Open Access | Research

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-ShareAlike 4.0 International License.

The loss of methionine sulfoxide reductases significantly suppresses tumor development and exacerbates kidney pathology in male quadruple Msr knockout mice

* Corresponding author: Yuji Ikeno, M.D., Ph.D.

Mailing address: Barshop Institute for Longevity and Aging Studies, The University of Texas Health Science Center at San Antonio, 4939 Charles Katz Drive, San Antonio, TX 78229, USA.

Email: ikeno@uthscsa.edu

Received: 16 September 2025 / Revised: 17 October 2025 / Accepted: 22 December 2025 / Published: 30 December 2025

DOI: 10.31491/APT.2025.12.195

Abstract

To investigate the effects of the loss of methionine sulfoxide reductase (Msr) on aging, we have conducted the survival and end-of-life pathological analyses using male quadruple Msr knockout (KO) mice lacking MsrA, MsrB1, MsrB2, and MsrB3. Our study demonstrated that the loss of Msr in male mice resulted in a similar lifespan compared to wild-type (WT) mice. The end-of-life pathology data obtained from male mice showed a significantly higher severity of glomerulonephritis in quadruple Msr KO compared to WT mice, although the incidence of fatal glomerulonephritis was similar between quadruple Msr KO and WT mice. More importantly, the incidence of fatal lymphoma and neoplastic lesions (all fatal tumors), and tumor burden were significantly less in male quadruple Msr KO than WT mice. The comorbidity index was similar between quadruple Msr KO and WT mice. Our study suggests that the loss of four Msrs did not change lifespan in male quadruple Msr KO mice compared to WT mice. The end-of-life pathology showed paradoxical results for the non-neoplastic and neoplastic lesions in male quadruple Msr KO mice. The loss of four Msrs resulted in deleterious effects on the non-neoplastic lesion, i.e., severe kidney pathology, whereas cancer development was significantly suppressed. These results call for further study into the pathophysiological roles of the loss of four Msrs in aging and agerelated pathology. Among our findings, the anti-cancer effects due to the loss of four Msrs was the most striking observation that could lead us to seek the underlying mechanisms and potential discovery of new preventive and/or therapeutic methods for certain human cancers.

Keywords

Methionine sulfoxide reductase, aging, cancer, lymphoma, glomerulonephritis, Msr KO mice

Introduction

Since Dr. Denham Harman first proposed the free radical theory of aging in the 1950s, the role of oxidative stress in aging and various age-related diseases has been extensively studied over the past 70 years. There is substantial evidence that strongly supports this theory. The levels of oxidative damage to macromolecules increase with age, and interventions (dietary, genetic, and pharmacological) extending lifespan in various animal models are correlated to reduced oxidative damage and/or increased resistance to oxidative stress both in vivo and in vitro [1-6]. However, the series of experiments using mice that genetically altered various components of the antioxidant defense system did not support the oxidative stress theory of aging with a couple of exceptions: overexpressing catalase in mitochondria (MCAT mice) and the down-regulation of Cu/ZnSOD (Cu/ZnSOD-null mice) [7-12]. Thus, a majority of the results from mice with genetically altered levels of major antioxidant enzymes seriously calls into question the exact roles of oxidative stress on the aging process in mammals.

Substantial evidence indicates important biological roles of methionine and methionine sulfoxide reductase (Msr) in cellular function and aging [13-15]. For example, methionine plays important roles in protein functions by initiating protein synthesis, maintaining protein structure, retaining redox regulation, and scavenging reactive oxygen species (ROS) to provide protection to other amino acids [13-18]. These critical biological roles of methionine may be due to the presence of Msr, which reduces methionine sulfoxide (oxidized methionine) back to methionine [19]. There are two main isoforms of Msr: MsrA and MsrB. MsrB has three subclasses in mammals (MsrB 1-3) [19-21]. To directly test the role of Msr in pathophysiology, MsrA and MsrB knockout (KO) mice have been generated. MsrA KO mice exhibited enhanced tissue/organ damages under several experimental conditions, e.g., increased sensitivity to paraquat and cisplatin, severe ischemia-reperfusion damage to kidney and brain, higher hepatotoxicity by acetaminophen, and progressive hearing loss [22-30]. Despite the increased sensitivity to oxidative stress, the survival study showed that MsrA KO mice had a similar lifespan compared to their wild-type (WT) control [22], which led us to question whether the loss of one Msr protein may not be sufficient to have a significant impact on longevity and age-related pathophysiological changes, i.e., synergistic effects by all four isoforms of Msr are required to manifest the important roles of Msr on aging. To examine whether the four isoforms of Msr have synergistic effects against oxidative stress, changes in redox signaling pathways, and pathobiology, Lai et al. generated the mouse lacking MsrA, MsrB1, MsrB2, and MsrB3 (quadruple KO mouse) [31]. The purpose of this study was to investigate the effects of the loss of four Msrs on aging by conducting the survival study and examining the end-of-life pathology using male quadruple Msr KO mice.

Methods

Animals and animal husbandry

The quadruple Msr KO mice were generated as previously described [31]. We obtained two breeding pairs, two male 200 MsrB2 × 7 MsrB3 mice and two female MsrAKO × MsrB1KO mice from Dr. Rodney Levine’s laboratory (Laboratory of Biochemistry, National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute, NIH), which were crossed to generate an aging colony of quadruple Msr KO mice with a C57BL/6 genetic background.

All mice were fed a commercial chow (Teklad Diet LM485: Madison, WI) and acidified (pH = 2.6-2.7) filtered reverse osmosis water ad libitum. To accurately measure the amount of food consumption, the actual food consumed was calculated by subtracting the weight of the spillage from the weight of the chow removed from the hopper. All of the mice were maintained under a pathogen-free environment in microisolator units with Tek FRESH® ultra laboratory bedding. Sentinel mice that were housed in the same room and exposed weekly to bedding collected from the cages of experimental mice were sacrificed on receipt and every six months thereafter for monitoring of viral antibodies (Mouse Level II Complete Antibody Profile CARB, Ectro, EDIM, GDVII, LCM, M. Ad-FL, M. Ad-K87, MCMV, MHV, M. pul., MPV, MVM,Polyoma, PVM, Reo, Sendai; BioReliance, Rockville,MD). All tests were negative.

All procedures followed the guidelines approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee at the University of Texas Health Science Center at San Antonio, and are consistent with the NIH Principles for the Utilization and Care of Vertebrate Animals Used in Testing, Research and Education, the Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals and Animal Welfare Act (National Academy Press, Washington, DC). Experiments were carried out in strict accordance with the recommendations in the Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals of the National Institutes of Health. The animal protocol (20200083AR) was approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee of the University of Texas Health Science Center at San Antonio. The animals used in this experiment were euthanized via CO2 inhalation, ensuring a humane process that minimized pain and distress.

Survival study

The mice in the survival groups were allowed to live out their lives, and the lifespan for each mouse was determined by recording the age of spontaneous death. A survival study consisting of 18 male quadruple Msr KO mice and 60 male WT mice was conducted. The survival curves were compared statistically using the log-rank and Wilcoxon tests [32]. The median, mean, and top 10th percentile (when 90% of the mice have died) survivals were calculated for each group. The median and top 10th percentile survivals for each group were compared to the WT group using a score test adapted from Wang et al. [33].

End-of-life pathological assessment

After the gross pathological examinations, the following organs and tissues were excised and preserved in 10% buffered formalin: brain, pituitary gland, heart, lung, trachea, thymus, aorta, esophagus, stomach, small intestine, colon, liver, pancreas, spleen, kidneys, urinary bladder, reproductive system (prostate, testes, epididymis, and seminal vesicles), thyroid gland, adrenal glands, parathyroid glands, psoas muscle, knee joint, sternum, and vertebrae. Any other tissues with gross lesions were also excised. The fixed tissues were processed conventionally, embedded in paraffin, sectioned at 5 microns, and stained with hematoxylin and eosin. The diagnosis of each histopathological change was made with histological classifications in aging mice as previously described [34-38]. A list of pathological lesions was constructed for each mouse that included both neoplastic and non-neoplastic diseases. Based on these histopathological data, the tumor burden, comorbidity index, and severity of each lesion were as-sessed in all mice as previously described [35-38].

Statistical analysis

Unless otherwise specified, all experiments were done at least in triplicate. Data were expressed as means ± SEM and were analyzed by the non-parametric test ANOVA. All pair-wise contrasts were computed using Tukey error protection at 95% confidence interval (CI) unless otherwise indicated. Differences were considered statistically significant at P < 0.05.

Results

Body weight

The body and organ weights of old (24-28 months) male quadruple Msr KO and WT mice are shown in Table 1. The body and organ weights were similar between quadruple Msr KO and WT mice, except for epididymal fat. Epididymal fat weight was significantly less in quadruple Msr KO compared to WT mice. Based on the body and organ weights data, there was no evidence that the loss of four Msrs affected the growth and development of male C57BL/6 mice with the exception of epididymal fat.

Table 1.

Body and organ weights of 24-28M Msr KO mice.

| WT (n = 7) | Msr KO (n = 10) | |

|---|---|---|

| Body weight | 24.95 ± 0.576 | 24.49 ± 0.599 |

| Liver | 1.331 ± 0.093 | 1.248 ± 0.108 |

| Spleen | 0.138 ± 0.053 | 0.156 ± 0.089 |

| Pancreas | 0.137 ± 0.009 | 0.123 ± 0.007 |

| Heart | 0.162 ± 0.006 | 0.169 ± 0.007 |

| Lung | 0.186 ± 0.007 | 0.201 ± 0.014 |

| Left kidney | 0.204 ± 0.015 | 0.217 ± 0.013 |

| Right kidney | 0.208 ± 0.017 | 0.236 ± 0.018 |

| Left testis | 0.071 ± 0.007 | 0.088 ± 0.004 |

| Right testis | 0.068 ± 0.006 | 0.091 ± 0.003 |

| Brain | 0.456 ± 0.006 | 0.455 ± 0.004 |

| Left quadriceps muscle | 0.139 ± 0.008 | 0.145 ± 0.011 |

| Right quadriceps muscle | 0.139 ± 0.013 | 0.152 ± 0.010 |

| Left inguinal fat | 0.071 ± 0.003 | 0.062 ± 0.006 |

| Right inguinal fat | 0.077 ± 0.008 | 0.064 ± 0.006 |

| Left perirenal fat | 0.046 ± 0.007 | 0.034 ± 0.006 |

| Right perirenal fat | 0.038 ± 0.005 | 0.031 ± 0.005 |

| Left epididymal fat | 0.142 ± 0.021 | 0.070 ± 0.015* |

| Right epididymal fat | 0.134 ± 0.020 | 0.069 ± 0.014* |

| Left subscapular fat | 0.076 ± 0.010 | 0.054 ± 0.008 |

| Right subscapular fat | 0.083 ± 0.005 | 0.069 ± 0.010 |

| Mesenteric fat | 0.129 ± 0.016 | 0.139 ± 0.014 |

Note: all weights collected in grams. *P < 0.05.

Survival curves

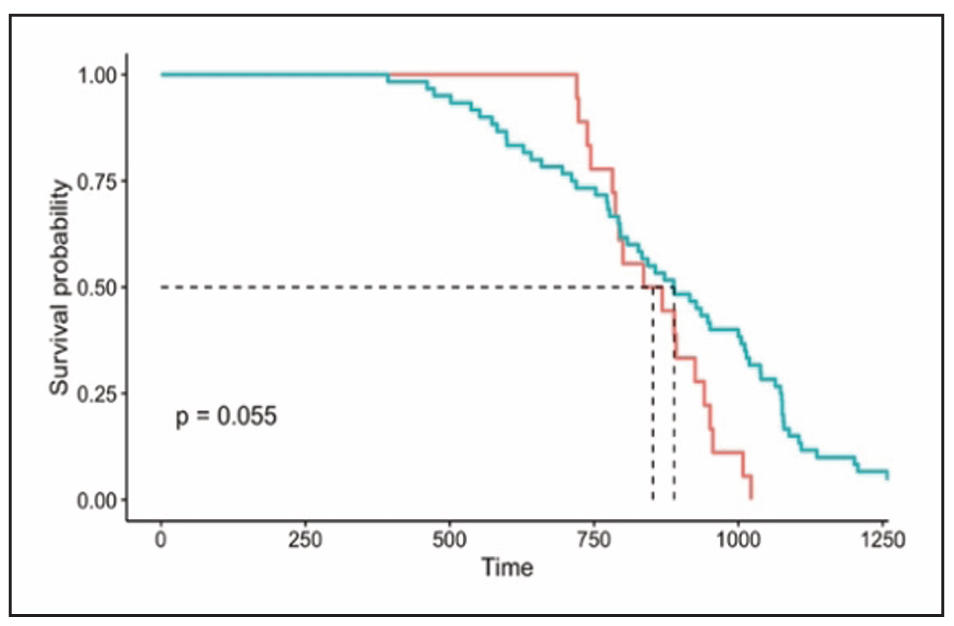

To test whether the loss of four Msrs affects aging, we conducted a survival study using male quadruple Msr KO and WT control mice. Our study showed that the survival curve of male quadruple Msr KO was not significantly different from male WT mice (Figure 1; P = 0.055). The mean, median, and 10th percentile survivals for male quadruple Msr KO and WT mice (KO/WT) were 854/881, 852/889, and 956/1,136 days, respectively (Table 2). The male quadruple Msr KO mice had slightly shorter mean (3.1%), median (4%), and 10th percentile (15.8%) lifespans compared to WT mice; however, these differences did not reach statistical significance (P > 0.05).

Table 2.

Summary statistics of Msr KO mice.

| Gender | Group | Sample size | Mean | Median | 10% survival |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Male | WT | 60 | 881 | 889 | 1136 |

| cohort | Msr KO | 18 | 854 | 852 | 956 |

Figure 1. The survival curves of male quadruple Msr KO and WT mice. The survival curves of male quadruple Msr KO (blue line) and WT (red line) mice are presented. The survival cohort consisted of 18 male quadruple Msr KO and 60 WT mice. The survival curves did not show a significant difference between male quadruple Msr KO and WT mice (P = 0.055).

End-of-life pathology

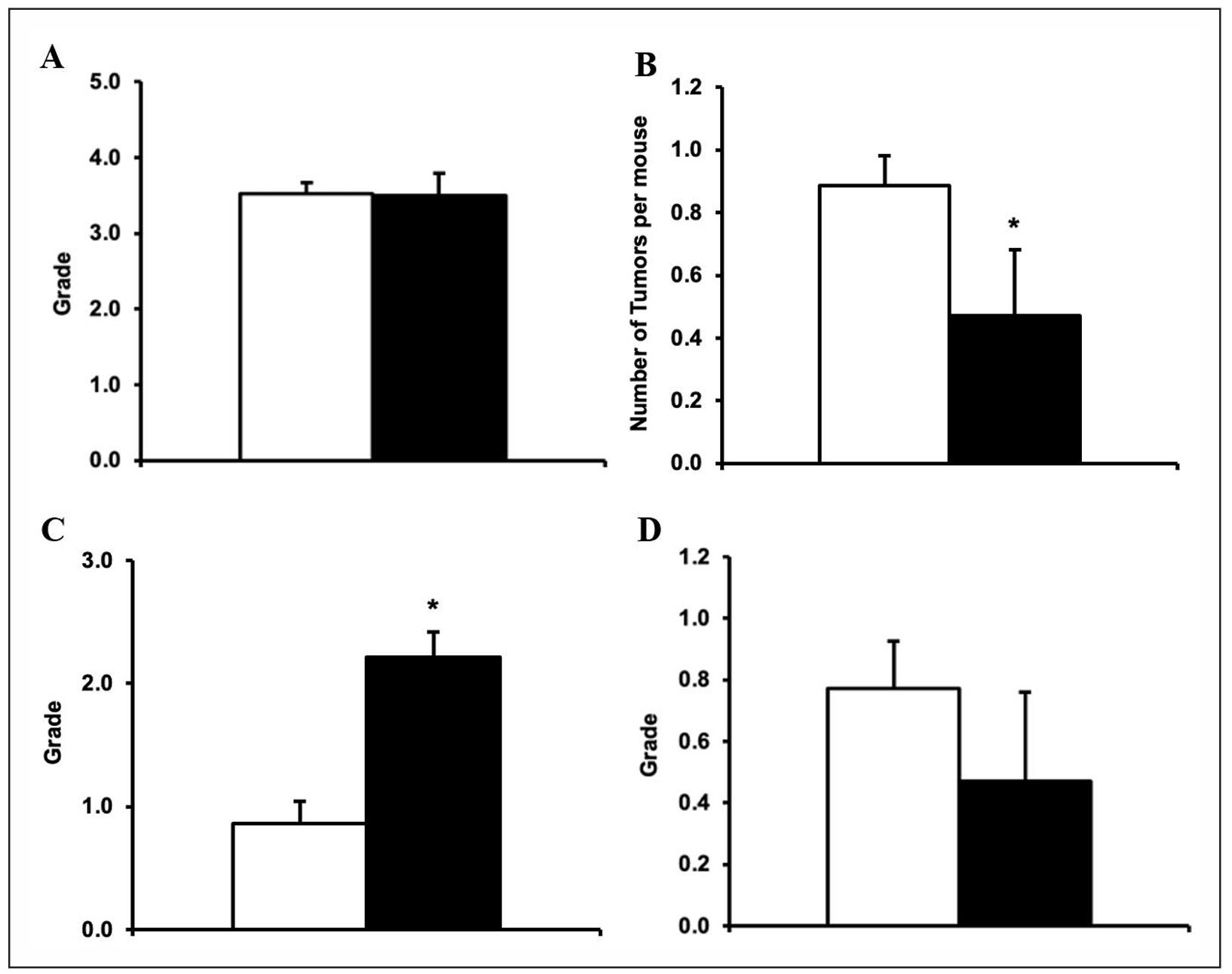

The end-of-life pathology data were collected from male quadruple Msr KO and WT mice. The probable cause of death is presented in Table 3. Approximately 29% of quadruple Msr KO mice and 64% of WT mice developed fatal neoplastic diseases, with lymphoma being the major disease. The incidence of fatal tumors in male quadruple Msr KO mice (29.4%) was significantly less than WT mice (63.6%) (P = 0.0162). The incidence of fatal lymphoma in male quadruple Msr KO mice (29.4%) was significantly less than WT mice (59.1%) (P = 0.0376). However, the severity of lymphoma was similar between male quadruple Msr KO and WT mice (Figure 2a; P > 0.05). The tumor burden (number of total neoplastic lesions per mouse) of male quadruple Msr KO mice (0.47) was significantly lower than WT mice (0.89) (Figure 2b; P = 0.032).

Table 3.

Probable cause of death in male Msr KO mice.

| WT | Msr KO | |

|---|---|---|

| Neoplasm | 27 | 5 |

| Lymphoma | 24 | 5 |

| Lymphoma + other tumors | 1 | 0 |

| Other tumors | 2 | 0 |

| Non-neoplasm | 16 | 8 |

| Glomerulonephritis | 1 | 2 |

| Acidophilic macrophage pneumonia | 0 | 1 |

| Others | 2 | 0 |

| Undetermined | 13 | 5 |

| Neoplasm + Non-neoplasm | 1 | 0 |

| Autolysis | 0 | 9 |

| Total | 44 | 17 |

The incidence of fatal glomerulonephritis, a major agerelated non-neoplastic lesion in C57BL/6 mice, was similar between male quadruple Msr KO and WT mice (P > 0.05); however, the severity of glomerulonephritis was significantly higher in male quadruple Msr KO mice (2.22) compared to WT mice (0.86) (Figure 2c; P < 0.01). The comorbidity index, which is the total number of diseases detected per mouse was slightly less in male quadruple Msr KO mice compared to WT mice; however, it was not statistically significant (Figure 2d; P = 0.071).

Figure 2. The severity of lymphoma, tumor burden, severity of glomerulonephritis, and comorbidity index in male quadruple Msr KO and WT mice. The end-of-life pathology data were collected from male quadruple Msr KO and WT mice. The severity of lymphoma (Figure 2a: top left), tumor burden (Figure 2b: top right), severity of glomerulonephritis (Figure 2c: bottom left), and comorbidity index (Figure 2d: bottom right) in quadruple Msr KO (closed bar) and WT (open bar) were compared. The severity of lymphoma was similar in quadruple Msr KO compared to the WT mice. The tumor burden (number of total neoplastic lesions per mouse) of quadruple Msr KO (0.47) mice was significantly lower than WT mice (0.89) (Figure 2b; *P = 0.032). The severity of glomerulonephritis was significantly higher in quadruple Msr KO mice (2.22) compared to WT mice (0.86) (Figure 2c; *P < 0.01). The comorbidity index (the total number of diseases detected per mouse) was slightly less in male quadruple Msr KO mice compared to WT mice (P = 0.071).

Therefore, the pathology data shown in Table 3 and Figure 2 convincingly demonstrate that the loss of four Msrs has significant benefits by suppressing cancer development during aging in male mice. However, these benefits are accompanied by significantly deleterious effects on a major non-neoplastic lesion, i.e., glomerulonephritis, compared to WT mice.

Discussion

The free radical theory, currently known as the oxidative stress theory, has been one of the most popular theories in aging over the past several decades because the accumulation of oxidative damage to macromolecules and cellular components could cause cellular/physiological dysfunction and functional decline leading to aging and age-related diseases [2, 39-46]. To directly test the causal roles of oxidative stress and damages in aging and agerelated diseases, several laboratories, including ours, have conducted the aging study using mice that genetically altered various components of the antioxidant defense system. Richardson et al. have extensively examined the role of oxidative stress on aging with various mouse models by up-regulating or down-regulating major antioxidant enzymes [8-10]. Although these transgenic and KO mice showed some interesting changes, e.g., changes in oxidative damage to macromolecules, mitochondrial function, cellular functions, and response to oxidative stress, etc., no significant differences in lifespans were observed. There were a couple of exceptions: a) the mice overexpressing catalase in mitochondria (MCAT mice) showed significantly extended lifespan and reduced some of the age-related pathology compared to WT littermates [11]; and b) the mice that lack Cu/ZnSOD (Cu/ZnSOD null mice) had a significantly shorter lifespan and were associated with an increased occurrence of hepatocellular carcinoma, which is an uncommon neoplastic lesion in C57BL/6 mice [12]. Despite these interesting outcomes with MCAT and Cu/ZnSOD null mice, studies with mice that have altered levels of major antioxidant enzymes did not support the oxidative stress theory of aging. Since protecting macromolecules against oxidative damages may not be sufficient to have significant biological effects on aging and pathobiology, the research in this field (oxidative stress and aging) has shifted to seek the molecules that possess not only antioxidant properties, but also have diverse pathophysiological effects by changing the gene expression and protein/enzymes functions.

Although all macromolecules can be damaged by ROS, a large portion (50-75%) of ROS could be scavenged by proteins [47]. Interactions between ROS and proteins could cause a wide range of post-translational modifications depending on the number of the sites with side chains and backbones, and degree of modifications. The current consensus is that: a) reversible modifications of protein could play important roles in redox signaling, which is involved in physiological cellular functions; and b) irreversible modifications of proteins could lead to the loss of function and/or development of potential toxic effects, which may be involved as pathogenesis in various diseases. The major targets of ROS in proteins are the sulfur-containing amino acids: methionine and cysteine, and these amino acids are most susceptible to oxidation [47]. Methionine oxidation turns methionine to methionine sulfoxide leading to structural and functional changes of proteins. This oxidation process can be reversed by Msr [14]. This high susceptibility to oxidation and catalytic reaction that reduces methionine sulfoxide back to methionine, makes methionine a very unique molecule in cellular function and aging. These oxidation-reduction reactions could not only protect other amino acids and proteins from oxidative damage by scavenging ROS, but also play important roles in protein functions as the initiation of protein synthesis, maintaining protein structure, and redox regulation. These critical biological roles of methionine could be possible because of Msr, which reduces methionine sulfoxide (oxidized methionine) back to methionine. There are two main isoforms of Msr: MsrA and MsrB, which has three subclasses in mammals (MsrB 1-3) [19-21].

Studies with MsrA KO mice exhibited enhanced tissue/ organ damages under several experimental conditions. MsrA KO mice showed increased sensitivity to paraquat and cisplatin, severe ischemia-reperfusion damage to kidney and brain, higher hepatotoxicity by acetaminophen, and progressive hearing loss [22-30]. The studies with MsrB KO mice showed increased oxidative damage to lipids and proteins, and oxidized glutathione in both liver and kidneys; however, prominent tissue and organ damages, except hearing loss, were not observed in MsrB KO mice [48]. An aging study with MsrA KO mice showed that their lifespan was similar to the WT control, despite the increased sensitivity to oxidative stress [22]. These results led us to question whether the loss of one Msr protein may not be sufficient to have a significant impact on longevity, i.e., synergistic effects by all four isoforms of Msr deletion may be required to have age-related pathophysiological changes. The mouse lacking MsrA, MsrB1, MsrB2, and MsrB3 (quadruple Msr KO mouse) was generated to examine whether the four isoforms of Msr have synergistic and significant effects against oxidative stress, changes in redox signaling pathways, and pathobiology [31]. The initial characterization showed that quadruple Msr KO mice did not have any developmental abnormalities, showed normal post-natal growth, and were fertile. On the contrary to the initial expectations that these mice would be more sensitive to oxidative stress, quadruple Msr KO mice were more resistant to oxidative stresses induced by ischemic-reperfusion in the heart or intraperitoneal paraquat injection. With this very unique mouse model, we investigated the effects of the loss of four Msrs on aging by conducting the survival study and examining the end-of-life pathology using male quadruple Msr KO mice.

Our survival study showed that the survival curve of male quadruple Msr KO mice was slightly different from WT mice, with a P-value that was marginal to statistical significance. The mean, median, and 10th percentile lifespans of male quadruple Msr KO mice were approximately 3%, 4%, and 16% shorter than the WT mice, respectively. Despite the general trends that male quadruple Msr KO mice had a slightly shorter lifespan, no significant changes in lifespan analyses were observed in the log rank test for the survival curve analyses, and mean, median, and 10th percentile lifespans. This study was conducted with a small number of male quadruple Msr KO mice because of their high neonatal deaths (approximately 40% less survival of pups until weaning than WT mice). Therefore, it would be of interest to analyze the survival data including perinatal/ neonatal deaths, since human population studies analyze the data incorporating neonatal deaths.

The end-of-life pathological analyses were conducted with male quadruple Msr KO mice. Approximately 64% of WT and 29% of quadruple Msr KO mice had neoplastic diseases, and lymphoma was the major neoplastic lesion. The incidence of fatal lymphoma in male quadruple Msr KO mice was significantly less (29.4%) than WT mice (59.1%), although the average severity of lymphoma was similar between male quadruple Msr KO and WT mice. The incidence of fatal tumors (all types of tumors) in male quadruple Msr KO mice was significantly less (29.4%) than WT mice (63.6%). The tumor burden of male quadruple Msr KO mice (0.47) was significantly lower than WT mice (0.89). This indicates that the deletion of four Msrs significantly suppressed the spontaneous tumor development during aging. These results were paradoxical because our previous work showed that suppression of spontaneous cancer formation was accompanied by extended lifespans with long-lived mice, while male quadruple Msr KO mice showed suppressed spontaneous cancer development with a slightly shorter lifespan. These paradoxical results are similar to the observations with short-lived Ku70 and Ku80 mice, which also showed less tumor frequency [49]. Several studies conducted to test the role of Msr in cancer development [50-56] showed contradictory results, i.e., Msr showed proor anti-cancer effects, possibly depending on the types of cancer. Thus, to our knowledge, this study is the first to report the protective roles by the deletion of four Msrs on spontaneous tumor development during aging. On the other hand, the pathological analyses showed that the severity of glomerulonephritis, which is one of the major and potential fatal diseases in C57BL/6 mice, was significantly higher in male quadruple Msr KO mice (2.22) compared to WT mice (0.86). This indicates that the loss of four Msrs accelerates the development of some non-neoplastic lesions during aging, which is consistent with the study that showed MsrA deficiency exacerbated kidney damage by lipopolysaccharide in vivo [57].

Our survival and end-of-life pathological analyses showed that the loss of four isoforms of Msr resulted in: a) significant suppression of cancer development; b) deleterious effects on age-related kidney pathology; c) higher neonatal deaths, which led to 40% less survival of pups until weaning; and d) no apparent lifespan changes in male mice. These results urge us to further investigate the pathophysiological roles of the loss of four Msrs in aging and age-related pathology. Among our observations, the most striking anti-cancer effect by the loss of four Msrs in male mice could lead us to seek the underlying mechanisms and the potential discovery of new preventive and/ or therapeutic methods of certain human cancers.

Conclusions

In conclusion, we have conducted survival and end-of-life pathological analyses of mice that lack all four isoforms of Msr (MsrA and MsrB1-3), referred to as quadruple Msr KO mice. Our study demonstrated that the male quadruple Msr KO mice exhibited a significant suppression of cancer development including lymphoma; however, this antitumor effect was accompanied by deleterious changes on kidney pathology. No significant changes in lifespan were observed in male quadruple Msr KO mice. However, the male quadruple Msr KO mice showed higher neonatal deaths, which resulted in a 40% reduction in the survival of pups until weaning. These results urge us to further investigate the underlying mechanisms of pathophysiological roles of the loss of four Msrs in aging and age-related pathology as systemic and comprehensive analyses were not conducted in this study. These results also call for further investigation to seek the underlying mechanisms of anti-cancer effects by the loss of four Msrs, which could lead to the potential discovery of new preventive and/or therapeutic methods for certain human cancers.

Declarations

Acknowledgments

We acknowledge Dr. Rodney Levine for providing the quadruple Msr KO mice for this study, and the Pathology Core and Administrative and Program Enrichment Core of the San Antonio Nathan Shock Center for providing histology works, pathological analyses, and biostatistical support.

Availability of data and materials

Not applicable.

Conflict of interest statement

Yuji Ikeno is a member of the editorial board of Aging Pathobiology and Therapeutics. The authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest or involvement in the journal’s review process or editorial decision regarding the publication of this manuscript.

Financial support and sponsorship

This research was supported by NIH grants: P30AG13319 (San Antonio Nathan Shock Center Pathology Core: Y.I., J.G., and A.S.) and R01AG070034 (Y.I.).

Ethical approval and consent of participate

Not applicable.

References

1. Bokov A, Chaudhuri A, & Richardson A. The role of oxidative damage and stress in aging. Mech Ageing Dev, 2004, 125(10-11): 811-826. [Crossref]

2. Sohal R, & Weindruch R. Oxidative stress, caloric restriction, and aging. Science, 1996, 273(5271): 59-63. [Crossref]

3. Honda Y, & Honda S. The daf-2 gene network for longevity regulates oxidative stress resistance and Mn-superoxide dismutase gene expression in Caenorhabditis elegans. Faseb J, 1999, 13(11): 1385-1393.

4. Ishii N, Goto S, & Hartman P. Protein oxidation during aging of the nematode Caenorhabditis elegans. Free Radic Biol Med, 2002, 33(8): 1021-1025. [Crossref]

5. Liang H, Masoro E, Nelson J, Strong R, McMahan C, & Richardson A. Genetic mouse models of extended lifespan. Exp Gerontol, 2003, 38(11-12): 1353-1364. [Crossref]

6. Murakami S, Salmon A, & Miller R. Multiplex stress resistance in cells from long-lived dwarf mice. Faseb j, 2003, 17(11): 1565-1566. [Crossref]

7. Huang T, Carlson E, Gillespie A, Shi Y, & Epstein C. Ubiquitous overexpression of CuZn superoxide dismutase does not extend life span in mice. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci, 2000, 55(1): B5-9. [Crossref]

8. Pérez V, Van Remmen H, Bokov A, Epstein C, Vijg J, & Richardson A. The overexpression of major antioxidant enzymes does not extend the lifespan of mice. Aging cell, 2009, 8(1): 73-75. [Crossref]

9. Pérez V, Bokov A, Van Remmen H, Mele J, Ran Q, Ikeno Y, et al. Is the oxidative stress theory of aging dead? Biochim Biophys Acta, 2009, 1790(10): 1005-1014. [Crossref]

10. Van Remmen H, Ikeno Y, Hamilton M, Pahlavani M, Wolf N, Thorpe S, et al. Life-long reduction in MnSOD activity results in increased DNA damage and higher incidence of cancer but does not accelerate aging. Physiol Genomics, 2003, 16(1): 29-37. [Crossref]

11. Schriner S, Linford N, Martin G, Treuting P, Ogburn C, Emond M, et al. Extension of murine life span by overexpression of catalase targeted to mitochondria. Science, 2005, 308(5730): 1909-1911. [Crossref]

12. Elchuri S, Oberley T, Qi W, Eisenstein R, Jackson Roberts L, Van Remmen H, et al. CuZnSOD deficiency leads to persistent and widespread oxidative damage and hepatocarcinogenesis later in life. Oncogene, 2005, 24(3): 367-380. [Crossref]

13. Brot N, Weissbach L, Werth J, & Weissbach H. Enzymatic reduction of protein-bound methionine sulfoxide. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA, 1981, 78(4): 2155-2158. [Crossref]

14. Brot N, & Weissbach H. Peptide methionine sulfoxide reductase: biochemistry and physiological role. Biopolymers, 2000, 55(4): 288-296. [Crossref]

15. Levine R, Berlett B, Moskovitz J, Mosoni L, & Stadtman E. Methionine residues may protect proteins from critical oxidative damage. Mech Ageing Dev, 1999, 107(3): 323-332. [Crossref]

16. Levine R, Mosoni L, Berlett B, & Stadtman E. Methionine residues as endogenous antioxidants in proteins. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA, 1996, 93(26): 15036-15040. [Crossref]

17. Kim K, Kim I, Lee K, Rhee S, & Stadtman E. The isolation and purification of a specific "protector" protein which inhibits enzyme inactivation by a thiol/Fe(III)/O2 mixedfunction oxidation system. J Biol Chem, 1988, 263(10): 4704-4711.

18. Valley C, Cembran A, Perlmutter J, Lewis A, Labello N, Gao J, et al. The methionine-aromatic motif plays a unique role in stabilizing protein structure. J Biol Chem, 2012, 287(42): 34979-34991. [Crossref]

19. Weissbach H, Resnick L, & Brot N. Methionine sulfoxide reductases: history and cellular role in protecting against oxidative damage. Biochim Biophys Acta, 2005,1703(2): 203-212. [Crossref]

20. Lee B, Dikiy A, Kim H, & Gladyshev V. Functions and evolution of selenoprotein methionine sulfoxide reductases. Biochim Biophys Acta, 2009, 1790(11): 1471-1477. [Crossref]

21. Boschi-Muller S, Gand A, & Branlant G. The methionine sulfoxide reductases: catalysis and substrate specificities. Arch Biochem Biophys, 2008, 474(2): 266-273. [Crossref]

22. Salmon A, Pérez V, Bokov A, Jernigan A, Kim G, Zhao H, et al. Lack of methionine sulfoxide reductase A in mice increases sensitivity to oxidative stress but does not diminish life span. Faseb j, 2009, 23(10): 3601-3608. [Crossref]

23. Noh M, Kim K, Han S, Kim J, Kim H, & Park K. Methionine sulfoxide reductase A deficiency exacerbates cisplatininduced nephrotoxicity via increased mitochondrial damage and renal cell death. Antioxid Redox Signal, 2017, 27(11): 727-741. [Crossref]

24. Kim J, Choi S, Jung K, Lee E, Kim H, & Park K. Protective role of methionine sulfoxide reductase A against ischemia/reperfusion injury in mouse kidney and its involvement in the regulation of trans-sulfuration pathway.Antioxid Redox Signal, 2013, 18(17): 2241-2250. [Crossref]

25. Gu S, Blokhin I, Wilson K, Dhanesha N, Doddapattar P, Grumbach I, et al. Protein methionine oxidation augments reperfusion injury in acute ischemic stroke. JCI Insight, 2016, 1(7): 86460. [Crossref]

26. Kim J, Noh M, Kim K, Jang H, Kim H, & Park K. Methionine sulfoxide reductase A deficiency exacerbates progression of kidney fibrosis induced by unilateral ureteral obstruction. Free Radic Biol Med, 2015, 89: 201-208. [Crossref]

27. Singh M, Kim K, & Kim H. Methionine sulfoxide reductase A deficiency exacerbates acute liver injury induced by acetaminophen. Biochem Biophys Res Commun ,2017, 484(1): 189-194. [Crossref]

28. Erickson J, Joiner M, Guan X, Kutschke W, Yang J, Oddis C, et al. A dynamic pathway for calcium-independent activation of CaMKII by methionine oxidation. Cell, 2008, 133(3): 462-474. [Crossref]

29. Singh M, Kim K, Kwak G, Baek S, & Kim H. Methionine sulfoxide reductase A protects against lipopolysaccharide-induced septic shock via negative regulation of the proinflammatory responses. Arch Biochem Biophys, 2017, 631: 42-48. [Crossref]

30. Alqudah S, Chertoff M, Durham D, Moskovitz J, Staecker H, & Peppi M. Methionine sulfoxide reductase A knockout mice show progressive hearing loss and sensitivity to acoustic trauma. Audiol Neurootol, 2018, 23(1): 20-31. [Crossref]

31. Lai L, Sun J, Tarafdar S, Liu C, Murphy E, Kim G, et al. Loss of methionine sulfoxide reductases increases resistance to oxidative stress. Free Radic Biol Med, 2019, 145: 374-384. [Crossref]

32. Andersen P, Borgan O, Gill R, & Keiding N (1999). Statistical models based on counting processes, SpringerVerlag New York.

33. Wang C, Li Q, Redden D, Weindruch R, & Allison D. Statistical methods for testing effects on "maximum lifespan". Mech Ageing Dev, 2004, 125(9): 629-632. [Crossref]

34. Bronson R, & Lipman R. Reduction in rate of occurrence of age related lesions in dietary restricted laboratory mice. Growth Dev Aging, 1991, 55(3): 169-184.

35. Ikeno Y, Bronson R, Hubbard G, Lee S, & Bartke A. Delayed occurrence of fatal neoplastic diseases in ames dwarf mice: correlation to extended longevity. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci, 2003, 58(4): 291-296. [Crossref]

36. Ikeno Y, Hubbard G, Lee S, Richardson A, Strong R, Diaz V, et al. Housing density does not influence the longevity effect of calorie restriction. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci, 2005, 60(12): 1510-1517. [Crossref]

37. Ikeno Y, Hubbard G, Lee S, Cortez L, Lew C, Webb C, et al. Reduced incidence and delayed occurrence of fatal neoplastic diseases in growth hormone receptor/binding protein knockout mice. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci, 2009, 64(5): 522-529. [Crossref]

38. Pérez V, Cortez L, Lew C, Rodriguez M, Webb C, Van Remmen H, et al. Thioredoxin 1 overexpression extends mainly the earlier part of life span in mice. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci, 2011, 66(12): 1286-1299. [Crossref]

39. Warner H. Superoxide dismutase, aging, and degenerative disease. Free Radic Biol Med, 1994, 17(3): 249-258. [Crossref]

40. Martin G, Austad S, & Johnson T. Genetic analysis of ageing: role of oxidative damage and environmental stresses. Nature Genetics, 1996, 13(1): 25-34. [Crossref]

41. Sohal R, & Orr W. Relationship between antioxidants, prooxidants, and the aging process. Ann N Y Acad Sci, 1992, 663: 74-84. [Crossref]

42. Bohr V, & Anson R. DNA damage, mutation and fine structure DNA repair in aging. Mutat Res, 1995, 338(16): 25-34. [Crossref]

43. Oliver C, Ahn B, Moerman E, Goldstein S, & Stadtman E. Age-related changes in oxidized proteins. J Biol Chem, 1987, 262(12): 5488-5491. [Crossref]

44. Stadtman E. Biochemical markers of aging. Exp Gerontol, 1988, 23(4-5): 327-347. [Crossref]

45. Stadtman E. Protein oxidation and aging. Science, 1992, 257(5074): 1220-1224. [Crossref]

46. Hamilton M, Guo Z, Fuller C, Van Remmen H, Ward W, Austad S, et al. A reliable assessment of 8-oxo-2-deoxyguanosine levels in nuclear and mitochondrial DNA using the sodium iodide method to isolate DNA. Nucleic Acids Res, 2001, 29(10): 2117-2126. [Crossref]

47. Kehm R, Baldensperger T, Raupbach J, & Höhn A. Protein oxidation Formation mechanisms, detection and relevance as biomarkers in human diseases. Redox Biol, 2021, 42: 101901. [Crossref]

48. Fomenko D, Novoselov S, Natarajan S, Lee B, Koc A, Carlson B, et al. MsrB1 (methionine-R-sulfoxide reductase 1) knock-out mice: roles of MsrB1 in redox regulation and identification of a novel selenoprotein form. J Biol Chem, 2009, 284(9): 5986-5993. [Crossref]

49. Li H, Vogel H, Holcomb V, Gu Y, & Hasty P. Deletion of Ku70, Ku80, or both causes early aging without substantially increased cancer. Mol Cell Biol, 2007, 27(23): 8205-8214. [Crossref]

50. De Luca A, Sanna F, Sallese M, Ruggiero C, Grossi M, Sacchetta P, et al. Methionine sulfoxide reductase A downregulation in human breast cancer cells results in a more aggressive phenotype. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A, 2010, 107(43): 18628-18633. [Crossref]

51. Kwak G, & Kim H. MsrB3 deficiency induces cancer cell apoptosis through p53-independent and ER stressdependent pathways. Arch Biochem Biophys, 2017, 621: 1-5. [Crossref]

52. Cabreiro F, Picot C, Perichon M, Castel J, Friguet B, & Petropoulos I. Overexpression of mitochondrial methionine sulfoxide reductase B2 protects leukemia cells from oxidative stress-induced cell death and protein damage. J Biol Chem, 2008, 283(24): 16673-16681. [Crossref]

53. Chen X, Yang S, Ruan X, Ding H, Wang N, Liu F, et al. MsrB1 promotes proliferation and invasion of colorectal cancer cells via GSK-3β/β-catenin signaling axis. Cell Transplant, 2021, 30: 9636897211053203. [Crossref]

54. He Q, Li H, Meng F, Sun X, Feng X, Chen J, et al. Methionine sulfoxide reductase B1 regulates hepatocellular carcinoma cell proliferation and invasion via the mitogen-activated protein kinase pathway and epithelialmesenchymal transition. Oxid Med Cell Longev, 2018, 2018: 5287971. [Crossref]

55. Ma X, Wang J, Zhao M, Huang H, & Wu J. Increased expression of methionine sulfoxide reductases B3 is associated with poor prognosis in gastric cancer. Oncol Lett, 2019, 18(1): 465-471. [Crossref]

56. He D, Feng H, Sundberg B, Yang J, Powers J, Christian A, et al. Methionine oxidation activates pyruvate kinase M2 to promote pancreatic cancer metastasis. Mol Cell, 2022, 82(16): 3045-3060.e3011. [Crossref]

57. Yang L, Xiao J, Zhang L, Lu Q, Hu B, Liu Y, et al. Methionine sulfoxide reductase A deficiency aggravated ferroptosis in LPS-induced acute kidney injury by inhibiting the AMPK/NRF2 axis and activating the CaMKII/HIF1α pathway. Free Radic Biol Med, 2025, 234: 248-263. [Crossref]