in such complex geriatric cases requires a multidisciplinary approach. For pressure ulcers, preventive measures include frequent repositioning, pressure-relieving mattresses, and meticulous skin care. Once ulcers develop, treatment strategies involve debridement, analgesics, and targeted antibiotics, with vancomycin reserved for MRSA infection. Pain relief may be optimized with moist or hydrocolloid dressings. Nutritional support is equally critical, given that malnutrition increases ulcer risk fourfold. Recommendations include caloric intake of 30–35 kcal/kg/day and protein intake of 1.25–1.5 g/kg/day, in addition to micronutrient and multivitamin supplementation [20].

Frailty and fall-risk assessment should ideally be conducted early, even before major injuries such as hip fracture occur. The World Falls Guidelines (WFG) recommend exercise, sensory evaluation, osteoporosis assessment, vitamin D, and analgesia, with multidisciplinary strategies for high-risk patients such as mobilization, hydration, bowel management, and cognitive support. The WFG also emphasizes the crucial role of caregivers in fall prevention for high-risk older adults, advocating for tailored care plans that incorporate patient values through active collaboration and education of both formal and informal caregivers [6]. Beyond the individual and family level, community-based interventions also play an important role. The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) highlights that participation in evidence-based community fall prevention programs has been shown to reduce fall incidence by approximately 30–35% compared with those who did not participate [21]. In line with these recommendations, incorporating physical exercise combined with fracture-prevention measures is expected to further reduce fall risk and slow frailty progression. Frailty prevention through resistance training and fall-prevention exercises can reduce fracture risk [7, 8, 22].

Caregivers also play a vital role in minimizing complications once immobilization has occurred. However, Dhakal et al. found that most caregivers in their study had limited awareness of strategies to prevent complications related to immobility [17]. Enhancing caregiver education on postfall and post-fracture care is therefore essential to mitigate further functional decline in frail older adults. In this case, the cascade of complications—from an untreated hip fracture to immobility, malnutrition, infection, pressure ulcers, stroke, and rapid frailty progression—highlights the interplay between frailty and adverse geriatric outcomes. Unfortunately, the lack of timely fracture management and subsequent immobilization triggered an irreversible downward spiral that culminated in poor functional recovery and early mortality.

The novelty of this report lies in documenting how an untreated hip fracture in a frail elderly patient served as the initial trigger for a cascade of synergistic complications—immobility, infection, malnutrition, pressure ulcers, and stroke—that collectively accelerated frailty progression. While the association between hip fracture and frailty has been well recognized, the longitudinal demonstration of this cascade in a single patient underscores the need for timely intervention at every step, from fracture management to frailty prevention and post-stroke care.

Conclusions

In conclusion, this case illustrates that failure to address a hip fracture in a frail older adult can initiate a series of complications that reinforce one another, resulting in progressive frailty and early mortality. It highlights the importance of timely and multidisciplinary management, not only of the fracture itself but also of the broader geriatric syndromes that converge in such cases. Reflecting on this case, we are reminded that each missed opportunity for intervention in frailty care compounds the next, emphasizing the urgency of proactive and integrated management in vulnerable elderly populations.

Declarations

Acknowledgment

We would like to thank Dr. Soetomo General Academic Hospital for providing the essential data, access to the patient, and facilities required to this study.

Authors contribution

Conceptualization, data curation, formal analysis, and project administration were performed by Anggraeni MR, Widiasi ED, and Widajanti N. Writing – original draft was carried out by Anggraeni MR and Widiasi ED. Supervision, as well as writing – review and editing, were conducted by Widajanti N. All authors have read and approved the final manuscript and agreed to be accountable for all aspects of the work.

Availability of data and materials

Not applicable.

Financial support and sponsorship

None.

Conflict of interest

All authors declared that there are no conflicts of interest.

Consent for publication

Written informed consent was obtained from the patient during admission to unveil the case details, including the examination results and other accompanying images, for publication and educational purposes.

References

1. Rudnicka E, Napierała P, Podfigurna A, Męczekalski B, Smolarczyk R, & Grymowicz M. The World Health Organization (WHO) approach to healthy ageing. Maturitas, 2020, 139: 6-11. [Crossref]

2. Clegg A, Bates C, Young J, Ryan R, Nichols L, Ann Teale E, et al. Development and validation of an electronic frailty index using routine primary care electronic health record data. Age Ageing, 2016, 45(3): 353-360. [Crossref]

3. Lim S, Choi K, Heo N, Kim Y, & Lim J. Characteristics of fragility hip fracture-related falls in the older adults: a systematic review. J nutrition, health & aging, 2024, 28(10): 100357. [Crossref]

4. Andaloro S, Cacciatore S, Risoli A, Comodo R, Brancaccio V, Calvani R, et al. Hip fracture as a systemic disease in older adults: a narrative review on multisystem implications and management. Med Sci, 2025, 13(3): 89-100. [Crossref]

5. Prasad J, Varghese A, Jamkhandi D, Chakraborty A, Rakesh P, & Abraham V. Quality-of-Life among elderly with untreated fracture of neck of femur: a community based study from Southern India. J Family Med Prim Care, 2013, 2(3): 270-273. [Crossref]

6. Montero-Odasso M, van der Velde N, Martin F, Petrovic M, Tan M, Ryg J, et al. World guidelines for falls prevention and management for older adults: a global initiative. Age Ageing, 2022, 51(9): afac205. [Crossref]

7. Pasquetti P, Apicella L, & Mangone G. Pathogenesis and treatment of falls in elderly. Clin Cases Miner Bone Metab, 2014, 11(3): 222-225.

8. McDonough C, Harris-Hayes M, Kristensen M, Overgaard J, Herring T, Kenny A, et al. Physical therapy management of older adults with hip fracture. J Orthop Sports Phys Ther, 2021, 51(2): Cpg1-cpg81. [Crossref]

9. Segev-Jacubovski O, Magen H, & Maeir A. Functional ability, participation, and health-related quality of life after hip fracture. OTJR, 2019, 39(1): 41-47. [Crossref]

10. Ouellet J, Ouellet G, Romegialli A, Hirsch M, Berardi L, Ramsey C, et al. Functional outcomes after hip fracture in independent community-dwelling patients. J Am Geriatr Soc, 2019, 67(7): 1386-1392. [Crossref]

11. Fischer H, Maleitzke T, Eder C, Ahmad S, Stöckle U, & Braun K. Management of proximal femur fractures in the elderly: current concepts and treatment options. Eur J Med Res, 2021, 26(1): 86-98. [Crossref]

12. Rashidifard C, Romeo N, Muccino P, Richardson M, & DiPasquale T. Palliative management of nonoperative femoral neck fractures with continuous peripheral pain catheters: 20 patient case series. Geriatr Orthop Surg Rehabil, 2017, 8(1): 34-38. [Crossref]

13. Gagesch M, Chocano-Bedoya P, Abderhalden L, Freystaetter G, Sadlon A, Kanis JA, et al. Prevalence of physical frailty: results from the DO-HEALTH study. J Frailty Aging, 2022, 11(1): 18-25. [Crossref]

14. "Healthcare Improvement Scotland." from https://www.healthcareimprovementscotland.scot/. 2025.

15. Song Y, Wu Z, Huo H, & Zhao P. The impact of frailty on adverse outcomes in geriatric hip fracture patients: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Front Public Health, 2022, 10: 890652. [Crossref]

16. Najafi A, Azarsina S, Hadavi D, Arkian R, Hatamian S, & Chaghamirzayi P. Management strategies for neglected simultaneous bilateral femoral neck fractures: case report and literature review. Int J Surg Case Rep, 2024, 124: 110332. [Crossref]

17. Dhakal B. Awareness on prevention of complication related to immobility among caregivers of bedridden patients in tertiary health care center in Chitwan. Journal of College of Medical Sciences-Nepal, 18(3): 288-296. [Crossref]

18. Tritschler T, & Aujesky D. Venous thromboembolism in the elderly: a narrative review. Thromb Res, 2017, 155: 140-147. [Crossref]

19. Yang C, & Pan Y. Risk factors of dysphagia in patients with ischemic stroke: a meta-analysis and systematic review. PLoS One, 2022, 17(6): e0270096. [Crossref]

20. Halter J, Ouslander J, Studenski S, High K, Asthana S, Supiano M, et al. 2017. Hazzard's Geriatric Medicine and Gerontology, 7e. New York, NY, McGraw-Hill Education.

21. National Center for Injury Prevention and Control. Preventing falls: a guide to implementing effective community-based fall prevention programs. 2nd edition. 2015.

22. Woolford S, Sohan O, Dennison E, Cooper C, & Patel H. Approaches to the diagnosis and prevention of frailty. Aging Clin Exp Res, 2020, 32(9): 1629-1637. [Crossref]