Open Access | Commentary

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-ShareAlike 4.0 International License.

The naturally occurring peptide GHK reverses age-related fibrosis by modulating myofibroblast function

* Corresponding author: Warren Ladiges

Mailing address: Department of Comparative Medicine, School of Medicine, University of Washington, Seattle, WA 98195, USA.

Email: wladiges@uw.edu

Received: 03 November 2024 / Revised: 04 December 2024 / Accepted: 05 December 2024 / Published: 28 December 2024

DOI: 10.31491/APT.2024.12.158

Abstract

Fibrotic disorders, such as idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis, are characterized by the accumulation of myofibroblasts, cells responsible for excessive extracellular matrix deposition and tissue remodeling. The inability to terminate this reparative process leads to persistent fibrosis with increasing age. GHK (glycyl-L-histidyl-Llysine), a naturally occurring peptide, has demonstrated the potential in modulating fibrotic pathways by reversing cellular senescence and inducing apoptosis in myofibroblasts. GHK promotes tissue regeneration and enhances wound healing by activating stemness markers like p63 and PCNA. In aging, GHK's effect on pulmonary fibroblasts may restore youthful phenotypes, improving fibroblast migration and collagen contraction. This commentary discusses the role of GHK in resolving persistent fibrosis and the molecular mechanisms underpinning these effects, including integrin-β1 signaling. The potential of GHK as a therapeutic agent for fibrosis, including combination strategies with antioxidants or anti-inflammatory agents, is also explored.

Keywords

GHK peptide, fibroblasts, myofibroblasts, senescence, fibrosis, idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis

The loss of cellular homeostasis in fibrosis is characterized by the accumulation of activated fibroblasts, known as

myofibroblasts [1], which are responsible for excessive extracellular

matrix deposition and tissue remodeling. The inability to terminate this reparative process leads to persistent

fibrosis with increasing age. Idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis (IPF) is a progressive and fatal interstitial lung

disease affecting the elderly, reflecting the significant burden it places on the aging population

[2]. Despite advances in the understanding of its clinical features, effective

treatments remain elusive, necessitating further exploration of the underlying mechanisms and novel therapeutic targets.

The myofibroblast is a key effector cell in fibrotic disorders [3],

driving extracellular matrix synthesis and tissue remodeling in progressive fibrosis [4].

Persistent activation and accumulation of myofibroblasts without resolution of the reparative response underlies

the progressive nature of fibrotic reactions in injured tissue [5].

Autopsy studies of elderly patients with IPF have highlighted the severity and irreversibility of fibrotic remodeling

in aged tissues, underscoring the importance of targeted therapeutic interventions [6].

Emerging evidence suggests that targeting senescence and associated pathways could offer novel therapeutic

strategies for IPF. GHK (glycyl-L-histidyl-L-lysine) peptide has been shown to positively influence gene expression by

regulating various cellular pathways associated with tissue repair, wound healing, and anti-aging mechanisms

[7], and thus has potential as an anti-fibrotic agent. This peptide is

naturally present in human plasma and is FDA approved for use in anti-aging skin creams. Its discovery originated

from studies comparing human plasma from young and older adults, with the younger plasma being more effective in

inducing macromolecular synthesis in rat hepatocytes and hepatoma cells [8,

9]. The active factor was found to be GHK, with human plasma levels

around 200 ng/mL at 20 years of age, declining to less than 60 ng/mL at 60 years of age. Similar observations have

been reported in animal models, including mice. Numerous studies have demonstrated that GHK accelerates wound

healing and tissue regeneration, increases collagen contraction, and triggers the secretion of factors that

promote mesenchymal cell activation [10-13].

It has been identified as a promising therapeutic candidate for fibrotic disorders due to its ability to decrease

senescence and reverse apoptosis resistance in myofibroblasts [14,

15].

Choi et al. [12] reported that GHK increased the expression

of p63 and PCNA, markers of stemness and cellular proliferation, in a keratinocyte model. p63 is a stem cell marker

that belongs to a family that includes two structurally related proteins, p53 and p73

[16], while PCNA, which is present in proliferating cells throughout the cell cycle, is a

well-established marker of proliferating cells [17]. These findings

suggest that GHK may enhance the regenerative potential of various cell types by increasing their proliferative

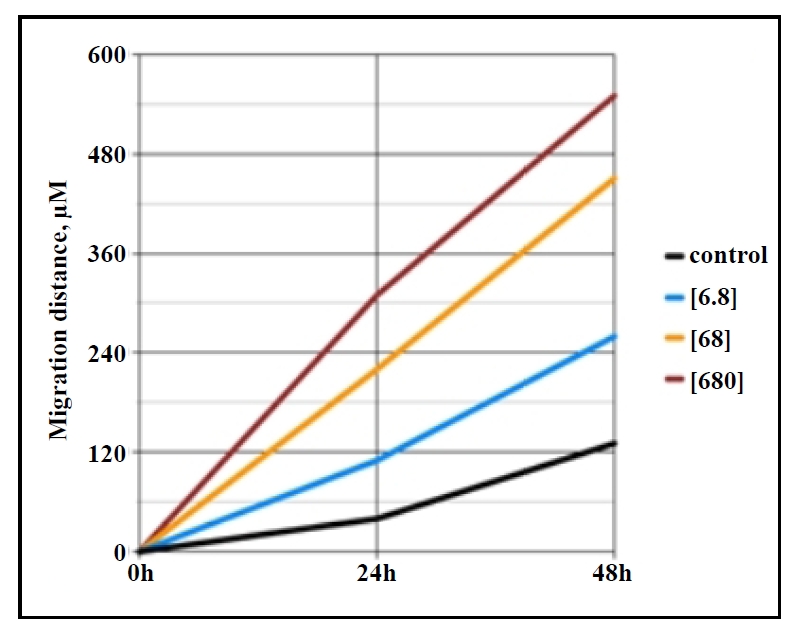

capacity. Our own research has shown that GHK promotes the migration of lung fibroblasts from aged mice

(24 months old) in a dose-dependent manner (Figure 1), indicating that it can

revert aged fibroblasts to a more youthful phenotype, potentially through the activation of mesenchymal

progenitor cells. Our preliminary data also suggest that GHK increases the expression of p63 and PCNA in primary lung

fibroblast cultures from aged mice.

Figure 1. Migration distance (µm) across the gap of monolayer primary lung fibroblasts (in vitro scratch assay) from aged (24 months) C57BL/6 mice shows increased migration with rising GHK concentrations (ng/ mL) over 0-48 hours.

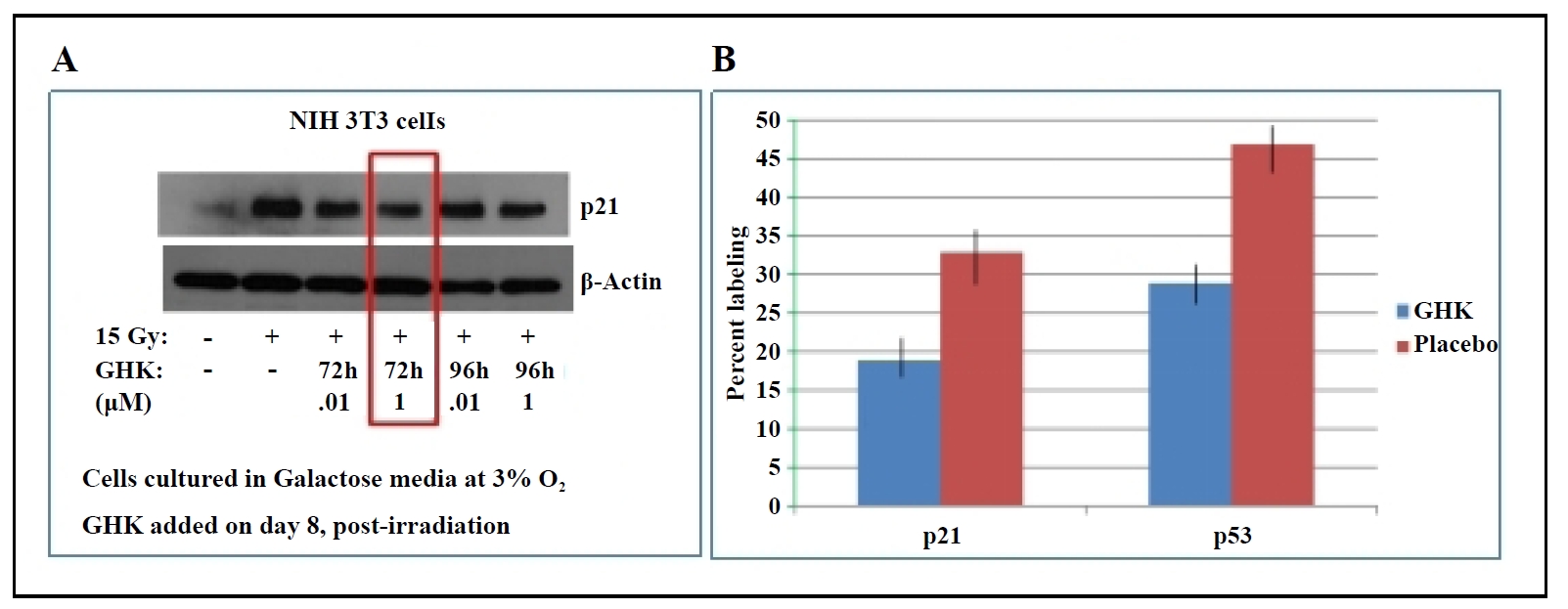

Senescent and apoptosis-resistant lung fibroblasts have been shown to contribute to the persistence and progression of fibrosis [15]. A previous study from our lab showed that primary lung fibroblasts isolated from aged mice have a senescent phenotype [18]. In irradiated 3T3 fibroblasts, GHK treatment decreased the expression of p21, a key marker of cellular senescence (Figure 2A). Similarly, in fibroblasts from 26-month-old C57BL/6 mice, GHK reduced p21 and p53 expression (Figure 2B), further supporting its role in suppressing the senescent phenotype.

Figure 2. (A) GHK decreases p21 expression in irradiated NIH 3T3 fibroblasts. (B) GHK reduces p21 and p53 expression in primary lung fibroblasts from old (26 months) C57BL/6 mice, P ≤ 0.02.

By suppressing senescence, GHK can facilitate the resolution of the persistent fibrotic process by enhancing the

apoptotic removal of excess myofibroblasts. This process could shift the fibrotic response from pathological

persistent collagen deposition to physiological collagen contraction. GHK has been shown to enhance extracellular

matrix (ECM) activity in both dermal and pulmonary fibroblasts. The molecular systems involved include actin

cytoskeletal remodeling and integrin signaling, with focal adhesion pathways facilitating attachment of fibroblasts

to collagen. Integrin beta 1 (ITGβ1), a critical cell surface protein, is actively expressed in the presence of

GHK and thus may serve as a primary target for its anti-fibrotic effect [14].

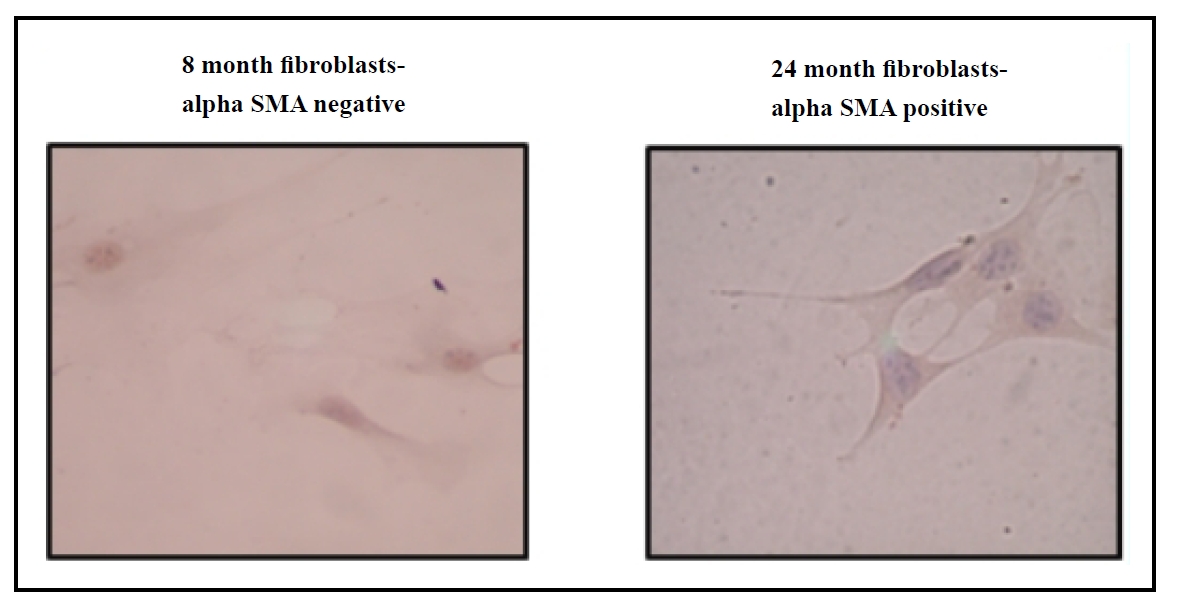

Recent evidence suggests that cellular senescence plays a role in promoting fibrosis, especially in aged tissues,

where stress-induced senescent myofibroblasts may exhibit delayed clearance with age. Our research indicates that

myofibroblast markers, such as alpha smooth muscle actin (α-SMA), are more prevalent in fibroblasts from aged mouse

lungs compared to younger controls (Figure 3), highlighting the

age-dependent increase in fibrosis susceptibility. GHK has also been shown to reverse radiation-induced senescence

in the dermis by restoring its proliferative capacity [10].

Figure 3. Increased α-SMA expression in primary lung fibroblasts from aged (24 months) C57BL/6 mice compared to young (8 months) C57BL/6 mice.

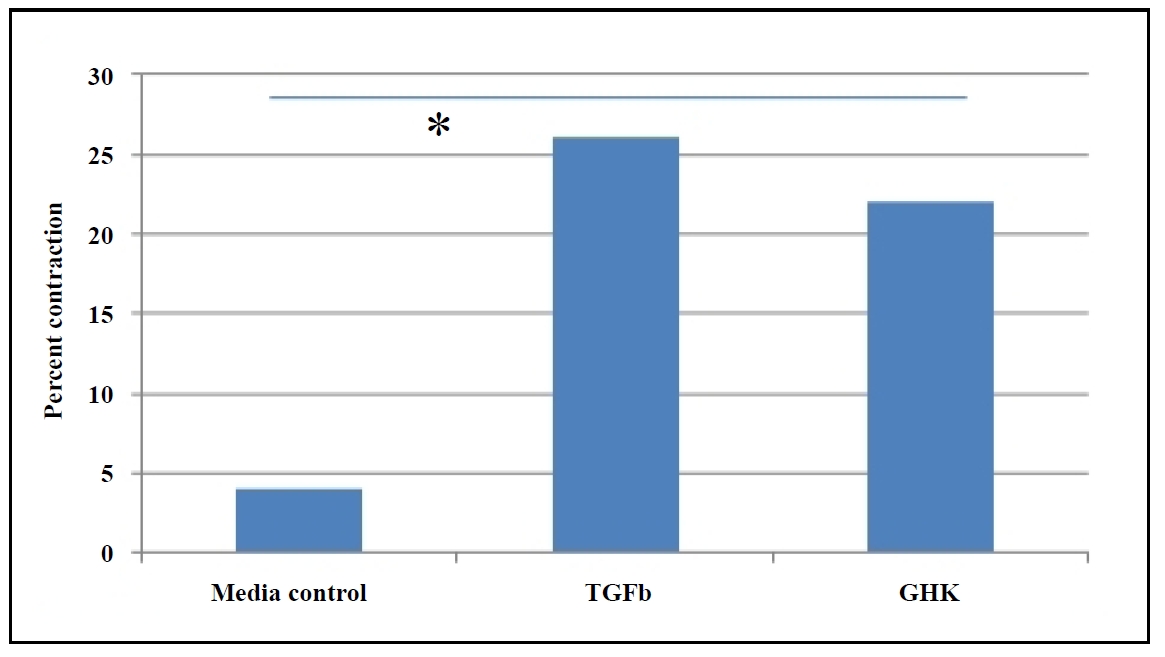

Studies have highlighted the role of persistent fibrosis in aged tissues, where myofibroblasts in injured tissues of aged mice acquire a sustained senescent and apoptosisresistant phenotype, exacerbating fibrosis (Hecker et al., 2014). GHK treatment reduces the IGF-dependent secretion of the fibrogenic growth factor (TGF-β1) [19], aiding in the resolution of persistent fibrosis and scarring. Using a collagen gel contraction assay, we observed that primary fibroblasts from the lungs of aged GHK-treated mice exhibited enhanced contraction compared to fibroblasts from placebo-treated mice (Figure 4), further supporting the hypothesis that GHK promotes the resolution of collagen scars.

Figure 4. GHK enhances collagen gel contraction in primary lung fibroblasts from aged (26 months) C57BL/6 mice, which was determined by percent contraction from initial size, P ≤ 0.05.

Cellular senescence is closely linked to fibrosis, as demonstrated by nonproliferative, p16-positive myofibroblasts in

fibrotic lung tissues [15]. Such observations have also been seen

in human liver cirrhosis [20]. Resolution of fibrosis is preceded by apoptosis

of myofibroblasts and clearance of the extracellular matrix [21].

Thus, the transition from "physiological" to "pathological" fibrosis is driven by impaired apoptosis of myofibroblasts,

as well as excessive ECM deposition and accumulation, resembling a persistent wound-healing response.

Senescent fibroblasts exhibit higher expressions of Bcl-2, conferring resistance to apoptosis

[22]. Bcl-2 overexpression has been observed in fibroblasts isolated from aged mice with

bleomycin-induced lung fibrosis [15], consistent with this mechanism.

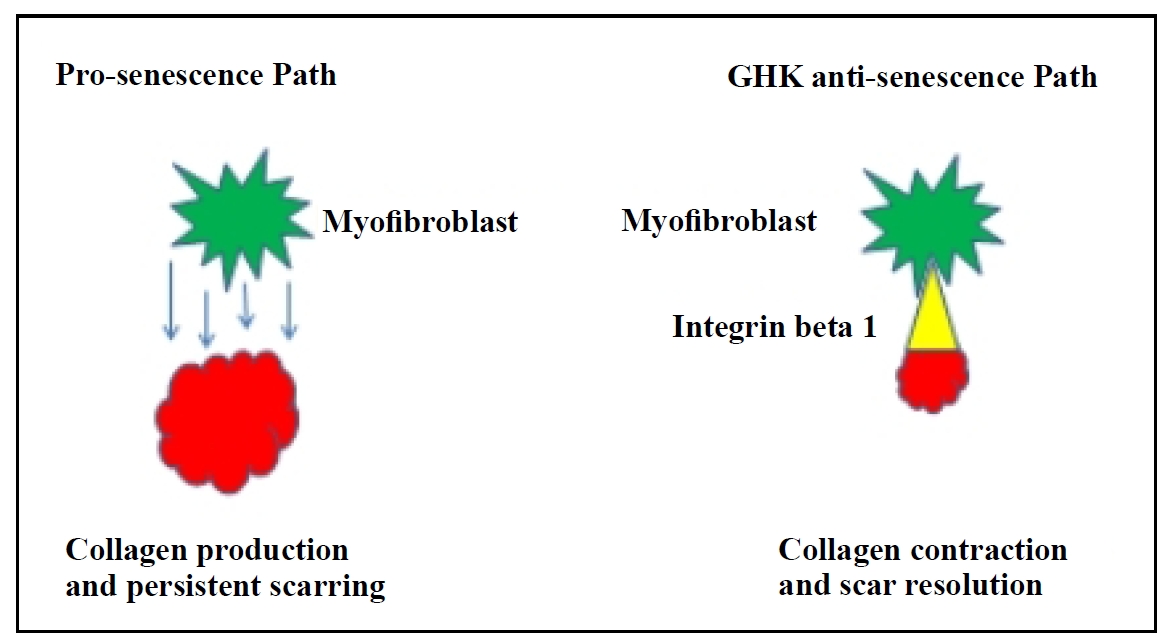

GHK appears to directly target myofibroblasts, converting pathological persistent collagen deposition to physiological

collagen contraction through ITG-β1 activation and apoptotic elimination of excess myofibroblasts

(Figure 5). In preclinical studies, complete resolution of fibrosis in preclinical

studies would be the ideal outcome, advancing GHK towards clinical trials. Should fibrosis remain

partially unresolved, alternative strategies could enhance the anti-fibrotic effects of GHK. One possibility

would be combining GHK with antioxidants, such as the mitochondrial targeted antioxidant SS31

[23], given the role of redox imbalance in persistent lung fibrosis

[15]. Another potential approach could involve combining GHK with an

anti-inflammatory agent. While GHK has been shown to inhibit the inflammatory response and epithelial-mesenchymal

transition (EMT) via the TGF-β1/Smad 2/3 and IGF-1 pathways in bleomycin-induced fibrosis models

[24], its broader anti-inflammatory effects in the context of pulmonary

fibrosis pathogenesis may warrant further exploration.

Figure 5. Proposed mechanism of GHK: reversal of senescence in lung fibroblasts and activation of integrin (ITG)-β1 to resolve persistent fibrosis.

Declarations

Availability of data and materials

Not applicable.

Financial support and sponsorship

This work was supported by NIH grant R01 AG057381, Ladiges, PI.

Conflicts of interest

Warren Ladiges is a member of the editorial board of Aging Pathobiology and Therapeutics. The authors declare that they have no conflicts and were not involved in the journal's review or decision regarding this manuscript.

Ethical approval and informed consent

Not applicable.

References

1. King TEJ, Schwarz MI, Brown K, Tooze JA, Colby TV, Waldron JA, Jr., et al. Idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis: relationship between histopathologic features and mortality. Am J Respir Crit Care Med, 2001, 164(6): 1025-1032. [Crossref]

2. Raghu G, Weycker D, Edelsberg J, Bradford WZ, & Oster G. Incidence and prevalence of idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis. Am J Respir Crit Care Med, 2006, 174(7): 810-816. [Crossref]

3. Hinz B, Phan SH, Thannickal VJ, Galli A, Bochaton-Piallat ML, & Gabbiani G. The myofibroblast: one function, multiple origins. Am J Pathol, 2007, 170(6): 1807-1816. [Crossref]

4. Duffield JS, Lupher M, Thannickal VJ, & Wynn TA. Host responses in tissue repair and fibrosis. Annu Rev Pathol, 2013, 8: 241-276. [Crossref]

5. Thannickal VJ, Toews GB, White ES, Lynch JP, 3rd, & Martinez FJ. Mechanisms of pulmonary fibrosis. Annu Rev Med, 2004, 55: 395-417. [Crossref]

6. Araki T, Katsura H, Sawabe M, & Kida K. A clinical study of idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis based on autopsy studies in elderly patients. Intern Med, 2003, 42(6): 483-489. [Crossref]

7. Pickart L, Vasquez-Soltero JM, & Margolina A. GHK and DNA: resetting the human genome to health. Biomed Res Int, 2014, 2014: 151479. [Crossref]

8. Pickart L, & Thaler MM. Tripeptide in human serum which prolongs survival of normal liver cells and stimulates growth in neoplastic liver. Nat New Biol, 1973, 243(124): 85-87.

9. Pickart L, Thayer L, & Thaler MM. A synthetic tripeptide which increases survival of normal liver cells, and stimulates growth in hepatoma cells. Biochem Biophys Res Commun, 1973, 54(2): 562-566. [Crossref]

10. Pollard JD, Quan S, Kang T, & Koch RJ. Effects of copper tripeptide on the growth and expression of growth factors by normal and irradiated fibroblasts. Arch Facial Plast Surg, 2005, 7(1): 27-31. [Crossref]

11. Pickart L. The human tri-peptide GHK and tissue remodeling. J Biomater Sci Polym Ed, 2008, 19(8): 969-988.[Crossref]

12. Choi HR, Kang YA, Ryoo SJ, Shin JW, Na JI, Huh CH, et al. Stem cell recovering effect of copper-free GHK in skin. J Pept Sci, 2012, 18(11): 685-690. [Crossref]

13. Jose S, Hughbanks ML, Binder BY, Ingavle GC, & Leach JK. Enhanced trophic factor secretion by mesenchymal stem/stromal cells with Glycine-Histidine-Lysine (GHK)-modified alginate hydrogels. Acta Biomater, 2014, 10(5): 1955-1964. [Crossref]

14. Campbell JD, McDonough JE, Zeskind JE, Hackett TL, Pechkovsky DV, Brandsma CA, t al. A gene expression signature of emphysema-related lung destruction and its reversal by the tripeptide GHK. Genome Med, 2012, 4(8): 67-77. [Crossref]

15. Hecker L, Logsdon NJ, Kurundkar D, Kurundkar A, Bernard K, Hock T, et al. Reversal of persistent fibrosis in aging by targeting Nox4-Nrf2 redox imbalance. Sci Transl Med, 2014, 6(231): 231ra247. [Crossref]

16. Pellegrini G, Dellambra E, Golisano O, Martinelli E, Fantozzi I, Bondanza S, et al. p63 identifies keratinocyte stem cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA, 2001, 98(6): 3156-3161. [Crossref]

17. Bravo R, Frank R, Blundell PA, & Macdonald-Bravo H. Cyclin/PCNA is the auxiliary protein of DNA polymerasedelta. Nature, 1987, 326(6112): 515-517. [Crossref]

18. Ge X, Pettan-Brewer C, Morton J, Carter K, Fatemi S, Rabinovitch P, et al. Mitochondrial catalase suppresses naturally occurring lung cancer in old mice. Pathobiol Aging Age Relat Dis, 2015, 5: 28776. [Crossref]

19. Gruchlik A, Chodurek E, & Dzierzewicz Z. Effect of GLYHIS-LYS and its copper complex on TGF-β secretion in normal human dermal fibroblasts. Acta Pol Pharm, 2014, 71(6): 954-958.

20. Sagiv A, Biran A, Yon M, Simon J, Lowe SW, & Krizhanovsky V. Granule exocytosis mediates immune surveillance of senescent cells. Oncogene, 2013, 32(15): 1971-1977. [Crossref]

21. Desmoulière A, Redard M, Darby I, & Gabbiani G. Apoptosis mediates the decrease in cellularity during the transition between granulation tissue and scar. Am J Pathol, 1995, 146(1): 56-66.

22. Sanders YY, Liu H, Zhang X, Hecker L, Bernard K, Desai L, et al. Histone modifications in senescence-associated resistance to apoptosis by oxidative stress. Redox Biol, 2013, 1(1): 8-16. [Crossref]

23. Szeto HH, & Birk AV. Serendipity and the discovery of novel compounds that restore mitochondrial plasticity. Clin Pharmacol Ther, 2014, 96(6): 672-683. [Crossref]

24. Zhou XM, Wang GL, Wang XB, Liu L, Zhang Q, Yin Y, et al. GHK peptide inhibits bleomycin-induced pulmonary fibrosis in mice by suppressing TGFβ1/Smad-mediated epithelial-to-mesenchymal transition. Front Pharmacol, 2017, 8: 904-915. [Crossref]