Open Access | Research

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-ShareAlike 4.0 International License.

Targeting amyloid aggregation with ethanol extracts of fermented Swietenia macrophylla: a metabolomic and molecular docking approach

* Corresponding author: Muhammad Ajmal Shah

Mailing address: Department of Pharmacy, Hazara University, Mansehra, Pakistan.

Email: ajmalshah@hu.edu.pk

* Corresponding author:Agustina L.N. Aminin

Mailing address:Department Chemistry, Diponegoro University, Semarang City 50275, Indonesia.

Email: agustina.aminin@live.undip.ac.id

Received: 08 September 2025 / Revised: 22 September 2025 / Accepted: 27 October 2025 / Published: 30 December 2025

DOI: 10.31491/APT.2025.12.193

Abstract

Microbial fermentation offers a promising yet underexplored strategy to enhance the anti-amyloidogenic potential of phytochemicals. In particular, the anti-aggregation mechanism of fermented Swietenia macrophylla (mahogany) seed extracts against amyloidogenic proteins has not been comprehensively elucidated. Therefore, this study aimed to evaluate the anti-amyloidogenic potential of mahogany seed extracts fermented with Aspergillus niger (A. niger) using integrated in vitro and in silico approaches. Fermented extracts were analyzed for changes in secondary metabolites and tested for protein aggregation inhibition under thermal and DTT-induced stress using BSA models. LC-MS profiling and molecular docking on Aβ42 were conducted to identify key active compounds and interaction mechanisms. Fermentation significantly elevated triterpenoids (179%), flavonoids (130%), and phenolics (4%), leading to inhibition of BSA aggregation (57.12–79.09%) compared to quercetin (43.24–44.44%). LC-MS identified myricetin, gallocatechin, swietenolide, and swietenine as dominant metabolites. Docking and dynamic simulations revealed that flavonoids (−6.1 to −6.2 kcal/mol) stabilized critical Aβ42 residues (PHE19–ILE31) and reduced residue fluctuations (3.1–4.7 Å), while limonoids contributed to early aggregation inhibition despite higher flexibility (> 6 Å). These findings demonstrate, for the first time, that A. niger fermentation synergistically enhances the anti-amyloidogenic efficacy of mahogany seed metabolites, suggesting their potential as natural neurodegenerative agents against amyloidosis.

Keywords

Anti aggregation, fermented, Swietenia macrophylla, in vitro, in silico

Introduction

With the global rise in neurodegenerative diseases, identifying compounds capable of preventing protein misfolding has become a pressing challenge in aging research [1]. Aging is a complex biological process characterized by progressive cellular and molecular decline, which increases susceptibility to chronic diseases. Among the hallmarks of aging, protein misfolding and aggregation are strongly implicated in neurodegenerative conditions, including Alzheimer’s and Parkinson’s disease [2]. These disorders are associated with the accumulation of amyloid fibrils, β-sheet–rich protein aggregates that disrupt proteostatis and trigger neuronal dysfunction [3]. Although amyloid structures may serve certain physiological roles, their pathological aggregation contributes significantly to agerelated cognitive decline [4].

Model proteins such as bovine serum albumin (BSA) are often used to study protein aggregation due to their wellcharacterized structure and experimental accessibility. BSA tends to form amorphous aggregates under denaturing conditions, providing a convenient platform for screening anti-aggregation activity [5]. Aggregation can be quantitatively assessed using turbidimetric analysis and Congo red assays, the latter of which selectively detects β-sheet amyloid structures [6]. However, BSA as a model protein has limitations, as it does not fully reproduce the pathological β-sheet structures characteristic of neurodegenerative diseases. Therefore, molecular docking and molecular dynamics simulations have proven invaluable in amyloid research, offering insights not only into predicted binding affinities but also into specific molecular interactions. For instance, hydrogen bonding, hydrophobic contacts, and aromatic π–π stacking with fibrilforming residues have been shown to stabilize inhibitory compounds and disrupt fibril elongation, using [7]. In this study, BSA was used for in vitro assays, while β-amyloid fibrils (5OQV) were selected for in silico analysis to ensure both practicality and pathological relevance.

Natural products have long served as a rich source of bioactive compounds with antioxidant, anti-inflammatory, anti-amyloidogenic properties [8]. Recent studies have highlighted limonoids, a subclass of triterpenoids, for antiamyloidogenic potential [9]. Another natural source rich in limonoids is Swietenia macrophylla (mahogany), whose seeds contain triterpenoid derivatives possess strong antioxidant and anti-inflammatory activities, suggesting their potential to stabilize protein structures and mitigate aggregation [10].

Despite this potential, the therapeutic efficacy of plantderived compounds is often limited by low bioavailability and restricted release of bound metabolites. One promising approach to overcome these limitations is microbial fermentation [11]. Fermentation is an effective bioprocessing approach to enhance the bioavailability and concentration of secondary metabolites in plant extracts. Microbial enzymatic activity enables the conversion of complex compounds into simpler and more active forms, thereby improving their pharmacological potential [12]. Previous studies, such as those by Feitosa et al. [11] demonstrated that Aspergillus niger fermentation increased the bioactivity of apricot extracts. Although fermentation has been applied to Swietenia macrophylla substrates using Bacillus Gottheili to increase release of phenolics [13]. Despite extensive reports on the pharmacological potential of mahogany seeds, their anti-amyloidogenic activity, particularly when enhanced through microbial fermentation, remains largely unexplored. Given the wellestablished capacity of A. niger to enhance secondary metabolite activity in other plants, we hypothesize that A. niger fermentation could similarly increase the release and anti-amyloidogenic potential of mahogany seed phytochemicals.

This study investigates the potential of ethanol fractions derived from fermented mahogany seed extracts to counteract amyloidosis induced by reactive agents such as dithiothreitol (DTT) and heat stress. The aggregation process was evaluated using turbidimetry and a Congo red assay on bovine serum albumin protein. The most abundant compounds in the ethanol fraction were identified using liquid chromatography–mass spectrometry, and their potential mechanisms were then investigated in silico. In our previous work [14], we conducted an in-silico study on the anti-aggregation potential of the main compounds from mahogany seeds against BSA protein. Therefore, this study aims to evaluate the anti-amyloidogenic activity of ethanol fractions from fermented mahogany seed extracts through in vitro assays (turbidimetry and Congo red) and in silico analyses (docking and MD against β-amyloid fibrils, PDB 5OQV). By integrating both approaches, we seek to identify candidate anti-aging agents with potential relevance for neurodegenerative disorders.

Materials and methods

Fermentation and extraction Swietenia macrophylla seed

This method was modified from a prior study [11], 20 grams of mahogany seeds were placed into each of three containers, and 100 mL of sterile distilled water was added (moisture content 70%). The mixtures were sterilized for 45 minutes and then inoculated with Aspergillus niger ATCC 9142 was obtained from the Bogor Agricultural Institute (IPB). spore suspension was inoculated at 1% (v/v) of a spore suspension prepared in sterile water; spore concentration of the inoculum was approximately 1.5 × 108 spores/mL. After a 48-hour incubation at 37° Celsius, the fermented mahogany seeds underwent defatting using n-hexane in a 1:1 ratio for 6 hours. The mixture was then filtered, and the residue was dried. Subsequently, the dried residue was extracted using 96% ethanol at a 1:10 ratio maceration for 24 hours. The resulting filtrate was filtered and concentrated using a rotary evaporator to obtain a thick extract as the final sample, Extract yield was 0.05% obtain and the sample called Ethanol Fraction of fermented Swietenia macrophylla (EFFSM).

Metabolite secondary

Total flavonoid content

The total flavonoid test follows the method carried out [15] with minor modifications. EFFSM added 1 mL with 3 mL methanol, 200 μL 2% of AlCl3∙6H2O, 200 μL CH3COONa and the volume is set to 10 mL using aquades, then incubated for 30 minutes at a temperature of 25°C. Absorbance is measured at wavelength 432 nm. Using spectrophotometry UV-VIS, methanol is used as blanks and quercetin is used as standard. The blank consists of all reagents and solvents without sample solution. The quercetin calibration curve is used to determine its content. The results were given as mg Quercetin equivalent (QE)/g dry extract.

Total phenolic content

The total phenol test follows the method performed by [15] with minor modifications. 0.5 mL of EFFSM was added with 2.5 mL of distilled water, 2.5 mL 1N of FolinCiocalteu reagent. Incubated at 25°C for 15 minutes and added 2 mL 5% (w/v) sodium carbonate, incubated at 25°C for 30 minutes, and measured absorbance at 765 nm with UV-VIS spectrophotometer. Methanol is used as the control blank and gallic acid is used as standard. The blank consists of all reagents and solvents without a sample solution. A standard gallic acid calibration curve is used to determine the content. The result was given as mggallic acid equivalent (GAE)/g dry extract.

Total triterpenoid content

This method follows [16] with slight modification, 0.2 mL of EFFSM solution in a 10 mL measuring flask was heated to evaporate in a water bath, 0.5 mL of a new mixture of 5% vanillin-acetate solution (W/V) and 0.9 mL of sulfuric acid was added, mixed and incubated at 70°C for 30 min. Then the mixed solution is cooled and diluted to 5 mL with acetic acid. Absorbance was measured at 573 nm with a UV-VIS spectrophotometry. Methanol is used as a blank, and ursolic acid is used as standard. The blank consists of all reagents and solvents without a sample solution. A standard ursolic acid calibration curve is used to determine the content. The results were given as mg ursolic acid equivalent (UAE)/g dry extract.

In vitro amyloidosis assay

Thermal induced

BSA protein solution 10 mg/mL. Then 1 mL BSA solution added with an EFFSM 0.2 mL of 0.1 mg/mL aquadest as negative control is added and quercetin 100 ppm positive control. Then all samples are heated to 700°C for 45 minutes. After clumping, the sample was measured for absorbance at a wavelength of 600 nm [17].

Induction dithiolteriolriol (DTT)

BSA protein aggregation process induced by DTT. Aggregate formation follows the method [18]. Each mixture contains 20 mM phosphate buffer and 10 mM DTT. The procedure is to add quercetin then incubate at 37°C for 20 hours. The same procedure is applied to the bioactive compound. The turbidity of the BSA protein mixture aggregates with and without inhibitors was measured using a UV-Vis spectrophotometer at a wavelength of 600 nm.

Congo red binding assay

The anti-aggregation assay was performed with slight modifications. This method was use after thermal induced and DTT Induced. 7 mg/mL Congo red solution was freshly prepared in phosphate buffer and filtered using a 0.2 μm syringe filter immediately before use. A volume of 5 μL of the Congo red solution was added to phosphate buffer in a quartz cuvette, and the absorption spectrum was recorded in the range of 400–700 nm as a baseline. Subsequently, 5–10 μL of the protein aggregate solution was added to the cuvette, followed by incubation at room temperature for 30 minutes, during which a visible red precipitate indicated potential amyloid formation. After incubation, the absorption spectrum was recorded again in the same range (400–700 nm). To analyze amyloid fibril formation, the spectrum of Congo red alone was mathematically subtracted from the spectrum of the Congo red mixture. A maximum spectral difference at approximately 540 nm was taken as an indication of amyloid fibril presence.

All measurements were conducted in triplicate (n = 3), and the results were expressed as mean ± standard deviation (SD). Statistical analysis was performed using one-way ANOVA followed by Tukey’s post hoc test, with P < 0.01 considered statistically highly significant, P < 0.05 significant, and while ns considered in significant difference.

Untargeted metabolomic fermented swietenia macrophylla using LCMS

The fermented mahogany sample was diluted with methanol. Soluble extract was then filtered using 0.45-micron Millipore filter. 5 μL filtrate of the sample was injected into the LC-ESI-QTOF system. LC-MS analysis was done by using UPLC-M Equipped with a binary pump. LC is connected to QTOF mass spectrometer coupled to ESI. The MS used was Xevo G2-S QTOF with positive ionization mode. ESI parameters used capillary temperature 120°C, gas atomizer 50 L/h, and source voltage + 2.9 kV. Full scan mode from m/z100–500 was done with source temperature 41°C. UPLC column used was Acquity UPLC HSS C18 1.8 μm, 2.1 × 150 mm. Solvent A was 0.1% formic acid in water, solvent B was 0.1% formic acid in acetonitrile. Solvents were set at a total flow rate of 0.4 mL/min. Isocratic elution system was run at 0–0.5 min with ratio 95:5; linear gradient of solvent A was from 95% to 5% in 15 min.

In silico analysis molecular docking and molecular dynamic

This method follow [7] with slightly modification. The three-dimensional structure of the target protein was obtained from the Protein Data Bank (PDB) in PDB format with code PDB ID 5OQV, representing Aβ42 fibril, which only one chain of 5OQV was used for docking, in this study we chose chain A beca. 5OQV had no attached or water molecules. Polar hydrogens and Kollman charges were added to the receptor and AD4 type were assigned. The receptor was then saved as PDBQT format.

Ligands identified by LC-MS (top 5 by %TIC: myricetin, gallocatechin, swietenolide, swietenine, pyrogallol) were retrieved from PubChem (SDF format), converted to 3D and protonated for pH 7.4 (OpenBabel). Gasteiger charges were assigned and ligands saved in PDBQT format.

Docking was performed using AutoDock Vina (PyRx 0.8 frontend). Blind docking has been used for this method. The grid box was centered at the coordinates (x = 38.6598, y = 60.0364, z = 53.5879) with dimensions (size x = 35.994 Å, size y = 46.7367 Å, size z = 15.5034 Å) covering all the surface of the protein. Interaction analysis was carried out using BIOVIA Discovery to identify hydrogen bonds and hydrophobic contacts, with ligands forming at least two hydrogen bonds with active site residues considered favorable. Visualization in BIOVIA Discovery Studio confirmed ligand orientation, and selection was based on energy threshold, hydrogen bonding, and site specificity to identify potential amyloidosis inhibitors.

Molecular dynamic simulation (coarse-grained)

CABS-Flex 2.0 was used with default reference settings to explore conformational variability of the docked complexes (100 cycles, generating 100 frames, roughly equivalent to 10 ns sampling). RMSF per residue was computed and compared across complexes [14]. CABS-Flex is a coarse-grained method that provides a fast approximation of backbone flexibility; it does not substitute for atomistic MD with explicit solvent. We therefore interpret RMSF results qualitatively and recommend follow-up atomistic MD (e.g., GROMACS: 100 ns) for the top compounds to quantify stability (RMSD, RMSF, Rg, H-bonds, SASA).

Results

Fermentation of Swietenia macrophylla seeds by Aspergillus niger markedly increased the levels of secondary metabolites (Table 1). Total flavonoid content in F-28 (0.115 QE/g) increased by approximately 130% compared to NF (0.05 QE/g), while total phenolic content showed a smaller increase of 4% (4.8 vs. 4.6 GAE/g). The most pronounced change was observed in total triterpenoid levels, which rose by 179% from 69.7 to 194.5 UAE/g. This trend aligns with previous studies reporting that fungal fermentation enhances the metabolite such as flavonoid and phenolic content [11]. Among the three metabolite groups, triterpenoids were the most abundant in both extracts.

Table 1.

Total flavonoids, total phenolics, and total triterpenoids content NF and F-48.

| Sample | Total flavonoids (QE/g sample) | Total phenolic (GAE/g sample) | Total triterpenoids (UAE/g sample) |

|---|---|---|---|

| NF | 0.05 ± 0.0061 | 4.6 ± 0.010536 | 69.7 ± 0.016523 |

| F-48 | 0.115 ± 0.0056 | 4.8 ± 0.0065 | 194.5 ± 0.073323 |

Based on Table 1, the observed increases after fermentation can be attributed to the enzymatic activity of Aspergillus niger. This fungus produces lignolytic enzymes capable of breaking down cell walls, releasing bound phenolics into free phenolic forms. It also produces β-glucosidase, which hydrolyzes glycosides into aglycones, facilitating the biotransformation of flavones into aglycones. A similar mechanism likely explains the increase in triterpenoids, where β-glucosidase converts glycosylated saponins into aglycones. These processes collectively enhance the availability and concentration of bioactive compounds in the fermented extract. Given these findings, the fermented extract (F-48) will be further analyzed to profile its bioactive compounds in detail and to evaluate its anti-amyloidosis in vitro and in silico.

In vitro anti amyloidosis

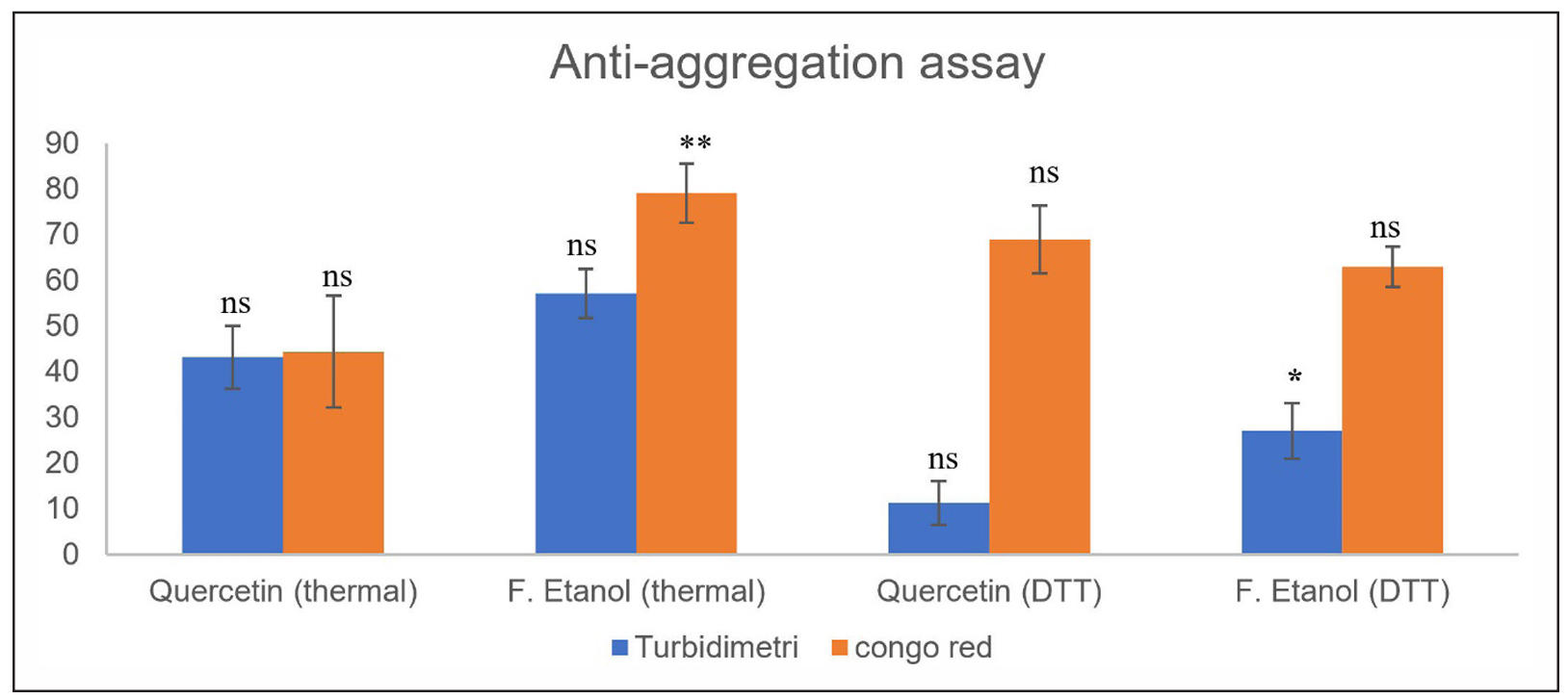

Anti-aggregation effect of the ethanol extract of Swietenia macrophylla seeds fermentation, two complementary assays were used: turbidimetric assay, which measures light scattering due to aggregate formation, and Congo red binding assay, which specifically detects amyloid fibril structures through dye interaction. The assays were performed under two stress conditions: thermal-induced denaturation and DTT-induced disulfide bond disruption. Quercetin (100 ppm) was used as a positive control. The in vitro analysis of amyloidosis shows at Figure 1.

Figure 1. In vitro analysis of amyloidosis inhibition from ethanol fraction of fermented Swietenia macrophylla seeds. Different letters/symbols indicate significant differences between treatments within the same stress group (thermal or DTT), based on one-way ANOVA and Tukey’s HSD test. P < 0.01 was considered highly significant (**), P < 0.05 was considered significant (*), while ns indicates no significant difference. Comparisons were not made between thermal and DTT groups.

Based on Figure 1, under thermal-induced stress, the ethanol fraction of fermented Swietenia mahagoni seeds (EFFSM) exhibited consistently stronger inhibitory activity than quercetin in both analytical assays. In the turbidimetric assay, EFFSM inhibited protein aggregation by 57.12 ± 5.37%, compared to 43.24 ± 6.84% for quercetin.

Similarly, in the Congo red assay, inhibition reached 79.09 ± 6.47% for the ethanol fraction, which was significantly higher (P < 0.01) than the 44.44 ± 12.23% observed for quercetin. Post-hoc Tukey HSD analysis confirmed the significance of this difference, highlighting that the ethanol fraction outperformed the positive control specifically in the Congo red assay. Interestingly, inhibition values obtained from Congo red binding were consistently higher than those from turbidimetric analysis, suggesting that Congo red is more sensitive in detecting early fibrillar intermediates or β-sheet structured aggregates that remain invisible to turbidity measurements. This observation underscores the importance of employing complementary methods to fully capture the complexity of protein aggregation processes.

In the DTT-induced aggregation model, both quercetin and EFFSM displayed reduced inhibitory effects, reflecting the more challenging conditions imposed by reductive stress. The disruption of disulfide bonds by DTT facilitates protein unfolding and exposes hydrophobic residues, promoting aggregation that is more resistant to inhibition. Under these conditions, quercetin inhibited aggregation by only 11.33 ± 4.85% in the turbidimetric assay, while the ethanol fraction achieved a significantly higher inhibition of 27.15 ± 6.09% (P < 0.01). By contrast, Congo red assay results remained relatively high for both treatments, with 69.09 ± 7.43% inhibition for quercetin and 63.00 ± 4.39% for the ethanol fraction, with no significant difference between them. This indicates that while the ethanol fraction was more effective at reducing amorphous aggregate formation (turbidity), its capacity to prevent β-sheet fibrillation under reductive stress was comparable to quercetin.

These findings indicate that the ethanol fraction is more effective against aggregation driven by thermal denaturation than by reductive stress, likely due to differences in aggregation mechanisms. Whereas thermal denaturation mainly involves hydrophobic interactions, DTT-induced aggregation is driven by disulfide bond reduction and subsequent misfolding. Given these promising results, further investigations will be performed to identify the specific bioactive compounds using LC-MS and to elucidate their molecular interactions with target proteins through in silico analysis.

Profiling metabolite Swietenia macrophylla seed fer-mented

Based on Table 2, pyrogallol acid was detected at a retention time of 0.47 minutes with 6.1% area. This simple phenolic compound is well known for its antioxidant capacity, and together with gallocatechin (4.99 min, 12.09%), a flavonoid recognized for its anti-amyloidogenic activity, may interact with protein surfaces via hydrogen bonding and aromatic stacking, thereby preventing early protein misfolding events. At 8.28 minutes, myricetin (13.89%) was identified [19]. Previous study posses that myricetin have anti-amyloidogenic activity against superoxide dismutase 1 aggregation [20].

Table 2.

Metabolites profile observed Swietenia macrophylla seed fermented extract ethanol from LCMS analysis.

| Retention time (minutes) | m/z experimental | m/z theory | Percentage area TIC (%) | Molecular formula | Compound |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0.47 | 127 | 127 | 6.1 | C6H6O3 | Pirogallic acid |

| 4.99 | 306 | 307 | 12.09 | C15H14O7 | Gallocateckin |

| 8.28 | 318 | 319 | 13.89 | C15H10O8 | Myrisetin |

| 9.01 | 509 | 509 | 17.68 | C27H34O8 | Swietenolide |

| 16.23 | 591 | 591 | 25.33 | C32H40O9 | Swietenine |

The dominant percentage area TIC was observed at 16.23 minutes, corresponding to swietenine (25.33%), another limonoid specific to mahogany along with swietenolide (17.68%), a characteristic limonoid of mahogany seeds known for its antibacterial and anti-inflammatory activities [8].

These LC-MS findings provide the basis for further in silico analysis to evaluate whether compounds with higher percentage areas also demonstrate stronger interactions with amyloidogenic targets. By correlating relative abundance with binding affinity and interaction profiles, the computational approach will help to clarify whether the predominant metabolites, particularly limonoids such as swietenine and swietenolide, play a central role in modulating protein aggregation, or whether less abundant phenolics and flavonoids contribute disproportionately through more favorable molecular interactions.

In silico: molecular docking analysis

Previous study has predicted the potential of triterpenoid compounds such as swietenine [14], swietenolide, and khayasin T to interact with Bovine Serum Albumin (BSA) through in silico docking, aiming to identify possible binding sites. Following LC-MS analysis, several new compounds were identified, namely myricetin, gallocatechin, and pyrogallol acid. However, BSA-based aggregation has limitations when used as a model of amyloid fibrillogenesis: in many experimental conditions BSA predominantly reports amorphous or non-fibrillar aggregation rather than the ordered β-sheet fibrils typical of pathogenic amyloids [14]. To strengthen interpretations of Congo red binding results and to elucidate the molecular mechanisms and candidate inhibitory compounds, we therefore complemented BSA experiments with in silico studies using β-amyloid fibril models thereby expanding the understanding of bioactive components in the sample and their possible interaction mechanisms with the target protein. Latrepiridine used for control positive through their anti-amyloidosis activity [21].

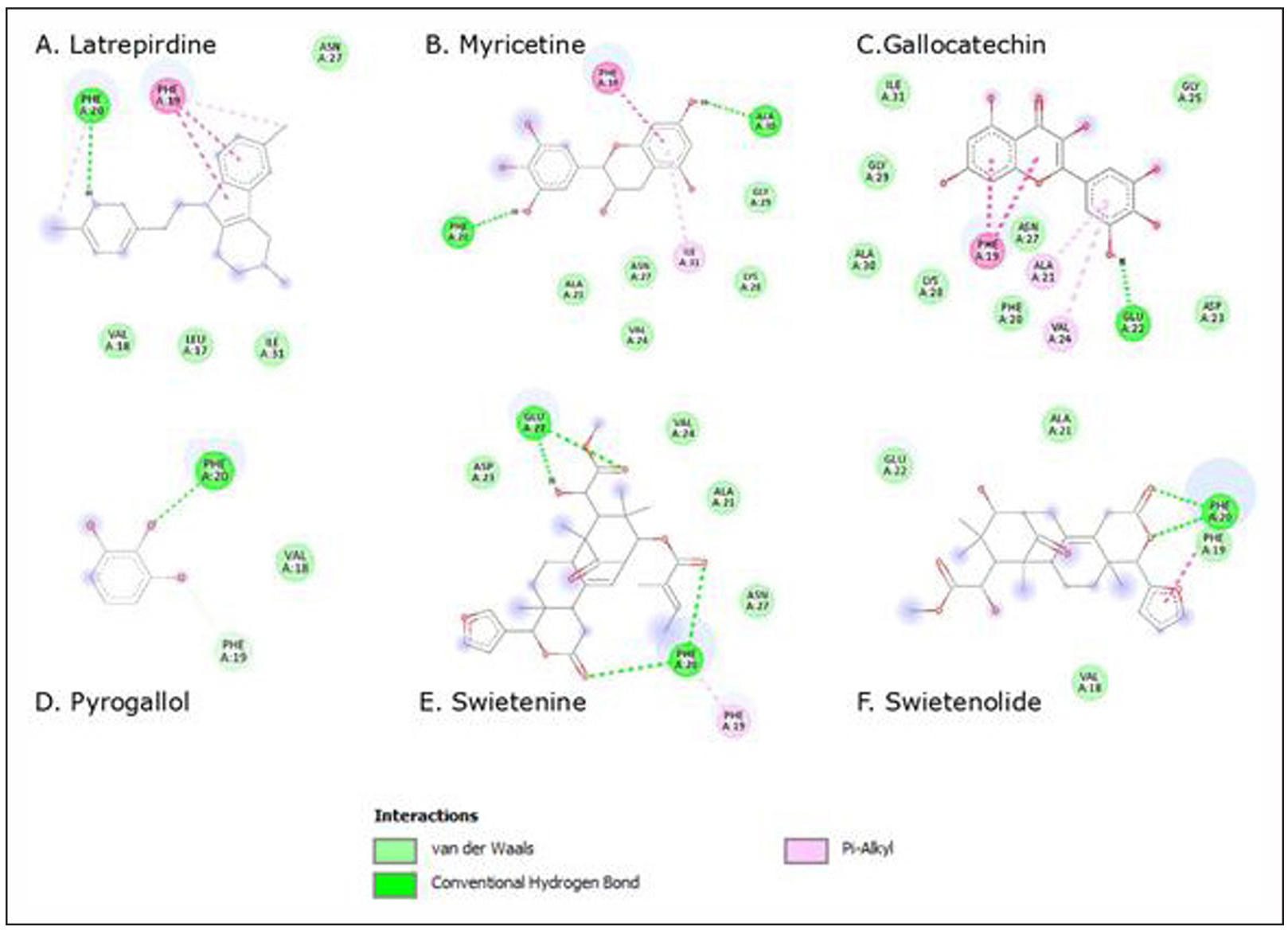

As shown as Figure 2, molecular docking was performed to evaluate the interaction between selected compounds from mahogany seed extract and β-amyloid. The binding affinities, hydrogen bonds, hydrophobic contacts, and van der Waals interactions of each ligand are summarized in Table 3 and Supplementary Table 1. Latrepirdine, used as a positive control, exhibited the strongest binding affinity (−7.2 kcal/mol), and thus served as the reference drug throughout the analysis. (−7.2 kcal/mol). Its stability was supported by a hydrogen bond with PHE19, hydrophobic interaction with PHE20, and van der Waals contacts with LEU17, VAL18, ASN27, and ILE31.

Figure 2. Interaction Aβ42 fibril with Ligands. (A) latrepirdine; (B) Myricetin; (C) Gallocatechin; (D) Pyrogallol; (E) Swietenine; (F) Swietenolide.

Table 3.

Molecular docking EFFSM compound against Aβ42 fibril.

| No | Molecule | Molecular formula | Binding affinity (kcal/mol) | Hydrogen interaction | Hydrophobic interaction | Van der walls interaction |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Latrepirdine | C21H25N3 | (-7.2) | PHE 19 | PHE 20 | LEU 17, VAL 18, ASN 27, ILE 31 |

| 2 | Pyrogallol acid | C6H6O3 | (-3.9) | PHE 20 | VAL 18, PHE 19 | |

| 3 | Gallocatechin | C15H14O7 | (-6.1) | GLU 22 | PHE 19, ALA 21,VAL 24 | ILE 33, GLY 29, ALA 30, LYS 28, PHE 20, ASP 23, GLY 25 |

| 4 | Myricetin | C15H10O8 | (-6.2) | PHE 20, ALA 30 | PHE 19, ILE 31 | ALA 21, ASN 22, VAL 24, LYS 28, GLY 29. |

| 5 | Swietenolide | C27H20O8 | (-5.8) | PHE 20 | ALA 21, GLU 22, VAL 18 | |

| 6 | Swietenine | C32H40O9 | (-5.5) | GLU 22, PHE 20 | ASP 23, VAL 24, ALA 21, ASN 27 |

Compared to latrepirdine, gallocatechin (−6.1 kcal/mol) and myricetin (−6.2 kcal/mol) relatively high affinities, suggesting comparable binding potential though still weaker than the reference. Gallocatechin formed one hydrogen bond with GLU22 and several hydrophobic interactions (PHE19, ALA21, VAL24), while myricetin established two hydrogen bonds (PHE20, ALA30) and hydrophobic contacts with PHE19 and ILE31.

Swietenolide (−5.8 kcal/mol) and swietenine (−5.5 kcal/ mol) showed moderate binding affinities. Both compounds weaker than latrepirdine, interacted mainly through hydrogen bonding at PHE20 or GLU22, supported by van der Waals contacts with residues such as ALA21, VAL18, and ASP23. Pyrogallol acid exhibited the weakest binding affinity (−3.4 kcal/mol), forming only a single hydrogen bond with PHE20 and limited van der Waals interactions. Overall, gallocatechin and myricetin were identified as the most promising test compounds, as their affinities approached that of the reference drug latrepirdine. This benchmark comparison strengthens the interpretation of their potential role as inhibitors of amyloid aggregation. To further validate these findings, Root Mean Square Fluctuation (RMSF) analysis was performed to evaluate the dynamic stability of β-amyloid residues upon ligand binding.

In silico: molecular dynamic RMSF

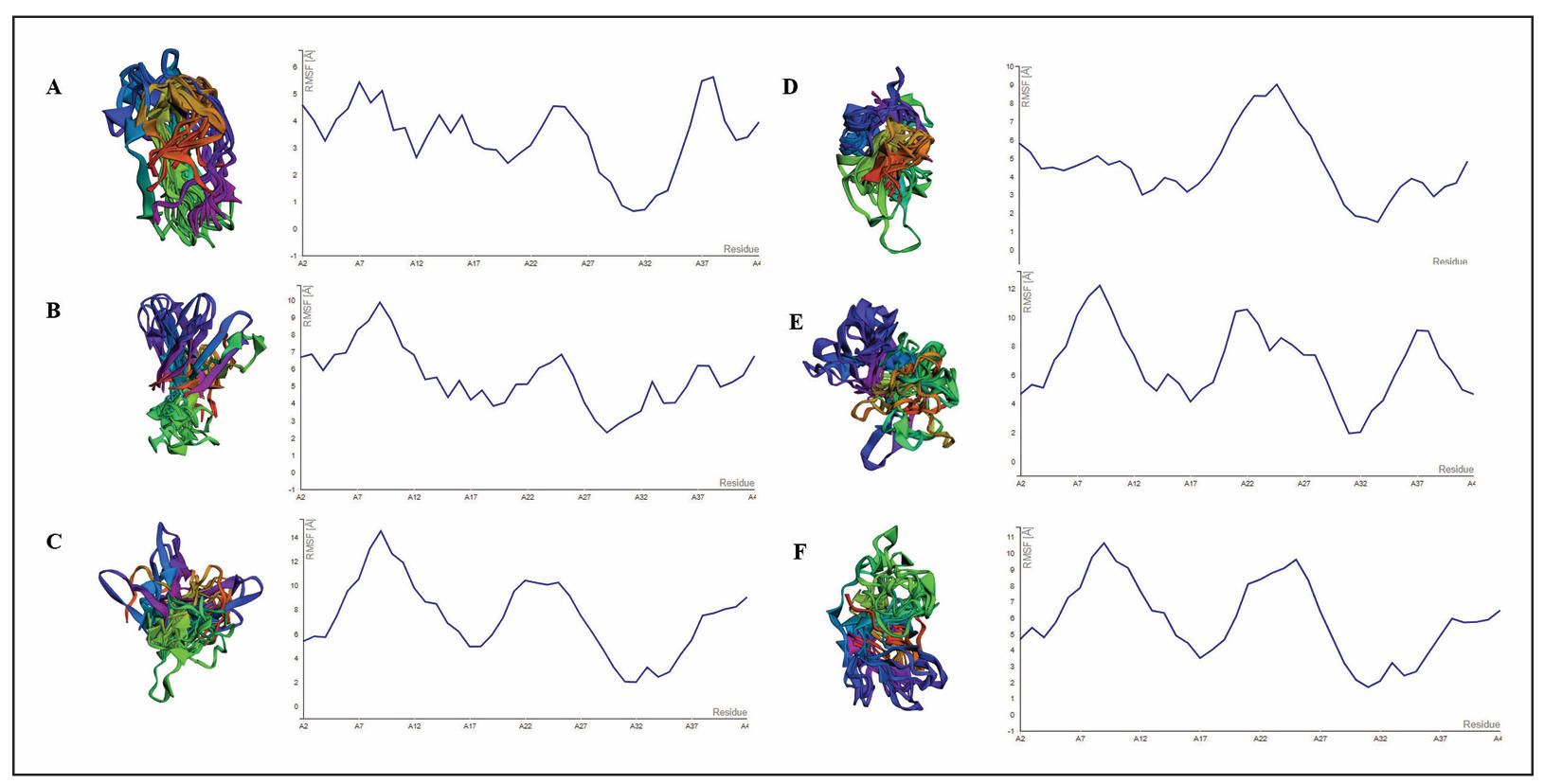

The Root Mean Square Fluctuation (RMSF) analysis was performed to evaluate the residue-level flexibility of β-amyloid in complex with each ligand, using the interaction sites of latrepirdine (Leu17, Val18, Phe19, Phe20, Asn27, and Ile31) as reference position (Supplementary Table 2).

As visualized in Figure 3 and summarized in Table 4, Latrepirdine, the positive control and reference drug, showed consistently low RMSF values across all residues, particularly at Ile31 (0.654 Å), indicating a highly stable interaction and minimal structural fluctuation of the β-amyloid backbone. This profile serves as a stability benchmark for the tested compounds.

Figure 3. Visualization of molecular dynamic simulation β-amyloid with ligands using Cabs Flex 2.0. (A) Latrepirdine, (B) Myricetin, (C) Pyrogallol, (D) Gallocatechin, (E) Swietenine, (F) Swietenolide.

Table 4.

RMSF profiles of β-amyloid binding site residues in the presence of ligands.

| Ligands | Root mean square fluctuation (Å) | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Leu17 | Val18 | Phe19 | Phe20 | Asn27 | Ile31 | |

| Latrepirdine | 3.177 | 2.961 | 2.922 | 2.430 | 3.452 | 0.654 |

| Pyrogallol | 4.964 | 4.970 | 5.917 | 7.338 | 7.545 | 2.066 |

| Gallocatechin | 3.171 | 3.598 | 4.276 | 5.280 | 6.937 | 2.459 |

| Myricetin | 4.211 | 4.770 | 3.856 | 4.058 | 4.068 | 3.201 |

| Swietenine | 4.156 | 5.021 | 5.501 | 7.667 | 7.408 | 1.952 |

| Swietenolide | 3.518 | 4.027 | 4.636 | 6.083 | 6.432 | 1.719 |

Compared with latrepirdine, gallocatechin displayed a relatively stable profile with low RMSF values at Leu17 (3.171 Å) and Val18 (3.598 Å), although higher fluctuations were observed at Asn27 (6.937 Å). Myricetin also showed moderate stability, with RMSF values ranging from 3.856–4.770 Å across residues and lower fluctua-tions at Ile31 (3.201 Å) compared to gallocatechin.

Swietenolide exhibited moderate fluctuations (3.518– 6.432 Å), while swietenine showed higher instability at Phe20 (7.667 Å) and Asn27 (7.408 Å), suggesting weaker stabilization of the amyloid residues. Pyrogallol acid demonstrated the highest RMSF across almost all residues (up to 7.545 Å at Asn27), consistent with its weak binding affinity in docking results.

Overall, RMSF analysis confirmed that gallocatechin and myricetin provide more stable interactions at the key binding residues compared to other test compounds. These results complement the docking findings, strengthening the evidence that both compounds may effectively stabilize β-amyloid structure and interfere with fibril formation.

Discussion

This study demonstrates that fermentation of Swietenia macrophylla seeds by Aspergillus niger enhances the levels of secondary metabolites, particularly triterpenoids, flavonoids, and phenolics. These biochemical modifications were associated with stronger anti-amyloidogenic activity of the ethanol fraction, as revealed by in vitro assays. Under thermal denaturation conditions, the fermented extract exhibited higher inhibitory capacity than quercetin, particularly in the Congo red assay, which sensitively detects β-sheet-rich amyloid fibrils. Even under reductive stress induced by DTT, the extract maintained notable inhibitory effects, suggesting that fermentation could improve the bioactivity of mahogany seed constituents against protein aggregation processes.

A strength of this work lies in the complementary integration of in vitro and in silico approaches. The BSA-based model provided preliminary insights into the anti-aggregation activity of the extract but remains limited, as it predominantly reflects amorphous aggregation rather than the structured β-sheet fibrils characteristic of pathogenic amyloids. To partially address this, molecular docking and RMSF analysis were conducted against β-amyloid fibrils, indicating that gallocatechin and myricetin may be the most promising compounds. Their favorable binding affinities, multiple stabilizing interactions, and relatively low RMSF values support the possibility that they contribute to the inhibitory activity observed in the Congo red assay. This integrative strategy provides suggestive evidence linking biochemical assays with molecular mechanisms, thereby increasing the plausibility of the findings.

Comparable findings have been reported in other fermented plant systems, supporting the idea that microbial fermentation can enhance anti-amyloidogenic potential through structural modification of phenolic and flavonoid compounds. For instance, fermentation of Camellia sinensis leaves by Aspergillus niger significantly increased total flavonoid levels by approximately 54%, accompanied by enzymatic hydrolysis of ester-catechins into non-ester forms with higher bioactivity [22].

Nevertheless, some limitations should be acknowledged. The in vitro assays were restricted to BSA as a model protein, which does not fully capture the structural complexity of amyloidogenic proteins in vivo. Similarly, while docking and dynamic simulations provide valuable predictions, they cannot substitute for direct biophysical validation of ligand–amyloid interactions. Future studies should include amyloid-specific proteins such as amyloid light chain or tau, combined with advanced structural analyses (e.g., TEM, CD spectroscopy, or ThT fluorescence). Moreover, bio-guided fractionation and LC-MS/MS quantification will be required to verify the active constituents and establish correlations between metabolite abundance and inhibitory potency.

Summary, the fermentation of Swietenia macrophylla seeds appears to increase the abundance of dominant limonoids such as swietenine and swietenolide while also facilitating the release of phenolic and flavonoid compounds, including myricetin and gallocatechin. Our findings suggest a possible complementary mechanism, where flavonoids such as myricetin and gallocatechin may preferentially interact with β-amyloid fibril structures, while limonoids such as swietenine and swietenolide could contribute to early aggregation inhibition. However, these interpretations remain speculative, as our study did not include fractionation or compound-combination experiments. Such possible synergistic interactions support the rationale for fermentation as a biotechnological strategy to unlock and potentiate the anti-amyloidosis activity of plant-based compounds.

Conclusions

Fermentation of Swietenia macrophylla seeds by Aspergillus niger markedly increased the levels of secondary metabolites, with total triterpenoids rising by 179% (69.7 to 194.5 UAE/g), flavonoids by 130% (0.05 to 0.115 QE/g), and phenolics by 4% (4.6 to 4.8 GAE/g). These biochemical enhancements translated into superior anti-amyloidogenic effects: under thermal stress, EFFSM inhibited BSA aggregation by 57.12% (turbidimetry) and 79.09% (Congo red), exceeding quercetin controls (43.24% and 44.44%, respectively). Under reductive stress (DTT), inhibition remained substantial at 27.15% and 63.00%. LC-MS profiling identified myricetin (13.89%) and gallocatechin (12.09%) as key flavonoids, together with dominant limonoids swietenine (25.33%) and swietenolide (17.68%). Docking results confirmed strong interactions of myricetin (−6.2 kcal/mol) and gallocatechin (−6.1 kcal/mol) with β-amyloid fibrils through residues PHE19, PHE20, ALA21, and ILE31, comparable to the positive control latrepirdine (−7.2 kcal/mol). RMSF analysis further showed that gallocatechin and myricetin stabilized critical residues (Leu17, Val18, Phe19, Phe20, Asn27, Ile31) with lower fluctuations (3.1–4.7 Å) than swietenine and swietenolide (>6 Å). Taken together, these findings provide preliminary evidence that A. niger fermentation of mahogany seeds enhances both the abundance and bioactivity of triterpenoid and flavonoid compounds, resulting in improved in vitro anti-aggregation activity. Further studies involving neuronal models are necessary to confirm any possible neuroprotective relevance.

Declarations

Acknowledgment

We sincerely thank Universitas Diponegoro for its World-Class University Program and the Adjunct Professor Program 2025 for their valuable academic support.

Authors contribution

The author contributed solely to article.

Availability of data and materials

Not applicable.

Financial support and sponsorship

This research is supported by a grant from the DIPA FSM (grant number 1263A/UN7.5.8/PP/2022).

Conflict of interest

All authors declared that there are no conflicts of interest.

Ethical approval and consent of participate

Not applicable.

References

1. Lamptey R, Chaulagain B, Trivedi R, Gothwal A, Layek B, & Singh J. A review of the common neurodegenerative disorders: current therapeutic approaches and the potential role of nanotherapeutics. Int J Mol Sci, 2022, 23(3): 1851-1861. [Crossref]

2. Makshakova O, Bogdanova L, Faizullin D, Khaibrakhmanova D, Ziganshina S, Ermakova E, et al. The ability of some polysaccharides to disaggregate lysozyme amyloid fibrils and renature the protein. Pharmaceutics, 2023, 15(2): 624-635. [Crossref]

3. Caruana M, Camilleri A, Farrugia M, Ghio S, Jakubíčková M, Cauchi R, et al. Extract from the marine seaweed Padina pavonica protects mitochondrial biomembranes from damage by amyloidogenic peptides. Molecules, 2021, 26(5): 1444-1455. [Crossref]

4. Almeida Z, & Brito R. Structure and aggregation mechanisms in amyloids. Molecules, 2020, 25(5): 1195-1206. [Crossref]

5. Rifai A, Asy'ari M, & Aminin A. Anti-aggregation effect of Ascorbic acid and Quercetin on aggregated Bovine serum albuminv induced by Dithiothreitol: comparison of turbidity and soluble protein fraction methods. Jurnal Kimia Sains dan Aplikasi, 2020, 23(4): 129-134. [Crossref]

6. Mukhopadhyay A, Stoev I, King D, Sharma K, & Eiser E. Amyloid-like aggregation in native protein and its suppression in the bio-conjugated counterpart. Frontiers in Physics, 2022, 10: 2022. [Crossref]

7. Jafar J, Mudalige H, & O. P. Protein-ligand docking study for the identification of plant-based ligands and their binding sites against Alzheimer’s disease. J Applied Learning, 2023, 1(1): 57-72.

8. Telrandhe U, Kosalge S, Parihar S, Sharma D, & Lade S. Phytochemistry and pharmacological activities of Swietenia macrophylla King (Meliaceae). Sch Acad J Pharm, 2022, 11(1): 6-12. [Crossref]

9. Qiu Y, Yang J, Ma L, Song M, & Liu G. Limonin isolated from pomelo seed antagonizes Aβ25-35-mediated neuron injury via PI3K/AKT signaling pathway by regulating cell apoptosis. Front Nutr, 2022, 9: 879028. [Crossref]

10. Dewanjee S, Paul P, Dua T, Bhowmick S, & Saha A (2020). Chapter 38-Big leaf Mahogany seeds: Swietenia macrophylla seeds offer possible phytotherapeutic intervetion against diabetic pathophysiology. Nuts and Seeds in Health and Disease Prevention (Second Edition). V. R. Preedy and R. R. Watson, Academic Press: 543-565.

11. Feitosa P, Santos T, Gualberto N, Narain N, & de Aquino Santana L. Solid-state fermentation with Aspergillus niger for the bio-enrichment of bioactive compounds in Moringa oleifera (moringa) leaves. Biocatalysis and Agri-cultural Biotechnology, 2020, 27: 101709. [Crossref]

12. Samtiya M, Aluko R, Puniya A, & Dhewa T. Enhancing micronutrients bioavailability through fermentation of plant-based foods: a concise review. Fermentation, 2021, 7(2): 63-74. [Crossref]

13. Borah A, Selvaraj S, & Murty V. Production of gallic acid from Swietenia macrophylla using tannase from Bacillus Gottheilii M2S2 in semi-solid state fermentation. Waste and Biomass Valorization, 2023, 14(8): 2569-2587. [Crossref]

14. Al-Khairi B, Asy’ari M, & Aminin A. An investigation into the anti-aggregation potential of Swietenia macrophylla Triterpenoid on Bovine serum albumin: docking and RMSF. J of Scientific and Applied Chem, 2024, 27(12): 560-568. [Crossref]

15. Ibrahim N, Mustafa S, & Ismail A. Effect of lactic fermentation on the antioxidant capacity of Malaysian herbal teas. international food research journal, 2014, 21: 1483-1488.

16. Wei L, Zhang W, Yin L, Yan F, Xu Y, & Chen F. Extraction optimization of total triterpenoids from Jatropha curcas leaves using response surface methodology and evaluations of their antimicrobial and antioxidant capacities. Electronic Journal of Biotechnology, 2015, 18(2): 88-95. [Crossref]

17. Truong D, Nguyen D, Ta N, Bui A, Do T, & Nguyen H. Evaluation of the use of different solvents for phytochemical constituents, antioxidants, and in vitro anti-inflammatory activities of Severinia buxifolia. J Food Quality, 2019, 2019(1): 8178294. [Crossref]

18. Yang M, Dutta C, & Tiwari A. Disulfide-bond scrambling promotes amorphous aggregates in lysozyme and bovine serum albumin. J Phys Chem B, 2015, 119(10): 3969-3981. [Crossref]

19. Xu B, Mo X, Chen J, Yu H, & Liu Y. Myricetin inhibits α-synuclein amyloid aggregation by delaying the liquidto-solid phase transition. Chembiochem, 2022, 23(16): e202200216. [Crossref]

20. Sharma S, Tomar V, & Deep S. Myricetin: a potent antiamyloidogenic polyphenol against superoxide dismutase 1 aggregation. ACS Chem Neurosci, 2023, 14(13): 2461-2475. [Crossref]

21. Porter T, Bharadwaj P, Groth D, Paxman A, Laws S, Martins R, et al. The effects of latrepirdine on amyloid-β aggregation and toxicity. J Alzheimers Dis, 2016, 50(3): 895-905. [Crossref]

22. Liu Y, Zhang X, Liu X, Li R, Yang X, Liao Z, et al. Enhancing the anti-aging potential of green tea extracts through liquid-state fermentation with Aspergillus niger RAF106. Foods, 2025, 14(20): 3548-3559. [Crossref]

SUPPLEMENTARY

Table S1.

Binding affinity data of ligands against β-amyloi d (Autodock Vina Result).

| Ligand | Binding Affinity | rmsd/ub | rmsd/lb |

|---|---|---|---|

| a.Binding afinity data Latrepirdine | |||

| beta_amyloid_chain_A_197033_uff_E=519.99 | -7.2 | 0 | 0 |

| beta_amyloid_chain_A_197033_uff_E=519.99 | -7 | 10.716 | 8.391 |

| beta_amyloid_chain_A_197033_uff_E=519.99 | -6.9 | 9.264 | 6.273 |

| beta_amyloid_chain_A_197033_uff_E=519.99 | -6.9 | 8.506 | 3.247 |

| beta_amyloid_chain_A_197033_uff_E=519.99 | -6.8 | 5.625 | 2.975 |

| beta_amyloid_chain_A_197033_uff_E=519.99 | -6.7 | 5.49 | 2.58 |

| beta_amyloid_chain_A_197033_uff_E=519.99 | -6.7 | 8.739 | 3.755 |

| beta_amyloid_chain_A_197033_uff_E=519.99 | -6.6 | 5.82 | 3.649 |

| beta_amyloid_chain_A_197033_uff_E=519.99 | -6.5 | 7.802 | 3.751 |

| b.Binding afinity pyrogallol acid | |||

| beta_amyloid_chain_A_1057_uff_E=62.72 | -3.9 | 0 | 0 |

| beta_amyloid_chain_A_1057_uff_E=62.72 | -3.9 | 2.778 | 0.01 |

| beta_amyloid_chain_A_1057_uff_E=62.72 | -3.7 | 8.008 | 6.542 |

| beta_amyloid_chain_A_1057_uff_E=62.72 | -3.6 | 7.624 | 6.367 |

| beta_amyloid_chain_A_1057_uff_E=62.72 | -3.6 | 10.048 | 8.702 |

| beta_amyloid_chain_A_1057_uff_E=62.72 | -3.5 | 7.476 | 6.017 |

| beta_amyloid_chain_A_1057_uff_E=62.72 | -3.5 | 4.432 | 2.49 |

| beta_amyloid_chain_A_1057_uff_E=62.72 | -3.4 | 9.655 | 8.251 |

| beta_amyloid_chain_A_1057_uff_E=62.72 | -3.4 | 29.837 | 28.676 |

| c.Binding afinity gallocathecin | |||

| beta_amyloid_chain_A_5281672_uff_E=388.01 | -6.1 | 0 | 0 |

| beta_amyloid_chain_A_5281672_uff_E=388.01 | -6.1 | 8.124 | 3.688 |

| beta_amyloid_chain_A_5281672_uff_E=388.01 | -6 | 3.439 | 1.842 |

| beta_amyloid_chain_A_5281672_uff_E=388.01 | -6 | 4.785 | 2.749 |

| beta_amyloid_chain_A_5281672_uff_E=388.01 | -5.8 | 7.054 | 1.42 |

| beta_amyloid_chain_A_5281672_uff_E=388.01 | -5.6 | 6.082 | 3.497 |

| beta_amyloid_chain_A_5281672_uff_E=388.01 | -5.6 | 7.422 | 2.336 |

| beta_amyloid_chain_A_5281672_uff_E=388.01 | -5.5 | 4.131 | 3.623 |

| beta_amyloid_chain_A_5281672_uff_E=388.01 | -5.4 | 9.126 | 7.458 |

| d. Binding afinity myricetin | |||

| beta_amyloid_chain_A_65084_uff_E=211.33 | -6.2 | 0 | 0 |

| beta_amyloid_chain_A_65084_uff_E=211.33 | -6 | 2.884 | 1.85 |

| beta_amyloid_chain_A_65084_uff_E=211.33 | -6 | 2.702 | 1.845 |

| beta_amyloid_chain_A_65084_uff_E=211.33 | -5.8 | 3.734 | 2.384 |

| beta_amyloid_chain_A_65084_uff_E=211.33 | -5.7 | 7.247 | 3.269 |

| beta_amyloid_chain_A_65084_uff_E=211.33 | -5.5 | 2.945 | 1.705 |

| beta_amyloid_chain_A_65084_uff_E=211.33 | -5.4 | 3.597 | 2.271 |

| beta_amyloid_chain_A_65084_uff_E=211.33 | -5.4 | 6.959 | 1.825 |

| beta_amyloid_chain_A_65084_uff_E=211.33 | -5.3 | 5.922 | 3.154 |

| e.Binding afinity Swietenolide | |||

| beta_amyloid_chain_A_44575315_uff_E=933.47 | -5.8 | 0 | 0 |

| beta_amyloid_chain_A_44575315_uff_E=933.47 | -5.8 | 11.187 | 7.172 |

| beta_amyloid_chain_A_44575315_uff_E=933.47 | -5.8 | 11.271 | 8.144 |

| beta_amyloid_chain_A_44575315_uff_E=933.47 | -5.6 | 8.883 | 5.028 |

| beta_amyloid_chain_A_44575315_uff_E=933.47 | -5.6 | 5.209 | 2.339 |

| beta_amyloid_chain_A_44575315_uff_E=933.47 | -5.4 | 8.959 | 4.254 |

| beta_amyloid_chain_A_44575315_uff_E=933.47 | -5.4 | 9.675 | 5.24 |

| beta_amyloid_chain_A_44575315_uff_E=933.47 | -5.3 | 4.106 | 1.908 |

| beta_amyloid_chain_A_44575315_uff_E=933.47 | -5.2 | 7.303 | 5.038 |

| f.Binding Afinity swietenine | |||

| beta_amyloid_chain_A_14262276_uff_E=966.72 | -5.5 | 0 | 0 |

| beta_amyloid_chain_A_14262276_uff_E=966.72 | -5.2 | 6.323 | 3.802 |

| beta_amyloid_chain_A_14262276_uff_E=966.72 | -5.1 | 9.289 | 4.234 |

| beta_amyloid_chain_A_14262276_uff_E=966.72 | -5 | 10.245 | 5.665 |

| beta_amyloid_chain_A_14262276_uff_E=966.72 | -4.8 | 9.818 | 5.664 |

| beta_amyloid_chain_A_14262276_uff_E=966.72 | -4.8 | 10.715 | 5.659 |

| beta_amyloid_chain_A_14262276_uff_E=966.72 | -4.6 | 25.097 | 19.914 |

| beta_amyloid_chain_A_14262276_uff_E=966.72 | -4.4 | 32.147 | 28.014 |

| beta_amyloid_chain_A_14262276_uff_E=966.72 | -4.4 | 32.769 | 28.673 |

Table S2.

RMSF data of ligands against β-amyloid.

| Residue | Root mean square fluctuation (A) | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Latrepirdine | Pyrogallol acid | Gallocathecin | Myricetin | Swietenine | Swietenolide | |

| 1 | 5,652 | 6.986 | 6.859 | 8.054 | 6.072 | 6.054 |

| 2 | 4,594 | 5.405 | 5.838 | 6.688 | 4.673 | 4.678 |

| 3 | 4,030 | 5.82 | 5.356 | 6.87 | 5.335 | 5.406 |

| 4 | 3,256 | 5.747 | 4.435 | 5.927 | 5.122 | 4.799 |

| 5 | 4,059 | 7.453 | 4.508 | 6.839 | 7.069 | 5.756 |

| 6 | 4,450 | 9.582 | 4.341 | 6.948 | 7.976 | 7.268 |

| 7 | 5,432 | 10.544 | 4.568 | 8.262 | 10.175 | 7.868 |

| 8 | 4,667 | 13.058 | 4.824 | 8.808 | 11.461 | 9.771 |

| 9 | 5,116 | 14.526 | 5.136 | 9.883 | 12.224 | 10.646 |

| 10 | 3,650 | 12.651 | 4.65 | 8.853 | 10.6 | 9.523 |

| 11 | 3,744 | 11.917 | 4.856 | 7.3 | 8.708 | 9.102 |

| 12 | 2,642 | 9.81 | 4.415 | 6.826 | 7.418 | 7.707 |

| 13 | 3,477 | 8.666 | 3.007 | 5.396 | 5.597 | 6.461 |

| 15 | 3,557 | 6.908 | 3.952 | 4.359 | 6.067 | 4.916 |

| 16 | 4,212 | 6.22 | 3.76 | 5.333 | 5.412 | 4.451 |

| 17 | 3,177 | 4.964 | 3.171 | 4.211 | 4.156 | 3.518 |

| 18 | 2,961 | 4.97 | 3.598 | 4.77 | 5.021 | 4.027 |

| 19 | 2,922 | 5.917 | 4.276 | 3.856 | 5.501 | 4.636 |

| 20 | 2,430 | 7.338 | 5.28 | 4.058 | 7.667 | 6.083 |

| 21 | 2,781 | 9.524 | 6.599 | 5.11 | 10.415 | 8.103 |

| 22 | 3,096 | 10.437 | 7.596 | 5.136 | 10.564 | 8.384 |

| 23 | 3,792 | 10.246 | 8.418 | 6.057 | 9.535 | 8.794 |

| 24 | 4,545 | 10.079 | 8.398 | 6.358 | 7.712 | 9.083 |

| 25 | 4,518 | 10.267 | 9.036 | 6.86 | 8.587 | 9.624 |

| 26 | 3,990 | 9.182 | 8.002 | 5.678 | 8.09 | 8.367 |

| 27 | 3,452 | 7.545 | 6.937 | 4.068 | 7.408 | 6.432 |

| 28 | 2,088 | 6.209 | 6.231 | 2.983 | 7.396 | 4.831 |

| 29 | 1,731 | 4.769 | 4.88 | 2.307 | 5.66 | 3.221 |

| 30 | 0.863 | 3.235 | 3.773 | 2.803 | 3.732 | 2.167 |

| 31 | 0.654 | 2.066 | 2.459 | 3.201 | 1.952 | 1.719 |

| 32 | 0.712 | 2.017 | 1.863 | 3.564 | 2.035 | 2.095 |

| 33 | 1,223 | 3.254 | 1.744 | 5.273 | 3.518 | 3.227 |

| 34 | 1,417 | 2.451 | 1.517 | 4.024 | 4.242 | 2.434 |

| 35 | 2,598 | 2.865 | 2.553 | 4.047 | 5.934 | 2.684 |

| 36 | 3,856 | 4.288 | 3.431 | 4.959 | 7.407 | 3.804 |

| 37 | 5,475 | 5.486 | 3.897 | 6.21 | 9.118 | 4.891 |

| 38 | 5,623 | 7.534 | 3.666 | 6.183 | 9.06 | 5.969 |

| 39 | 3,995 | 7.732 | 2.917 | 4.966 | 7.196 | 5.726 |

| 40 | 3,283 | 8.06 | 3.461 | 5.23 | 6.32 | 5.753 |

| 41 | 3,397 | 8.254 | 3.656 | 5.636 | 4.979 | 5.894 |

| 42 | 3,950 | 9.055 | 4.843 | 6.768 | 4.676 | 6.476 |