Open Access | Review

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-ShareAlike 4.0 International License.

Heart rate recovery under healthy aging or age-related pathologies

* Corresponding author: Anton R. Kiselev

Mailing address: Coordinating Center for Fundamental Research, National Medical Research Center for Therapy and Preventive Medicine, Moscow 101990, Russia.

Email: antonkis@list.ru

Received: 17 September 2025 / Revised: 10 October 2025 / Accepted: 10 December 2025 / Published: 30 December 2025

DOI: 10.31491/APT.2025.12.192

Abstract

The interpretation of heart rate recovery (HRR) in aging presents a paradox: while it is a powerful predictor of mortality in disease states, its decline is not an inevitable consequence of healthy aging. This narrative review critically synthesizes evidence to resolve this paradox by delineating the distinct trajectories of HRR across the aging spectrum. Age alone does not impair HRR following exercise stress. Training status emerges as a more significant determinant of HRR than age. Moreover, HRR following cognitive challenge appears to be preserved with age. Better post-stress HRR predicts superior memory performance in older adults. We conclude that HRR serves not as a simple biomarker of chronological age, but as an integrative marker of physiological reserve, with its prognostic power becoming paramount in the context of age-related disease, and its modifiability offering a key target for interventions.

Keywords

Heart rate recovery, autonomic regulation, cardiovascular aging

Introduction

Heart rate recovery (HRR), the decline in heart rate following exercise cessation, serves as a noninvasive marker of autonomic function and cardiovascular fitness [1-3]. Its prognostic value for all-cause and cardiovascular mortality is well-established [4-13], yet its specific role in differentiating physiological aging from age-related pathology remains less clearly synthesized. Physical exercise leads to a decrease in parasympathetic and an increase in sympathetic influences on the cardiovascular system, increasing blood flow to the heart and skeletal muscles. After the cessation of exercise, the return to the initial autonomic status is associated with a significant decrease in heart rate [1]. This is precisely why HRR can serve as a non-invasive method for assessing autonomic nervous system function [1, 3], with slower HRR indicating autonomic dysfunction [3]. In apparently healthy adults, HRR demonstrates significant correlations with arterial stiffness measures and adds predictive value to clinical variables during exercise testing [14]. Normative data from physically active men shows mean HRR values of 15.2 ± 8.4 bpm at 1 minute and 64.6 ± 12.2 bpm at 3 minutes postexercise, with significant correlations between peak VO2 and 3-minute HRR [15]. In healthy children and adolescents, HRR parameters are inversely associated with metabolic risk factors including waist circumference, systolic blood pressure, triglycerides, and C-reactive protein levels, suggesting a link between metabolic health and autonomic nervous system function from young ages [16]. Indices of obesity, especially body mass index in men and waist-to-hip ratio in women, are associated with heart rate recovery in healthy, non-obese adults [17]. These findings support HRR as a valuable clinical assessment tool across age groups.

The primary objective of this narrative review is to critically synthesize the existing literature on HRR in the context of aging. We aim to: (i) delineate the physiological mechanisms underpinning HRR and the challenges in its measurement; (ii) contrast HRR trajectories in healthy versus pathological aging; and (iii) evaluate its value across a spectrum of age-related diseases.

Methods of literature search

This narrative review was conducted by searching the PubMed and Scopus electronic databases for relevant articles. The search strategy utilized a combination of the following keywords and MeSH terms: “heart rate recovery”, “aging”, “aged”, “autonomic nervous system”, “cardiovascular diseases”, “neurodegenerative diseases”, “sarcopenia”, “diabetes mellitus”, “prognosis”, and “exercise therapy”. The reference lists of retrieved articles were also screened for additional relevant publications. Articles were selected based on their relevance to the objectives of this review, with a focus on human studies, clinical trials, meta-analyses, and significant observational cohorts.

Physiological basis of HRR

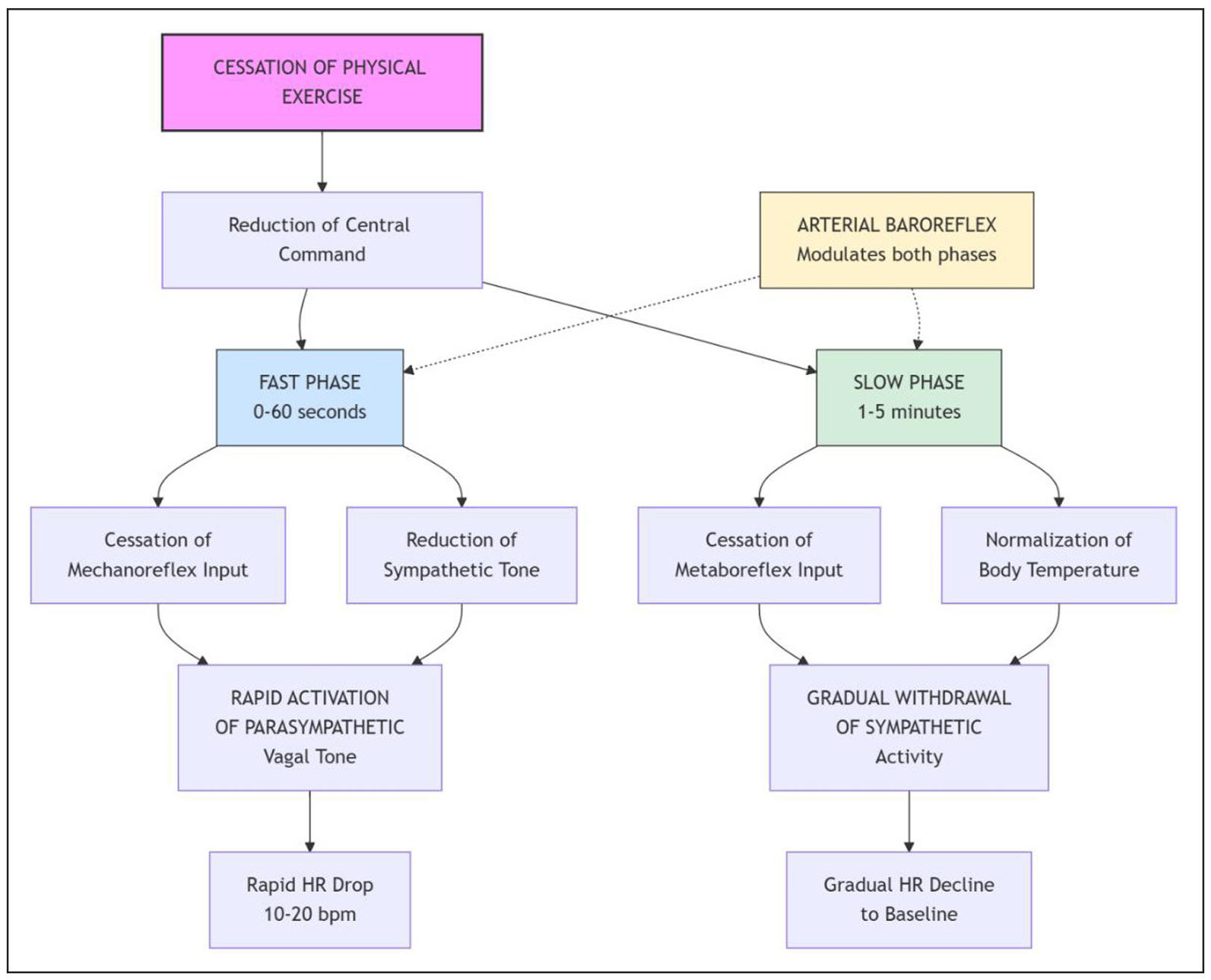

The physiological basis of HRR involves a biphasic exponential decay pattern, with the fast component is characterized by abrupt heart rate decline immediately after exercise cessation, primarily driven by cardiac parasympathetic reactivation through deactivation of central command and mechanoreflex inputs, while the slow phase reflects cardiac sympathetic withdrawal via metaboreflex and thermoregulatory mechanism deactivation [18, 19]. Cardiac parasympathetic activity represents a major contributor to heart rate variability, which underlies HRR mechanisms [20]. The initial, rapid phase of HRR (typically the first 30-60 seconds post-exercise) is predominantly mediated by the swift reactivation of cardiac parasympathetic (vagal) tone. This is triggered by the deactivation of central command from the brain and the reduction in afferent signals from muscle mechanoreceptors. The subsequent, slower phase of HRR reflects the gradual withdrawal of sympathetic nervous system activity, influenced by the lingering effects of metabolites (metaboreflex) and the body’s thermoregulatory processes. The arterial baroreflex also plays a crucial modulatory role in re-establishing autonomic balance and blood pressure homeostasis during recovery. The integrated autonomic pathways mediating HRR are illustrated in Figure 1. Interestingly, faster HRR does not always indicate better physical performance. In endurance athletes developing functional overreaching, HRR increases significantly (+8 ± 5 bpm) despite performance decrements, likely due to decreased central command and lower chemoreflex activity [21]. This paradoxical response occurs across various exercise intensities, with the most discriminant changes observed at submaximal intensities (11-12 km/h) rather than maximal exercise [22]. This highlights that HRR interpretation is context-dependent and must be integrated with other clinical and performance metrics.

Figure 1. The biphasic neuro-autonomic regulation of HRR after exercise cessation. The schematic illustrates the primary autonomic nervous system pathways that mediate the two-phase decay of heart rate after exercise. The immediate fast phase (0-60 seconds, blue) is predominantly driven by the swift reactivation of cardiac parasympathetic (vagal) tone, triggered by the deactivation of central motor command from the brain and reduced afferent signals from muscle mechanoreceptors. The subsequent slow phase (1-5 minutes, green) reflects the gradual withdrawal of sympathetic nervous system activity, influenced by the lingering effects of muscle metabolites and thermoregulatory processes. The arterial baroreflex (yellow) continuously modulates both phases to re-establish blood pressure homeostasis. HRR, heart rate recovery; HR, heart rate.

Impaired slow HRR is associated with abnormal autonomic function, specifically attenuated vagal reactivation and prolonged sympathetic stimulation after exercise cessation [23]. Slow HRR serves as a powerful predictor of cardiovascular and all-cause mortality [18, 23]. Risk factors for developing slow HRR include obesity, smoking, low education, elevated fasting glucose, hypertension, and physical inactivity [24]. HRR naturally declines with aging, with slow HRR developing in approximately 5% of healthy adults over 20 years [24].

Since it was known that earlier studies had found an association between higher vagal nerve activity and reduced mortality, it was later suggested that this might be the mechanism by which HRR can predict mortality [4]. Later studies [25] confirmed that HRR, mediated by vagal nerve reactivation, is an indicator of parasympathetic function, with dysfunction (slower HRR) being associated with increased mortality [6], and faster HRR being associated with reduced mortality [26].

Definition of HRR

HRR is commonly measured as the decline in heart rate from peak exercise to a specified recovery time point, typically expressed as the difference between peak and recovery heart rates [27]. Most researchers specifically defined HRR as the difference between peak exercise heart rate and heart rate one minute later, and this value is reported as an absolute number, for example, 12 beats per minute, with abnormal values defined as ≤ 12 beats per minute reduction [4] or ≤ 18 beats per minute in some protocols [26].

This definition has been used throughout the literature with a minor modification introduced by Shetler et al. [2], who defined it as peak heart rate minus heart rate at a selected time period after exercise cessation. This changed the period during which HRR was measured to 30 s–10 min [28, 29]. Most studies recorded HRR at 1 minute (HRR1) or HRR at 2 minutes (HRR2) after exercise cessation, as there is currently no standardized time interval or threshold value.

Several studies used both cutoff values for HRR1, at either 12 or 18 beats per minute, depending on which exercise test was administered to the patients. Those who underwent standard exercise tests often used the 12 beats per minute cutoff, while exercise echocardiography tests tended to use the 18 beats per minute cutoff [2, 30]. One explanation may be that exercise echocardiography tests did not utilize active recovery; instead, patients lay in a supine position, which may account for the differences in thresholds [31].

HRR2 is the second most commonly used time point. Shetler et al. [2] first suggested that a threshold of 22 beats per minute is clinically superior to other time periods, such as HRR1. This conclusion was later supported by other researchers [32, 33]. Further research involved the use of various threshold values based on statistical tests, such as receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curve analysis. In the study by Lipinski et al. [34], different cut-off points were noted depending on the presence of heart failure or left ventricular systolic dysfunction, and on whether the participants were taking beta-blockers.

HRR after exercise is significantly influenced by exercise modality. Maeder et al. demonstrated that HRR1 was faster following cycle ergometer exercise compared to treadmill exercise in both healthy subjects and heart failure patients, despite lower peak oxygen consumption during cycling [35]. Similarly, Ranadive et al. found that HRR1 following maximal arm ergometry was significantly higher than after leg ergometry, potentially due to greater vagal reactivation following upper body exercise. Training specificity also affects recovery patterns [36]. McDonald et al. showed that anaerobically trained track cyclists had significantly greater heart rate drops at minute two compared to aerobically trained road cyclists, suggesting training mode influences post-exercise autonomic recovery [37]. The lack of standardized HRR measurement protocols presents a significant challenge for clinical interpretation and cross-study comparisons. Adabag and Pierpont surveyed 74 studies and found that 72% used treadmill protocols while 25% used cycle ergometry, emphasizing the need for uniform standards given the significant differences in HRR between exercise modes [38]. One recent study investigated whether HRR would have prognostic value in the 6-minute walk test (a test of functional capacity); the authors found that the predictive accuracy of HRR after the walk test was comparable to that of cardiopulmonary exercise testing in patients with heart failure [39]. This suggests that simpler, more accessible tests could be leveraged for risk stratification in elderly or frail populations, though further validation is needed.

Age-related HRR trajectories

The pattern of age-related HRR decline varies significantly among individuals. Our analysis reveals three distinct trajectories: successful aging with preserved autonomic function, usual aging with moderate decline, and pathological aging characterized by accelerated impairment below clinical thresholds.

HRR and healthy aging

In the general population, we typically observe an agerelated decline in HRR among healthy individuals without major comorbidities [7, 24]. This pattern is referred to as “usual aging with moderate decline”. However, in subgroups of healthy persons with high fitness levels and absence of comorbidities, we observe improved HRR with training, which is considered a marker of “successful aging with preserved autonomic function”.

While HRR from exercise stress typically declines with age due to slower sympathetic withdrawal [40, 41], HRR from cognitive stress appears preserved across age groups [42]. This dissociation implies that the age-related decline is not a universal autonomic deficit but may be specific to the cardiovascular system’s response to physical stress. Age-related decline in HRR correlates with reduced cardiac autonomic function, particularly affecting recovery dynamics 45-210 seconds post-exercise [41]. Importantly, increased habitual physical activity does not appear to attenuate age-related HRR decline [40]. However, structured exercise training programs can improve HRR in older adults, suggesting that specific interventions may enhance vagal tone and cardiovascular capacity [43]. Moreover, these training in elderly can improve HRR to levels exceeding younger controls [43]. This presents a paradox: while general activity may not prevent decline, targeted training can reverse it, highlighting the importance of exercise intensity and structure. Training status appears more influential than age alone on HRR, as trained individuals demonstrate faster recovery regardless of age, while untrained subjects show slower recovery [44]. Elite athletes show age-related differences in HRR, but high fitness may buffer decline [45]. This underscores that functional capacity is a stronger determinant of autonomic health than chronological age.

Several researchers emphasize gender differences in individuals who are not professional athletes. In particular, in healthy women, higher fitness or activity has limited effect on age-related HRR decline [40], but sedentary status is associated with slower HRR [41].

Beyond cardiovascular implications, HRR has cognitive relevance older adults with better post-exercise heart rate recovery perform significantly better on memory tasks compared to those with poor recovery, suggesting cardiac regulation may influence cognitive function [46]. This introduces the concept of a “cardio-cognitive axis” where autonomic integrity may support brain health. These findings highlight HRR as a modifiable factor potentially benefiting both cardiovascular and cognitive health in aging populations. These findings highlight the importance of targeted exercise interventions for maintaining cardiac autonomic function during healthy aging.

HRR after exercise is significantly impacted also by menopause and aging in women. Postmenopausal women demonstrate significantly higher HRR compared to premenopausal women, with both aging and declined estrogen levels contributing to these changes [47]. However, postmenopausal women show attenuated heart rate variability recovery after exercise, indicating delayed autonomic recovery despite similar heart rates to premenopausal women [48]. Estrogen therapy does not restore baseline heart rate variability or accelerate recovery, suggesting aging rather than estrogen deficiency primarily affects these parameters [48]. HRR serves as a sensitive indicator of physical capacity changes, with even slight reductions in physical activity (~16%) resulting in slower recovery rates in perimenopausal and postmenopausal women [49]. Research indicates that aging effects on HRR correlate with slower sympathetic withdrawal, while estradiol levels show moderate correlation with HRR dynamics [41]. And although data on the association between the age at menopause onset and the development of chronic diseases vary somewhat [50-52], this factor may well influence changes in HRR during aging both independently (as discussed above) and through comorbidities.

HRR and age-related diseases

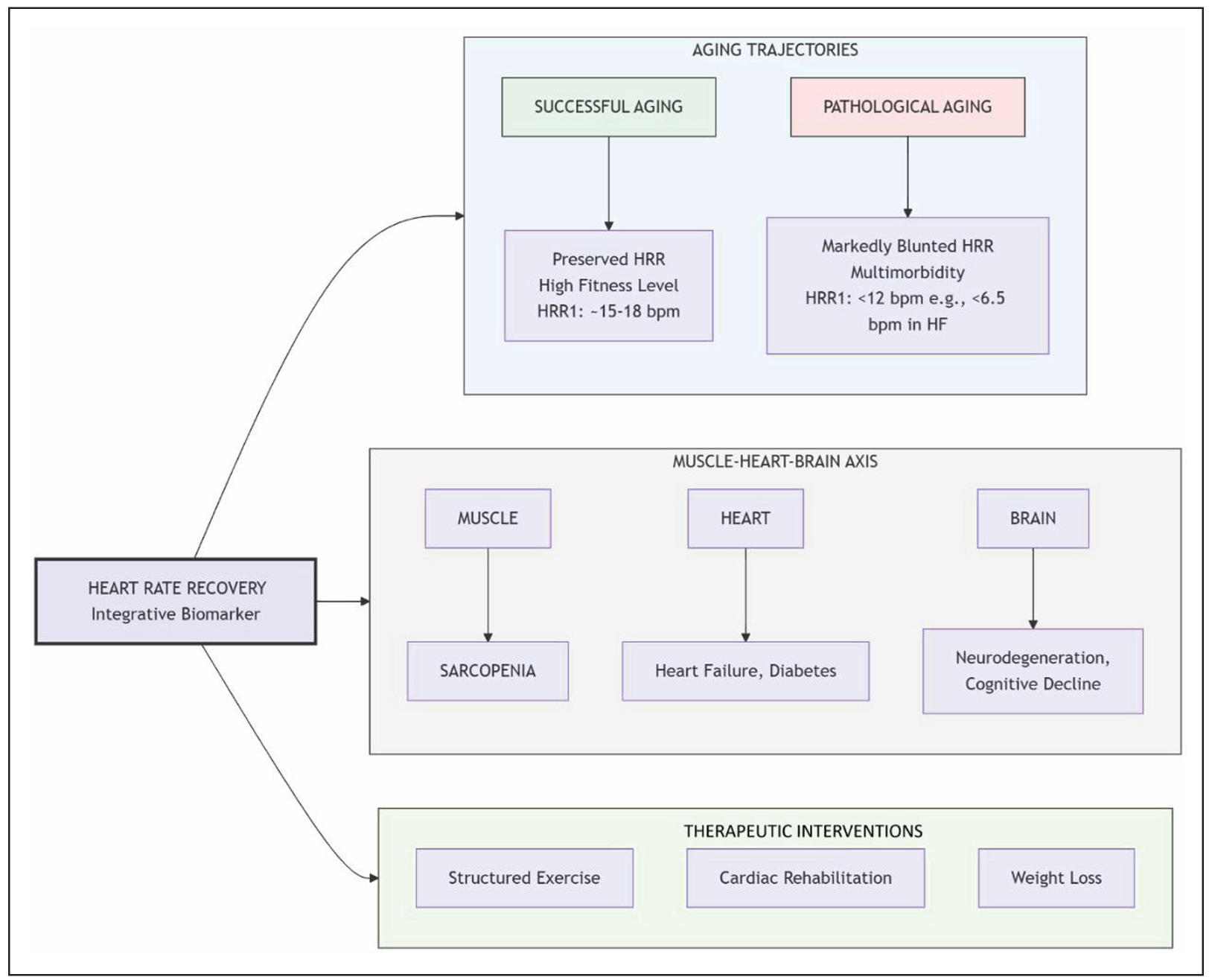

The value of HRR becomes most apparent in the context of age-related diseases, where it serves as a powerful integrator of overall physiological reserve and autonomic burden. This specific group exhibits HRR patterns characteristic of pathological aging. We will now turn to a discussion of HRR alterations in various age-related diseases. The central role of HRR as an integrator of pathological aging across multiple systems is conceptualized in Figure 2.

Figure 2. THRR as a biomarker of physiological reserve and pathological burden in aging. This conceptual model positions HRR as a central integrator of physiological status across the aging spectrum. It outlines three distinct aging trajectories: successful aging (green) with preserved HRR linked to high fitness, versus pathological aging (red) with blunted HRR driven by multimorbidity. The model introduces the muscle-heart-brain axis, illustrating how age-related pathologies in these organ systems (e.g., sarcopenia, heart failure, neurodegeneration) converge to impair autonomic function, reflected in a slower HRR. Finally, it highlights that HRR is a modifiable parameter, with THERAPEUTIC INTERVENTIONS such as structured exercise, cardiac rehabilitation, and weight loss capable of improving autonomic tone and HRR. HRR, heart rate recovery; HRR1, heart rate recovery at 1 minute; HF, heart failure.

Cardiovascular diseases

Physiologically, HRR reflects cardiac parasympathetic reactivation and sympathetic withdrawal, with impaired recovery mechanisms observed in cardiovascular disease patients [18]. A greater impairment in HRR is evident even in older hypertensive patients when compared to age-matched controls exhibiting healthy aging [53].

A comprehensive meta-analysis demonstrated that attenuated HRR is associated with significantly increased risk of cardiovascular events (HR 1.69, 95% CI 1.05-2.71) and all-cause mortality (HR 1.68, 95% CI 1.51-1.88), with each 10 beats per minute decrement in HRR increasing risk by 13% and 9% respectively [54]. The Framingham Heart Study demonstrated that very rapid HRR (top quintile) was associated with lower risk of coronary heart disease and cardiovascular events, but continuous HRR measures showed no significant associations [55]. This suggests a non-linear relationship, where only severely impaired HRR carries significant risk in the general population. Importantly, exercise training can improve HRR in cardiac patients. Both heart failure patients and those undergoing cardiac rehabilitation demonstrated significant improvements in HRR following structured exercise programs [56, 57], suggesting HRR may serve as both a risk stratification tool and outcome measure in clinical practice.

In heart failure patients, HRR provides significant prognostic value beyond traditional exercise parameters, with abnormal HRR (< 6.5 bpm at 1 minute) combined with elevated VE/VCO2 slope conferring a 9.2-fold increased hazard ratio for death/hospitalization [58]. A large retrospective study of 712 heart failure patients demonstrated that HRR independently predicted all-cause mortality over 5.9 years of follow-up, with survival rates declining progressively across HRR groups [59].

Moreover, reduced HRR is linked to poorer cognitive function in older adults with cardiovascular disease, particularly affecting global cognition, executive function, and confrontation naming [60]. This reinforces the cardiocognitive link and positions HRR as a potential marker for identifying cardiovascular disease patients at risk for cognitive decline.

Neurodegenerative diseases

In Parkinson’s disease, patients demonstrate significantly blunted HRR compared to healthy controls, with reduced heart rate decline during recovery from exercise [61]. Prospective data from the UK Biobank reveals that blunted HRR precedes clinical Parkinson’s disease diagnosis by years, with each 10 beats per minute reduction in recovery associated with 30% higher risk of incident Parkinson’s disease [62]. This positions HRR as a potential prodromal biomarker for neurodegeneration, suggesting that autonomic dysfunction is an early feature of the disease process. More broadly, heart rate variability shows moderate positive correlations with cognitive and behavioral performance across neurodegenerative conditions [63]. These findings suggest cardiac autonomic dysfunction, indexed by HRR, may serve as both a prodromal marker and indicator of disease severity in neurodegeneration, though exercise training can improve HRR in other cardiac conditions [57].

Sarcopenia

In male heart failure patients, sarcopenia was associated with reduced heart rate recovery at both 1st and 2nd minutes post-exercise, alongside increased muscle sympathetic nerve activity and decreased parasympathetic reactivation [64]. Community-dwelling elderly adults with sarcopenia exhibited significantly lower parasympatheticassociated heart rate modulation compared to non-sarcopenic individuals, suggesting reduced cardio protection [65]. Long-term heart rate variability monitoring revealed that sarcopenic elderly patients had a fivefold higher risk of reduced heart rate variability, with grip strength showing moderate correlations with some HRV indices [66]. The link between muscle mass/function and autonomic regulation suggests a “muscle-heart-brain” axis that is disrupted in sarcopenia, accelerating pathological aging and contributing to increased cardiovascular risk. While sarcopenia affects blood pressure recovery through cardiac output and peripheral resistance mechanisms, heart rate responses remained unaffected during orthostatic challenges [67]. Thus, the autonomic impairment in sarcopenia may be specific to post-exercise recovery pathways.

Metabolic disorders and type 2 diabetes

Studies show HRR correlates with insulin resistance syndrome components, including reduced insulin sensitivity, altered glucose metabolism, and obesity in elderly men [68].

Among obese older women, higher body fat percentages are associated with significantly impaired HRR and lower peak heart rates during exercise, indicating autonomic dysfunction [69]. Importantly, this relationship is modifiable. A three-month exercise and weight loss program significantly improved HRR in obese participants, with improvements primarily attributed to enhanced cardiopulmonary function rather than metabolic profile changes [70]. This is a key finding, as it demonstrates that HRR improvement can occur independently of metabolic changes, highlighting its role as a dynamic measure of cardiovascular autonomic health. This is particularly interesting given the previously demonstrated absence of differences in resting autonomic status, assessed using classical HRV indices, between obese and nonobese individuals aged 30-60 years without chronic diseases [71]. The contrast between these null findings at rest and the observed dysfunction during exercise suggests that stress testing may be necessary to unmask early autonomic impairment in obesity.

In healthy men, slow HRR is associated with increased risk of developing type 2 diabetes, though this relationship is largely explained by baseline fasting glucose levels [72]. Population-based studies demonstrate that fasting plasma glucose is independently associated with abnormal HRR even at non-diabetic levels, with impaired fasting glucose and diabetes patients showing 34% and 61% higher relative risk of abnormal HRR, respectively [73]. This establishes a continuum of risk, where worsening glucose metabolism progressively impairs autonomic function.

HRR after exercise is significantly impaired in patients with type 2 diabetes and serves as an important prognostic marker. Cataldo et al. demonstrated that sedentary patients with type 2 diabetes have significantly lower HRR compared to healthy controls, with HRR showing a strong correlation with maximal oxygen uptake (r = 0.672) [74]. This impaired recovery has clinical significance, as Chacko et al. found that attenuated HRR predicts all-cause mortality and cardiovascular events in asymptomatic type 2 diabetes patients during 5-year follow-up, with the lowest HRR quintiles showing significantly greater mortality and cardiovascular events [75]. In other study, men with diabetes showed a two-fold increased risk of cardiovascular and all-cause death in the lowest HRR quartile compared to the highest [7]. Additionally, Yamada et al. established that slower HRR can predict silent myocardial ischemia in type 2 diabetes patients, with the silent ischemia group showing significantly slower recovery (18 ± 6 vs. 30 ± 12 bpm) [76]. This makes HRR a valuable noninvasive tool for identifying high-risk diabetic patients who may require more aggressive cardiovascular workup.

Prognostic impact of HRR

A systematic review of 13 prospective cohort studies found that low HRR is directly associated with increased all-cause mortality risk, though the relationship with cardiovascular events showed mixed results [77].

In primary prevention populations, abnormal HRR (< 13 bpm) significantly predicted total, cardiovascular, and non-cardiovascular mortality over 12 years, with hazard ratios of 1.56, 1.95, and 1.41, respectively [13]. In healthy asymptomatic adults, HRR after submaximal exercise was predictive of mortality, with an adjusted attributable risk of 15% [5]. Abnormal HRR identified also a subgroup at intermediate risk despite preserved exercise capacity among patients with stable coronary heart disease [9]. For men with diabetes, HRR at 5 minutes post-exercise was independently predictive of both cardiovascular and allcause mortality, even after adjustment for fitness and other risk factors [7]. Most critically, slower orthostatic HRR strongly predicts mortality risk in individuals aged ≥ 50 years, with each 1-bpm slower recovery increasing mortality hazard by 6% [78].

For all-cause mortality, lower heart rate recovery was associated with higher risk of adverse outcomes [4-7, 8-11, 13, 78]. Adjusted hazard ratios or risk ratios ranged from 1.05 per 1-beat decrease to 2.16 for categorical cutoffs; unadjusted hazard ratios or risk ratios were higher in some studies. One study reported an inverse relationship (hazard ratio < 1 per percent cycle length recovered) [10].

Heterogeneity in measurement protocols and cutoffs, as well as diminished prognostic value in certain subgroups (such as beta-blocker users), should be considered. Nonetheless, HRR establishes itself as an independent predictor of all-cause and cardiovascular mortality. The effect is robust to adjustment for traditional risk factors and exercise capacity, and HRR adds prognostic value beyond other exercise test parameters.

Summary of HRR patterns

In the included studies, successful aging was associated with preserved or improved HRR, often in the context of high fitness or exercise training, even in older age. Usual aging showed a gradual decline in HRR, with demographic and lifestyle factors influencing the trajectory. Pathological aging, marked by comorbidities such as hypertension and other diseases, was associated with further impairment in HRR and increased risk of adverse outcomes.

Therapeutic potential: modifying HRR through intervention

A key question is whether HRR is merely a marker of risk or a modifiable target itself. Evidence strongly supports the latter. In elderly patients recovering from acute myocardial infarction, exercise training improved HRR from 13.5 ± 3.7 to 18.7 ± 3.5 beats/min, with improvements correlating to enhanced cardiopulmonary parameters [79]. Similar HRR improvements were observed in cardiac rehabilitation patients, increasing from 18 ± 7 to 22 ± 8 bpm compared to no change in controls [56].

Exercise training also benefits elderly subjects without cardiac disease, demonstrating HRR improvement alongside enhanced cardiovascular capacity [43]. Importantly, HRR improvements occur regardless of age or gender, with older subjects improving similarly to younger patients during cardiac rehabilitation [80]. Also, higher aerobic fitness levels can partially mitigate age-related decline by preserving post-exercise vagal reentry velocity, and cardiac rehabilitation programs can improve HRR across age groups [80, 81].

As previously discussed, lifestyle interventions in obese individuals also successfully improve HRR [70]. These consistent findings across different populations suggest that improving autonomic function through structured physical activity is a viable therapeutic strategy in aging. However, many questions remain regarding the potential use of HRR as a marker for the effectiveness of physical rehabilitation. For certain groups of older adults, there is virtually no data on the possibility of influencing their autonomic cardiovascular regulation. For example, the significance of autonomic disorders in the pathogenesis of falls syndrome is not clearly understood [82]. This represents a critical gap in knowledge, as frail, fall-prone elders represent a population that could greatly benefit from noninvasive risk stratification.

Limitations

The interpretation of the evidence presented in this review must consider several important limitations. Firstly, the literature on HRR is characterized by a significant heterogeneity in measurement protocols, including the use of different exercise modalities (treadmill vs. cycle ergometer), recovery postures (active vs. passive), and time points for assessment (HRR1, HRR2, etc.). This lack of standardization complicates direct comparison across studies and hinders the establishment of universal threshold values. Secondly, while numerous prospective cohorts demonstrate a strong association between impaired HRR and adverse outcomes, the majority of this evidence is observational. Therefore, a definitive cause-and-effect relationship cannot be established, and residual confounding factors cannot be entirely ruled out. Finally, this review, by its narrative nature, may not have captured every relevant study, and the selection of literature, while systematic in intent, may be subject to author bias.

Conclusions

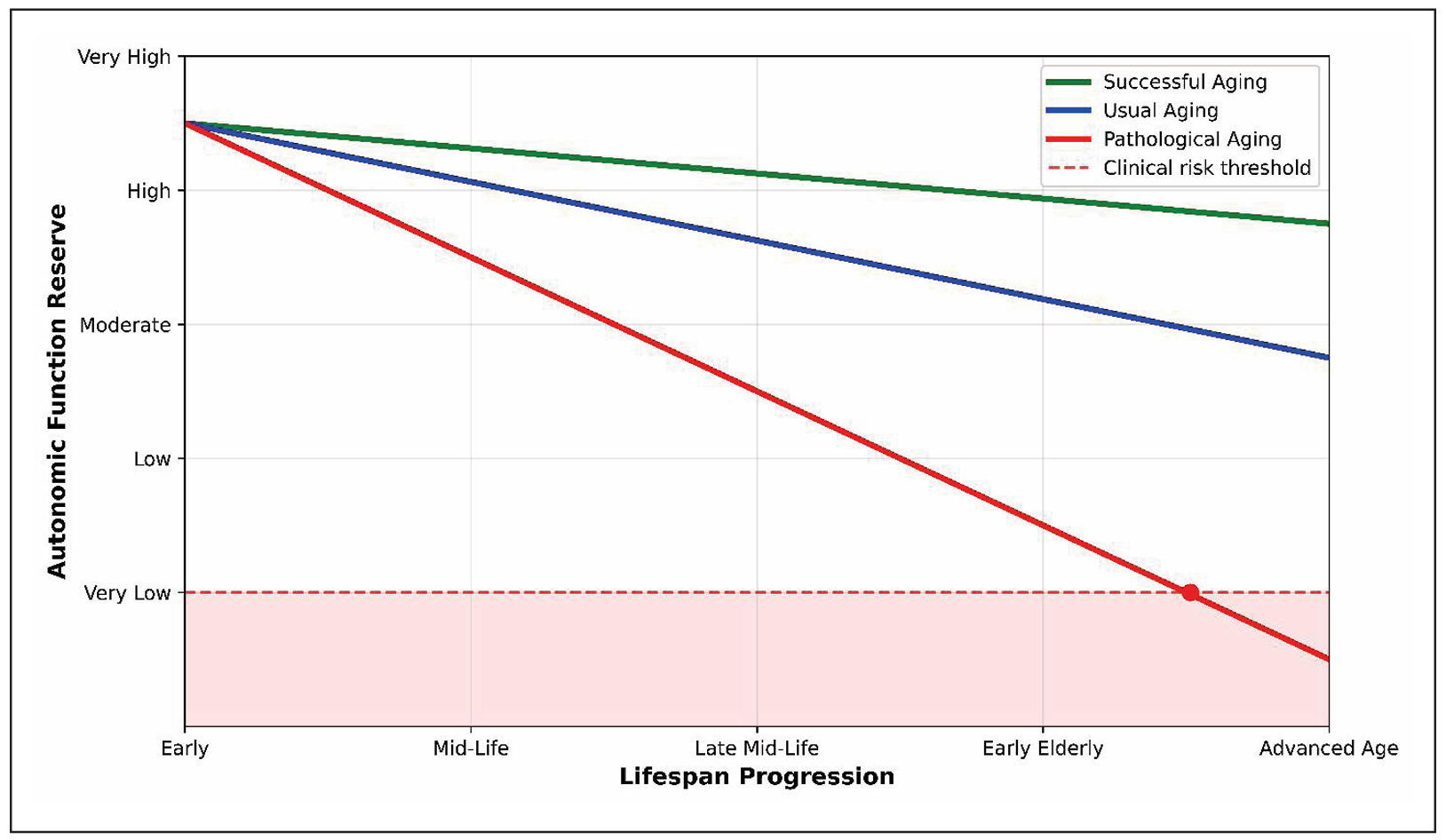

In summary, the evidence synthesized in this review delineates a clear dichotomy in HRR trajectories during aging (Figure 3). Despite the initial impression of a link between HRR and aging, it can still be argued that there is no substantial decline in HRR, provided an active lifestyle and physical and mental fitness are maintained. This may indicate a fairly good chance of preserving the adaptive capacity of autonomic regulation in healthy aging. In this “successful aging” scenario, HRR remains largely preserved, with training status being a more powerful determinant than chronological age. However, the situation changes drastically under the influence of various age-related pathologies, where HRR becomes a significant prognostic marker. In pathological aging, a markedly blunted HRR emerges as a powerful, independent predictor of mortality and morbidity across cardiovascular, metabolic, and neurodegenerative diseases.

Figure 3. Age-related trajectories of HRR decline.

The schematic illustrates three distinct aging patterns in autonomic function reserve: successful aging (green) demonstrates preserved HRR with minimal decline throughout lifespan progression; usual aging (blue) shows moderate HRR decline following expected age-related physiological changes; pathological aging (red) exhibits accelerated HRR impairment, crossing the clinical risk threshold (dashed red line) and entering the high-risk zone (red shaded area). The red circle indicates the critical transition point where pathological HRR decline reaches clinically significant levels, though the exact chronological age of this transition varies among individuals depending on comorbidities, lifestyle factors, and genetic predisposition. Nevertheless, physical rehabilitation can address some of the problems associated with autonomic disorders linked to age-related comorbidity. Crucially, HRR is a modifiable parameter; structured exercise training and lifestyle interventions can improve autonomic tone and HRR, translating to better clinical outcomes. Based on the literature analysis, it is evident that physical fitness with adequate autonomic reactions is a prerequisite not only for healthy aging but also for the rehabilitation of elderly individuals with various age-associated pathologies. A comparative synthesis of the impact of healthy and pathological aging on HRR is presented in Table 1. Future research should focus on standardizing HRR assessment in geriatric populations, exploring its utility in frailty and falls prevention, and investigating its role as a dynamic biomarker in personalized rehabilitation programs.

Table 1.

The Impact of health y aging and age-related diseases on HRR.

| Aspect | Healthy aging | Pathological aging | Clinical and therapeutic implications |

|---|---|---|---|

| HRR change | Minimal decline or preserved [43]. | Significantly and consistently blunted [58, 76]. | A markedly reduced HRR is a red flag for underlying comorbidity and high risk. |

| Primary driver |

Training status > Chronological age [44]. |

Presence and severity of disease (CVD, diabetes, neurodegeneration) [62]. | Focus on maintaining fitness in heal- th; aggressive risk factor management in disease. |

| Prognostic value | Limited as an isolated marker [55]. | Powerful, independent predictor of all-cause and cardiovascular mortality [13]. | Most valuable for risk stratification in patients with established disease. |

| Autonomic contribution | Predominantly slower sympathetic withdrawal [40, 41]. | Combined impairment of vagal reacti- vation and sympathetic withdrawal [23]. | Reflects a more severe and global autonomic dysfunction in disease states. |

| Cognitive link | Preserved. Better HRR predicts superior memory performance [46]. | Impaired. Blunted HRR is associated with poorer executive function and global cognition [60]. | HRR may serve as a non-invasive marker of the cardio-cognitive axis in both health and disease. |

| Response to Intervention | High. Structured training improves HRR [79]. | Moderate but significant. Cardiac rehabilitation and lifestyle changes improve HRR and prognosis [56, 57, 70]. | HRR is a modifiable risk factor. Improvement can be used to monitor intervention efficacy. |

| Example HRR values | HRR1: ~15-18 bpm (in trained individuals) [15]. | HRR1: < 12 bpm (abnormal). e.g., < 6.5 bpm in heart failure [76]. | Each 10-bpm decrement in HRR is associated with a 9% increased risk of death. |

| Therapeutic target | Maintain high physical activity to preserve autonomic tone. | Utilize cardiac rehabilitation to imp- rove prognosis and functional status. | Monitoring HRR can assess intervention efficacy. |

Declarations

Availability of data and materials

Not applicable.

Financial support and sponsorship

None.

Conflicts of interests

Not applicable.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Funding

This study was supported by the Russian Science Foundation (Project No. 24-24-00333).

References

1. Imai K, Sato H, Hori M, Kusuoka H, Ozaki H, Yokoyama H, et al. Vagally mediated heart rate recovery after exercise is accelerated in athletes but blunted in patients with chronic heart failure. J Am Coll Cardiol, 1994, 24(6): 1529-1535. [Crossref]

2. Shetler K, Marcus R, Froelicher V, Vora S, Kalisetti D, Prakash M, et al. Heart rate recovery: validation and methodologic issues. J Am Coll Cardiol, 2001, 38(7): 1980-1987. [Crossref]

3. Buchheit M, Papelier Y, Laursen P, & Ahmaidi S. Noninvasive assessment of cardiac parasympathetic function: postexercise heart rate recovery or heart rate variability? Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol, 2007, 293(1): H8-10. [Crossref]

4. Cole C, Blackstone E, Pashkow F, Snader C, & Lauer M. Heart-rate recovery immediately after exercise as a predictor of mortality. N Engl J Med, 1999, 341(18): 13511357. [Crossref]

5. Cole C, Foody J, Blackstone E, & Lauer M. Heart rate recovery after submaximal exercise testing as a predictor of mortality in a cardiovascularly healthy cohort. Ann Intern Med, 2000, 132(7): 552-555. [Crossref]

6. Nishime E, Cole C, Blackstone E, Pashkow F, & Lauer M. Heart rate recovery and treadmill exercise score as predictors of mortality in patients referred for exercise ECG. JAMA, 2000, 284(11): 1392-1398. [Crossref]

7. Cheng Y, Lauer M, Earnest C, Church T, Kampert J, Gibbons L, et al. Heart rate recovery following maximal exercise testing as a predictor of cardiovascular disease and all-cause mortality in men with diabetes. Diabetes Care, 2003, 26(7): 2052-2057. [Crossref]

8. Myers J, Tan S, Abella J, Aleti V, & Froelicher V. Comparison of the chronotropic response to exercise and heart rate recovery in predicting cardiovascular mortality. Eur J Cardiovasc Prev Rehabil, 2007, 14(2): 215-221. [Crossref]

9. Aijaz B, Squires R, Thomas R, Johnson B, & Allison T. Predictive value of heart rate recovery and peak oxygen consumption for long-term mortality in patients with coronary heart disease. Am J Cardiol, 2009, 103(12): 1641-1646. [Crossref]

10. hnson N, & Goldberger J. Prognostic value of late heart rate recovery after treadmill exercise. Am J Cardiol, 2012, 110(1): 45-49. [Crossref]

11. Dhoble A, Lahr B, Allison T, & Kopecky S. Cardiopulmonary fitness and heart rate recovery as predictors of mortality in a referral population. J Am Heart Assoc, 2014, 3(2): e000559. [Crossref]

12. Lachman S, Terbraak M, Limpens J, Jorstad H, Lucas C, Scholte Op Reimer W, et al. The prognostic value of heart rate recovery in patients with coronary artery disease: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Am Heart J, 2018, 199: 163-169. [Crossref]

13. Sydó N, Sydó T, Gonzalez Carta K, Hussain N, Farooq S, Murphy J, et al. Prognostic performance of heart rate recovery on an exercise test in a primary prevention population. J Am Heart Assoc, 2018, 7(7): 008143. [Crossref]

14. Fei D, Arena R, Arrowood J, & Kraft K. Relationship between arterial stiffness and heart rate recovery in apparently healthy adults. Vasc Health Risk Manag, 2005, 1(1): 85-89. [Crossref]

15. Vicente-Campos D, Martín López A, Nuñez M, & López Chicharro J. Heart rate recovery normality data recorded in response to a maximal exercise test in physically active men. Eur J Appl Physiol, 2014, 114(6): 1123-1128. [Crossref]

16. Lin L, Kuo H, Lai L, Lin J, Tseng C, & Hwang J. Inverse correlation between heart rate recovery and metabolic risks in healthy children and adolescents: insight from the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey 19992002. Diabetes Care, 2008, 31(5): 1015-1020. [Crossref]

17. Dimkpa U, & Oji J. Association of heart rate recovery after exercise with indices of obesity in healthy, non-obese adults. Eur J Appl Physiol, 2010, 108(4): 695-699. [Crossref]

18. Peçanha T, Silva-Júnior N, & Forjaz C. Heart rate recovery: autonomic determinants, methods of assessment and association with mortality and cardiovascular diseases. Clin Physiol Funct Imaging, 2014, 34(5): 327-339. [Crossref]

19. Bartels R, Prodel E, Laterza M, de Lima J, & Peçanha T. Heart rate recovery fast-to-slow phase transition: Influence of physical fitness and exercise intensity. Ann Noninvasive Electrocardiol, 2018, 23(3): e12521. [Crossref]

20. Billman G. The effect of heart rate on the heart rate variability response to autonomic interventions. Front Physiol, 2013, 4: 222-237. [Crossref]

21. Aubry A, Hausswirth C, Louis J, Coutts A, Buchheit M, & Le Meur Y. The development of functional overreaching is associated with a faster heart rate recovery in endurance athletes. PLoS One, 2015, 10(10): e0139754. [Crossref]

22. Le Meur Y, Buchheit M, Aubry A, Coutts A, & Hausswirth C. Assessing overreaching with heart-rate recovery: what is the minimal exercise intensity required? Int J Sports Physiol Perform, 2017, 12(4): 569-573. [Crossref]

23. Davrath L, Akselrod S, Pinhas I, Toledo E, Beck A, Elian D, et al. Evaluation of autonomic function underlying slow postexercise heart rate recovery. Med Sci Sports Exerc, 2006, 38(12): 2095-2101. [Crossref]

24. Carnethon M, Sternfeld B, Liu K, Jacobs D, Jr., Schreiner P, Williams O, et al. Correlates of heart rate recovery over 20 years in a healthy population sample. Med Sci Sports Exerc, 2012, 44(2): 273-279. [Crossref]

25. Yanagisawa S, Miki K, Yasuda N, Hirai T, Suzuki N, & Tanaka T. The prognostic value of treadmill exercise testing in very elderly patients: heart rate recovery as a predictor of mortality in octogenarians. Europace, 2011, 13(1): 114-120. [Crossref]

26. Watanabe J, Thamilarasan M, Blackstone E, Thomas J, & Lauer M. Heart rate recovery immediately after treadmill exercise and left ventricular systolic dysfunction as predictors of mortality: the case of stress echocardiography. Circulation, 2001, 104(16): 1911-1916.

27. Cozgarea A, Cozma D, Teodoru M, Lazăr-Höcher A, Cirin L, Faur-Grigori A, et al. Heart rate recovery: up to date in heart failure-a literature review. J Clin Med, 2024, 13(11): 3328-3341. [Crossref]

28. Nissinen S, Mäkikallio T, Seppänen T, Tapanainen J, Salo M, Tulppo M, et al. Heart rate recovery after exercise as a predictor of mortality among survivors of acute myocardial infarction. Am J Cardiol, 2003, 91(6): 711-714. [Crossref]

29. Sheppard R, Racine N, Roof A, Ducharme A, Blanchet M, & White M. Heart rate recovery-a potential marker of clinical outcomes in heart failure patients receiving betablocker therapy. Can J Cardiol, 2007, 23(14): 1135-1138. [Crossref]

30. Messinger-Rapport B, Pothier Snader C, Blackstone E, Yu D, & Lauer M. Value of exercise capacity and heart rate recovery in older people. J Am Geriatr Soc, 2003, 51(1): 63-68. [Crossref]

31. Vivekananthan D, Blackstone E, Pothier C, & Lauer M. Heart rate recovery after exercise is a predictor of mortality, independent of the angiographic severity of coronary disease. J Am Coll Cardiol, 2003, 42(5): 831-838. [Crossref]

32. Lipinski M, Vetrovec G, & Froelicher V. Importance of the first two minutes of heart rate recovery after exercise treadmill testing in predicting mortality and the presence of coronary artery disease in men. Am J Cardiol, 2004, 93(4): 445-449. [Crossref]

33. Goda A, Koike A, Iwamoto M, Nagayama O, Yamaguchi K, Tajima A, et al. Prognostic value of heart rate profiles during cardiopulmonary exercise testing in patients with cardiac disease. Int Heart J, 2009, 50(1): 59-71. [Crossref]

34. Lipinski M, Vetrovec G, Gorelik D, & Froelicher V. The importance of heart rate recovery in patients with heart failure or left ventricular systolic dysfunction. J Card Fail, 2005, 11(8): 624-630. [Crossref]

35. Maeder M, Ammann P, Rickli H, & Brunner-La Rocca H. Impact of the exercise mode on heart rate recovery after maximal exercise. Eur J Appl Physiol, 2009, 105(2): 247-255. [Crossref]

36. Ranadive S, Fahs C, Yan H, Rossow L, Agiovlasitis S, & Fernhall B. Heart rate recovery following maximal arm and leg-ergometry. Clin Auton Res, 2011, 21(2): 117-120. [Crossref]

37. McDonald K, Grote S, & Shoepe T. Effect of training mode on post-exercise heart rate recovery of trained cyclists. J Hum Kinet, 2014, 41: 43-49. [Crossref]

38. Adabag S, & Pierpont G. Exercise heart rate recovery: analysis of methods and call for standards. Heart, 2013, 99(23): 1711-1712. [Crossref]

39. Cahalin L, Arena R, Labate V, Bandera F, Lavie C, & Guazzi M. Heart rate recovery after the 6 min walk test rather than distance ambulated is a powerful prognostic indicator in heart failure with reduced and preserved ejection fraction: a comparison with cardiopulmonary exercise testing. Eur J Heart Fail, 2013, 15(5): 519-527. [Crossref]

40. Njemanze H, Warren C, Eggett C, MacGowan G, Bates M, Siervo M, et al. Age-related decline in cardiac autonomic function is not attenuated with increased physical activity. Oncotarget, 2016, 7(47): 76390-76397. [Crossref]

41. Beltrame T, Catai A, Rebelo A, Tamburús N, Zuttin R, Takahashi A, et al. Associations between heart rate recovery dynamics with estradiol levels in 20 to 60 yearold sedentary women. Front Physiol, 2018, 9: 533-548. [Crossref]

42. Shcheslavskaya O, Burg M, McKinley P, Schwartz J, Gerin W, Ryff C, et al. Heart rate recovery after cognitive challenge is preserved with age. Psychosom Med, 2010, 72(2): 128-133. [Crossref]

43. Giallauria F, Del Forno D, Pilerci F, De Lorenzo A, Manakos A, Lucci R, et al. Improvement of heart rate recovery after exercise training in older people. J Am Geriatr Soc, 2005, 53(11): 2037-2038. [Crossref]

44. Darr K, Bassett D, Morgan B, & Thomas D. Effects of age and training status on heart rate recovery after peak exercise. Am J Physiol, 1988, 254(2 Pt 2): H340-343. [Crossref]

45. Suzic Lazic J, Dekleva M, Soldatovic I, Leischik R, Suzic S, Radovanovic D, et al. Heart rate recovery in elite athletes: the impact of age and exercise capacity. Clin Physiol Funct Imaging, 2017, 37(2): 117-123. [Crossref]

46. Pearman A, & Lachman M. Heart rate recovery predicts memory performance in older adults. Appl Psychophysiol Biofeedback, 2010, 35(2): 107-114. [Crossref]

47. Vijayalakshmi I, Subha K, & Niruba R. Comparison of cardiac vagal activity between pre and postmenopausal women using heart rate recovery. International Journal of Clinical Trials, 2014, 1(3): 105–109. [Crossref]

48. Harvey P, O’Donnell E, Picton P, Morris B, Notarius C, & Floras J. After-exercise heart rate variability is attenuated in postmenopausal women and unaffected by estrogen therapy. Menopause, 2016, 23(4): 390-395. [Crossref]

49. Zimak B, Tobiasz A, & J M. Heart rate recovery as a sensitive indicator of physical activity changes in perimenopausal and postmenopausal women. Med Rehabil, 2018, 22(2): 11-19. [Crossref]

50. Xu X, Jones M, & Mishra G. Age at natural menopause and development of chronic conditions and multimorbidity: results from an Australian prospective cohort. Hum Reprod, 2020, 35(1): 203-211. [Crossref]

51. Bijani A, Nia F, Hosseini S, & S M. Age at menopause and its association with comorbidities in older women. Russ Open Med J, 2024, 13: e0401. [Crossref]

52. Xing Z, & Kirby R. Age at menopause and multimorbidity in postmenopausal women. Prz Menopauzalny, 2025, 24(1): 1-14. [Crossref]

53. Best S, Bivens T, Dean Palmer M, Boyd K, Melyn Galbreath M, Okada Y, et al. Heart rate recovery after maximal exercise is blunted in hypertensive seniors. J Appl Physiol, 2014, 117(11): 1302-1307. [Crossref]

54. Qiu S, Cai X, Sun Z, Li L, Zuegel M, Steinacker J, et al.Heart rate recovery and risk of cardiovascular events and all-cause mortality: a meta-analysis of prospective cohort studies. J Am Heart Assoc, 2017, 6(5): 005505. [Crossref]

55. Morshedi-Meibodi A, Larson M, Levy D, O’Donnell C, & Vasan R. Heart rate recovery after treadmill exercise testing and risk of cardiovascular disease events (the framingham heart study). Am J Cardiol, 2002, 90(8): 848-852. [Crossref]

56. Tiukinhoy S, Beohar N, & Hsie M. Improvement in heart rate recovery after cardiac rehabilitation. J Cardiopulm Rehabil, 2003, 23(2): 84-87. [Crossref]

57. Myers J, Hadley D, Oswald U, Bruner K, Kottman W, Hsu L, et al. Effects of exercise training on heart rate recovery in patients with chronic heart failure. Am Heart J, 2007, 153(6): 1056-1063. [Crossref]

58. Arena R, Guazzi M, Myers J, & Peberdy M. Prognostic value of heart rate recovery in patients with heart failure. Am Heart J, 2006, 151(4): 851.e857-813. [Crossref]

59. Kubrychtova V, Olson T, Bailey K, Thapa P, Allison T, & Johnson B. Heart rate recovery and prognosis in heart failure patients. Eur J Appl Physiol, 2009, 105(1): 37-45. [Crossref]

60. Keary T, Galioto R, Hughes J, Waechter D, Spitznagel M, Rosneck J, et al. Reduced heart rate recovery is associated with poorer cognitive function in older adults with cardiovascular disease. Cardiovasc Psychiatry Neurol, 2012, 2012: 392490. [Crossref]

61. Sabino-Carvalho J, Guerrero R, Teixeira A, Brandão P, & Vianna L. Cardiac vagal reactivation at the onset of muscle Metaboreflex activation is not further impaired in patients with Parkinson’s disease. Auton Neurosci, 2025, 260: 103311. [Crossref]

62. van Duijvenboden S, Ramírez J, Scheurink J, Darweesh S, Orini M, Tinker A, et al. Heart rate profiles during exercise and incident Parkinson’s disease. Ann Neurol, 2025, 98(5): 1004-1013. [Crossref]

63. Liu K, Elliott T, Knowles M, & Howard R. Heart rate variability in relation to cognition and behavior in neurodegenerative diseases: a systematic review and metaanalysis. Ageing res rev, 2022, 73: 101539. [Crossref]

64. Fonseca G, Santos M, Souza F, Costa M, Haehling S, Takayama L, et al. Sympatho-vagal imbalance is associated with sarcopenia in male patients with heart failure. Arq Bras Cardiol, 2019, 112(6): 739-746. [Crossref]

65. Freitas V, Passos R, Oliveira A, Ribeiro Í J, Freire I, Schettino L, et al. Sarcopenia is associated to an impaired autonomic heart rate modulation in community-dwelling old adults. Arch Gerontol Geriatr, 2018, 76: 120-124. [Crossref]

66. Liu J, & Zhang F. Autonomic nervous system and sarcopenia in elderly patients: insights from long-term heart rate variability monitoring in a hospital setting. Int J Gen Med, 2024, 17: 3467-3477. [Crossref]

67. Duggan E, Knight S, Xue F, & Romero-Ortuno R. Haemodynamic parameters underlying the relationship between sarcopenia and blood pressure recovery on standing. J Clin Med, 2023, 13(1): 18-32. [Crossref]

68. Lind L, & Andrén B. Heart rate recovery after exercise is related to the insulin resistance syndrome and heart rate variability in elderly men. Am Heart J, 2002, 144(4): 666-672. [Crossref]

69. Rocha C, da Cunha Nascimento D, Bicalho L, Tibana R, Saraiva B, Willardson J, et al. Relationship between adiposity and heart rate recovery following an exercise stress test in obese older women. Revista Brasileira de Cineantropometria e Desempenho Humano, 2017, 19:554-569. [Crossref]

70. Nagashima J, Musha H, Takada H, Takagi K, Mita T, Mochida T, et al. Three-month exercise and weight loss program improves heart rate recovery in obese persons along with cardiopulmonary function. J Cardiol, 2010, 56(1): 79-84. [Crossref]

71. Dzhioeva O, Rogozhkina E, Shvarts V, Shvartz E, Kiselev A, & OM D. Indices of heart rate variability are not associated with obesity in patients 30-60 years of age without chronic noncommunicable diseases. Russ Open Med J, 2023, 12(4): e0408. [Crossref]

72. Jae S, Carnethon M, Heffernan K, Fernhall B, Lee M, & Park W. Heart rate recovery after exercise and incidence of type 2 diabetes in men. Clin Auton Res, 2009, 19(3): 189-192. [Crossref]

73. Panzer C, Lauer M, Brieke A, Blackstone E, & Hoogwerf B. Association of fasting plasma glucose with heart rate recovery in healthy adults: a population-based study. Diabetes, 2002, 51(3): 803-807. [Crossref]

74. Cataldo A, Cerasola D, Daniele Z, Proia P, Russo G, Lo Presti R, et al. Heart rate recovery after exercise and maximal oxygen uptake in sedentary patients with type 2 diabetes. J Biol Res, 88(1), 7-8.

75. Chacko K, Bauer T, Dale R, Dixon J, Schrier R, & Estacio R. Heart rate recovery predicts mortality and cardiovascular events in patients with type 2 diabetes. Med Sci Sports Exerc, 2008, 40(2): 288-295. [Crossref]

76. Yamada T, Yoshitama T, Makino K, Lee T, & Saeki F. Heart rate recovery after exercise is a predictor of silent myocardial ischemia in patients with type 2 diabetes. Diabetes Care, 2011, 34(3): 724-726. [Crossref]

77. Michailidou S. Heart rate recovery and risk of cardiovascular disease and all-cause mortality: a systematic review of prospective cohort studies. European Journal of Preventive Cardiology, 2022, 29(Supplement_1): zwac056.135. [Crossref]

78. McCrory C, Berkman L, Nolan H, O’Leary N, Foley M, & Kenny R. Speed of Heart Rate Recovery in Response to Orthostatic Challenge. Circ Res, 2016, 119(5): 666-675. [Crossref]

79. Giallauria F, Lucci R, Pietrosante M, Gargiulo G, De Lorenzo A, D’Agostino M, et al. Exercise-based cardiac rehabilitation improves heart rate recovery in elderly patients after acute myocardial infarction. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci, 2006, 61(7): 713-717. [Crossref]

80. MacMillan J, Davis L, Durham C, & Matteson E. Exercise and heart rate recovery. Heart Lung, 2006, 35(6): 383-390. [Crossref]

81. Trevizani G, Benchimol-Barbosa P, & Nadal J. Effects of age and aerobic fitness on heart rate recovery in adult men. Arq Bras Cardiol, 2012, 99(3): 802-810. [Crossref]

82. Shiryaeva T, Fedotov D, Gribanov A, Krainova I, Bagretsov S, & Preminina O. Features of the relationship between postural balance indicators and heart rate variability in elderly women with falls syndrome. Russian Open Medical Journal, 2024, 13(1): e0102. [Crossref]