Open Access | Research Article

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-ShareAlike 4.0 International License.

Mitochondrial-targeted methionine sulfoxide reductase overexpression increases the production of oxidative stress in mitochondria from skeletal muscle

* Corresponding author: Adam B. Salmon

Mailing address: Department of Molecular Medicine, UT Health

San Antonio, San Antonio TX, USA.

E-mail: salmona@uthscsa.edu

Received: 21 February 2020 / Accepted: 13 March 2020

DOI: 10.31491/APT.2020.03.012

Abstract

Objective: Mitochondrial dysfunction comprises part of the etiology of myriad health issues, particularly those

that occur with advancing age. Methionine sulfoxide reductase A (MsrA) is a ubiquitous protein oxidation repair enzyme that specifically and catalytically reduces a specific epimer of oxidized methionine: methionine

sulfoxide. In this study, we tested the ways in which mitochondrial bioenergetic functions are affected by increasing MsrA expression in different cellular compartments.

Methods: In this study, we tested the function of isolated mitochondria, including free radical generation, ATP

production, and respiration, from the skeletal muscle of two lines of transgenic mice with increased MsrA expression: mitochondria-targeted MsrA overexpression or cytosol-targeted MsrA overexpression.

Results: Surprisingly, in the samples from mice with mitochondrial-targeted MsrA overexpression, we found

dramatically increased free radical production though no specific defect in respiration, ATP production, or

membrane potential. Among the electron transport chain complexes, we found the activity of complex I was

specifically reduced in mitochondrial MsrA transgenic mice. In mice with cytosolic-targeted MsrA overexpression, we found no significant alteration made to any of these parameters of mitochondrial energetics.

Conclusions: There is also a growing amount of evidence that MsrA is a functional requirement for sustaining optimal mitochondrial respiration and free radical generation. MsrA is also known to play a partial role in

maintaining normal protein homeostasis by specifically repairing oxidized proteins. Our studies highlight a potential novel role for MsrA in regulating the activity of mitochondrial function through its interaction with the

mitochondrial proteome.

Keywords

Superoxide, oxidative stress, mitochondria, protein homeostasis, electron transport chain

Introduction

Mitochondrial dysfunction is a causative factor of numerous diseases and pathologies and may be a potential

primary driver of the aging process itself. One cause of

mitochondrial dysfunction in vivo is the loss of mitochondrial protein homeostasis (mito-proteostasis) which is the

tightly regulated balance of protein translation, protein

quality control, and protein degradation. Mito-proteostasis

is complicated by two significant factors: First, > 90% of

the mitochondrial proteome is translated in the cytosol

and imported to the mitochondria in an unfolded state, in

which it is highly susceptible to oxidation [1]. Second,

relative to the cytosolic proteome, the mitochondrial proteome is highly enriched in methionine, which is one of

the most readily oxidized amino acids due to its side-chain

sulfur atom [2, 3]. The sequence of some of the proteins

that make up the electron transport chain complexes are compromised of 8-13% methionine of their amino acid

content in contrast to an average usage rate of 2.2-2.8%

among all cellular proteins [2]. Thus, there is a conundrum

as to why the highly oxidative environment of mitochondria would contain such a high amount of easily oxidized

proteins.

Among the eukaryotic antioxidant defenses, methionine

sulfoxide reductase A (MsrA) plays a unique role in the

oxidative repair, and potentially redox regulation, of proteins in the cells. MsrA has been classically defined as a

repair enzyme capable of the catalytic reduction of oxidized methionine or methionine sulfoxides [4]. The subsequent discovery of other methionine sulfoxide reductases

also pointed out that there is stereo-specificity among such

enzymes with MsrA capable of the reduction of primarily

the S-epimer of methionine sulfoxide. However, there is a

growing amount of evidence that MsrA plays a larger role

in the regulation of cellular homeostasis. For example,

MsrA has also been shown to have a stereo-specific oxidase activity targeted toward methionine [5]. MsrA may

then be capable of regulating protein function through.

the redox regulation of methionine residues [6]. In addition, MsrA has been shown to play a protein chaperonelike role in folding proteins; MsrA preferentially repairs

oxidized methionine in unfolded proteins and protects

these proteins from oxidative protein misfolding [7].

Lastly, MsrA may assist in targeting excessively damaged

proteins for proteasome-mediated degradation through

ubiquitin-like protein modifications that are distinct from

its catalytic modification function [8].

MsrA is expressed ubiquitously in mammals and, at the

sub-cellular level, is located natively in both the cytosol

and mitochondria. In yeast, the deletion of MsrA significantly increased the production of reactive oxygen species

(ROS) and reduced mitochondrial efficiency when yeast

are grown on substrates of the electron transport chain

(ETC) [9]. These defects were not ascribed to reduced mitochondrial number but rather a reduced number of competent mitochondria in MsrA-deleted yeast. In mammalian

retinal pigment epithelial (RPE) cells, the knockdown of

MsrA reduced mitochondrial ATP content and the activity

of ETC complex IV [10]. Conversely, the adenoviral overexpression of MsrA in RPE cells increased mitochondrial

ATP and boosted ETC complex IV activity. Mitochondria

isolated from a mouse model of Alzheimer’s disease also

lacking MsrA similarly showed reduced oxygen consumption and ETC complex IV activity [11]. Mice lacking

MsrA have also shown increased mitochondrial fragmentation and damage following exposure to the DNA

damaging agent cisplatin [12]. Collectively, these findings

suggest the role of MsrA and, indirectly, the regulation of

methionine oxidation, in preserving normal mitochondrial

energetic function.

In this study, we used two murine models showing the

increased expression of MsrA targeted primarily to either

the mitochondria or cytosol. Endogenously, the sub-cellular localization of MsrA is determined by the alternative

translation initiation sites, which include (or do not) an Nterminal mitochondrial targeting sequence on the native

translated protein. While the native distribution of MsrA

is ~3:1 cytosolic to mitochondrial, here, we used two

different transgenic MsrA mouse strains to test whether

increasing MsrA in either subcellular compartment would

alter the mitochondrial bioenergetics or function. We (and

others) have reported that TgCyto MsrA mice have increased levels of cytosolic MsrA due to a deletion of the

endogenous mitochondrial targeting sequence of MsrA in

the overexpressed transgene [13-15]. Conversely, TgMito

MsrA exhibits the preferential overexpression of mitochondrial-targeted MsrA due to its preferential expression

of the endogenous mitochondrial targeting sequence of

MsrA in the transgene [13, 14, 16]. In this study, we tested

the energetic and oxidative stress characteristics of mitochondria isolated from the skeletal muscle of these mice

to address the potential role of MsrA in murine mitochondrial function.

Materials and Methods

Animals

All studies in this research were reviewed and approved by the UT Health San Antonio (UTHSA) Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee (IACUC), which is responsible for regularly monitoring housing and animal conditions to ensure all guidelines are met for the safety and health of the animals. All experiments were conducted in compliance with the US Public Health Service’s Policy on Humane Care and Use of Laboratory Animals and the Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals. We have previously reported the generation and breeding of TgCyto MsrA and TgMito MsrA mice [13, 14, 16]. In this study, young mice (5-7 months of age) were used and fed a normal animal chow (NIA-31) diet for their life. The animals were sacrificed with CO2, and muscle and other tissues were collected.

Mitochondrial function assays

Mitochondria were isolated from freshly collected hindlimb skeletal muscle (gastrocnemius, tibialis, and soleus) using the methods previously described [17]. Briefly, the muscles were homogenized with protease, and the mitochondria were purified through differential centrifugation. H2O2 release from the mitochondria under specified conditions was assessed using the Amplex Red method as is described in [18]. Mitochondrial substrates were added at the following concentrations: glutamate (2.5 mM), malate (2.5 mM), succinate (5 mM), rotenone (0.5 µM), and antimycin A (0.5 µM). The same concentrations were used for ATP production, membrane potential, and mitochondrial respiration. Superoxide release was measured using electron paramagnetic resonance (EPR) with the use of spin trap 5-diisopropoxyphosphoryl-5-methyl-1-pyrroline-Noxide (DIPPMPO), as previously described [17]. EPR data was expressed as relative intensity per 20 µg mitochondrial protein and then normalized to values generated from the control mice. ATP synthesis was measured using the luciferin/luciferase assay from Roche according to the manufacturers’ instructions. The slope of the kinetic curve generated was converted to ATP measurements using the standards provided in the kit. Membrane potential was measured by the fluorescence of the quench-dye Safarin O, as previously described [18]. The respiratory control ratio (RCR) was measured as the ratio of the mitochondrial State 3/State 4 respiration rates measured by the Clark electrode, as described previously [17, 18]. Briefly, State 3 respiration was measured in the presence of 0.3 mM ADP, and State 4 respiration was measured as oxygen consumption following the expenditure of ADP. Aconitase catalyzes the reversible isomerization of citrate into isocitrate. In most tissues, aconitase is usually present in both the mitochondrial matrix and the cytoplasm. However, in skeletal muscle, only mitochondrial matrix aconitase is present. Aconitase activity was assayed (in Triton-X- 100-treated samples) by measuring NADP+ reduction via citrate in the presence of isocitrate dehydrogenase using a fluorometric method (excitation at 355 nm and emission at 460 nm). Skeletal muscle homogenates (~1.0 mg of protein/ml) were aliquoted in 96-well plates (100 μl of pH 7.44, 125 mm KCl, 10 mm HEPES, 5 mm MgCl2, 2 mm K2HPO4) and incubated at 30° C for up to 40 min. After incubation, aconitase activity measurements began via the addition of 1 volume (100 μl) of 50 mm Tris, 0.6 mm MnCl2, 60 mm citrate, 0.2% Triton X-100, 100 μm NADP+, and 1 unit of isocitrate dehydrogenase (Sigma). Fluorometric measurements were then initiated immediately (Fluoroskan-FL Ascent type 374 microplate reader). As a negative control, we used a blank consisting of the same buffer minus the isocitrate dehydrogenase. Assessment of the slope of NADPH fluorescence change was used for the assessment of aconitase activity.

Mitochondrial complex assays

The activity of the ETC complexes was measured as previously described [17]. In brief, total mitochondrial proteins were assessed for complex I activity by monitoring the oxidation of nicotinomide adenine dinucleotide (NADH), with ubiquinone-2 as the electron acceptor in the presence of diclorophenolindophenol (DCIP). Complex II activity was assessed by measuring the succinatedependent reduction of DCIP, using ubiquinone-2 as the electron receptor. Complex III activity was measured by the reduction of cytochrome c3+ at 550 nm, using D-ubiquinol-2 as an electron acceptor. Complex IV was measured by monitoring the oxidation of cytochrome c2+. All assays were measured via spectrophotometry, and they are described in greater detail as in [17]. The final rates for all activities were normalized to the average values obtained for the wild type (control) animals.

Statistical analysis

All data was analyzed by a one-way ANOVA or Student’s t-test, as appropriate. Statistical significance was given to data where p < 0.05. Post-hoc analysis of the ANOVA was performed using the method of Holm-Sidak.

Results

Based on reports suggesting a lack of MsrA causes mitochondrial dysfunction, we tested whether isolated mitochondria from mice with elevated MsrA levels, either primarily in the cytosol or primarily in the mitochondria, would differ from those of control mice. We first addressed the rates of H2O2 production as a marker of mitochondrial-derived reactive oxygen species (ROS) production. Under basal respiration, H2O2 production was low and did not differ among the genotypes (Figure 1A). When provided with glutamate and malate (substrates for ETC complex I), H2O2 production was significantly elevated; interestingly, under these conditions, H2O2 production was nearly four times greater in TgMito MsrA mitochondria than in the control or TgCyto MsrA mitochondria (Figure 1B), we found that mitochondria from all three genotypes showed similarly high rates of H2O2 production when glutamate, malate and rotenone, an inhibitor of ETC complex I, were added (Figure 1C). H2O2 production was still significantly elevated in TgMito MsrA compared to control and TgCyto MsrA mitochondria when succinate, a substrate of the ETC complex II, was added (Figure 1D). With the addition of antimycin A, an inhibitor of ETC complex III, we found a similar difference between TgMito MsrA and control ROS production; however, this did not reach statistical significance (Figure 1E). For all assays, we found no difference in ROS production between the mitochondria of the TgCyto MsrA and control mice.

Figure 1. Mitochondrial production of H2O2 with no substrates provided (A; state 1) or provided with glutamate and malate (B; Glu/Mal), glutamate, malate and rotenone (C; Glu/Mal/Rot), succinate and rotenone (D; Suc/Rot) or succinate, rotenone and antimycin A (E; Suc/Rot/AA). Skeletal muscle mitochondria was isolated from wild type (Control),TgMito MsrA (Mito) and TgCyto MsrA (Cyto) mice. Bars represent average values for n=5 for each group ± SEM. Asterisks indicate group differs significantly from others by ANOVA (p < 0.05).

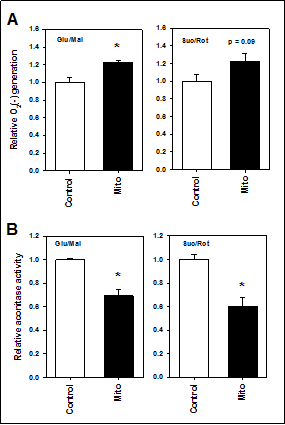

Because mitochondria do not produce H2O2 directly, we also measured superoxide production from isolated mitochondria using electron paramagnetic resonance (EPR). Whether substrates of ETC complex I (glutamate and malate) or complex II (succinate with rotenone to inhibit complex I) were provided, superoxide generation was higher in the mitochondria of TgMito MsrA mice than the control using this method (Figure 2A). We also measured whether superoxide are released into the mitochondria through a measurement of aconitase activity Aconitase activity is inhibited in the mitochondrial matrix via interaction with superoxide [19]. The significantly reduced activity of aconitase in TgMito MsrA mitochondria again suggested elevated levels of superoxide with increasedmitochondrial MsrA (Figure 2B).

Figure 2. (A) Superoxide generation from mitochondria isolated from muscle of wild type (Control) and TgMito MsrA (mito) mice provided glutamate and malate (Glu/Mal) or succinate and rotenone (Suc/Rot). (B) Aconitase activity in isolated mitochondria provided glutamate and malate (Glu/Mal) or succinate and rotenone (Suc/Rot). Bars represent average values for n=6 for each group ± SEM. Asterisks indicate significant difference as measured by t-test (p < 0.05).

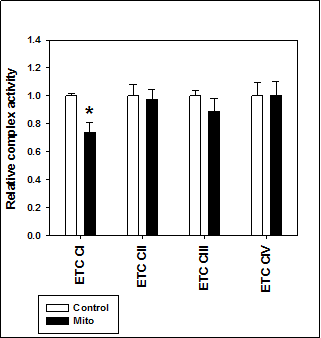

Of the potential sources of mitochondrial superoxide production, we focused on the activity of the ETC complexes, especially ETC complex I and III, as potential mechanisms for these differences. In isolated mitochondria, we found a significant reduction in ETC Complex I activity in TgMito MsrA mitochondria compared to the controls (Figure 3). ETC Complex II, III, and IV were all similar between the two genotypes, suggesting this could be the potential source of increased superoxide generation in TgMito MsrA mitochondria.

Figure 3. Electron transport chain complex activity in isolated mitochondria from wild type (Control) and TgMito MsrA mice (Mito). Bars represent average values for given complex for n=5 for each group ± SEM. Asterisks indicate significant difference as measured by t-test (p < 0.05).

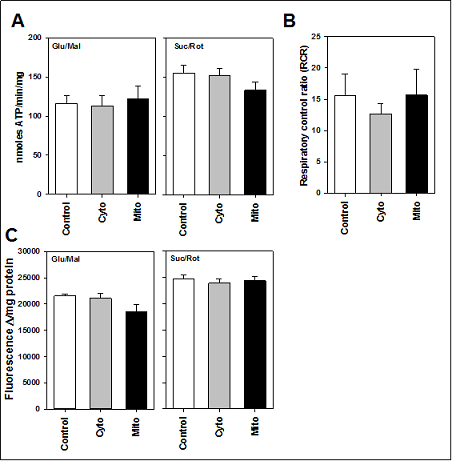

Despite the increase in free radical production and the reduction in ETC Complex I activity, we found little detrimental effect on the actual bioenergetics of mitochondria from TgMito MsrA mice. Moreover, ATP production did not differ among the three genotypes of mice when generating ATP from ETC Complex I (glutamate and malate) or complex II (succinate and rotenone to inhibit Complex I). Similarly, increasing MsrA levels had no effect on the respiratory control ratio (RCR) of mitochondria or the mitochondrial membrane potential (Figure 4).

Figure 4. (A) ATP production from isolated mitochondria provided glutamate and malate (Glu/Mal) or succinate and rotenone (Suc/Rot). (B) Respiratory control ratio (RCR) of mitochondria provided glutamate and malate. (C) Membrane potential of isolated mitochondria provided glutamate and malate (Glu/Mal) or succinate and rotenone (Suc/Rot). Skeletal muscle mitochondria was isolated from wild type (Control),TgMito MsrA (Mito) and TgCyto MsrA (Cyto) mice. Bars represent average values for n=5 for each group ± SEM. Asterisks indicate group differs significantly from others by ANOVA (p < 0.05).

Discussion

Contrary to our initial prediction, our findings suggest that

elevated levels of MsrA in the mitochondria lead to the increased generation of mitochondrial-derived free radicals

without significantly affecting mitochondrial bioenergetics. These outcomes raise interesting questions, the first of which asks why increasing mitochondrial MsrA might

reduce ETC complex I activity. Of note, mammalian complex I is highly enriched in overall methionine content

of its proteins, with up to four times the quantity of methionine compared to the methionine content of the total

cellular proteome [2]. It has been proposed that a high

methionine content might act as an antioxidant or “free

radical sink” within the highly oxidative environment of

mitochondria [2, 20]. Moreover, the majority of proteins

making up this complex are imported to the mitochondria

as unfolded proteins [21]. As MsrA has been shown to

preferentially bind unfolded proteins [7], it may be that

the overabundance of MsrA in mitochondria from TgMito

MsrA mice may be physically bound to these components,

potentially inhibiting the proper folding of the complex

structures. While the levels of MsrA expressed in these

mice may be much higher than normally expressed in

vivo [14, 16], these results raise the intriguing possibility

that MsrA plays a protein chaperone-like function in the

assembly of mitochondrial protein complexes.

We have previously shown that TgMito MsrAs are protected against glucose metabolic dysfunction caused by

either high fat diets or advanced age [14, 16]. In light of

the results presented here, these physiological outcomes

are intriguing because there has been some consensus

that oxidative stress is associated with, and may cause,

metabolic dysfunction, including insulin resistance [15,

22]. However, there is also a growing amount of evidence

that H2O2 signaling is required for many normal cellular

functions, including metabolic function [23, 24]. Because

our assays were performed using isolated mitochondria,

it is still possible that these findings are an artifact of the

experimental procedure. Thus, it would be of interest to

determine in vivo free radical production in living TgMito

MsrA mice to better define this potential relationship.

More broadly, our data aligns with an expanding number

of findings that seem to refute the oxidative stress theory

of aging, at least in murine models. While this theory

originally received much attention, in part due to its simplicity, support for it has been largely equivocal. Most

aging studies conducted in mice with genetically altered

enzymatic antioxidants have shown no consistent effect

on longevity [25]. Even in transgenic mice with mitochondrial-targeted antioxidant overexpression, there has been

little consensus as to their effect on lifespan [14, 26, 27].

On the other hand, aging is a biological process, and there

is clear interest in understanding how age-related changes

in health (and not just lifespan) might be regulated by

processes such as mitochondrial oxidative stress [28, 29].

In this regard, there is evidence that increased oxidative

stress drives multiple health deficits in mouse models of

aging [30, 31]. We have reported a potential aging benefit

of TgMito MsrA mice on metabolic function, while others

have shown these mice to not be protected from a cardiac

ischemia-reperfusion model [13, 14]. It would be of interest to take a more holistic approach toward functional

aging assessments to determine the role of mitochondrial

MsrA in the regulation of theaging process.

The actions of MsrA in the mitochondria may be beyond

that of the catalytic reduction of methionine sulfoxide.

There is a developing set of evidence that methionine oxidation can regulate protein function with stereo-specific

oxidation and reduction using methionine sulfoxide reductases as a key regulator [5, 6, 32]. In addition, an increasing amount of clues that MsrA directs protein degradation

through ubiquitin-like modifications suggest that MsrA

plays a far more central role in proteostasis than previously believed [8]. Moreover, the importance of methionine metabolism in regulating cellular homeostasis, for

example transsulfuration and hydrogen sulfide generation,

suggests methionine sulfoxide reductases could function

in a previously unrecognized pivotal regulatory mode for

maintaining normal cellular function and communication [33, 34].

Declarations

Acknowledgements

The animal care provided by the Department of Lab Animal Research (LAR) at UTHSCSA is acknowledged.

Availability of data and materials

This material is the result of work supported with resources and the use of facilities at South Texas Veterans Health Care System, San Antonio, Texas. The contents do not represent the views of the U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs or the United States Government.

Financial support and sponsorship

Research was supported by NIH R01 AG050797, R01 AG05431, a grant from the American Heart Association (15BGIA23220016) and a grant from the San Antonio Area Foundation. Effort was also supported in part by the San Antonio Nathan Shock Center for Excellence in the Biology of Aging (P30 AG013319) and the San Antonio Claude A. Pepper Older Americans Independence Center (P30 AG044271). ABS was also supported by the Geriatric Research, Education and Clinical Center of the South Texas Veterans Health Care System.

Conflict of interest

Adam Salmon is a member of the Editorial Board of Aging Pathobiology and Therapeutics. All authors declare no conflict of interest and were not involved in the journal’s review or desicions related to this manuscript.

References

1. Schmidt O , Pfanner N , Meisinger C . Mitochondrial protein import: from proteomics to functional mechanisms. Nature reviews Molecular cell biology, 2010, 11(9): 655- 667.

2. Bender A , Hajieva P , Moosmann B . Adaptive Antioxidant Methionine Accumulation In Respiratory Chain Complexes Explains The Use Of A Deviant Genetic Code In Mitochondria. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America, 2008, 105(43):16496-16501.

3. Moosmann B . Respiratory chain cysteine and methionine usage indicate a causal role for thiyl radicals in aging. Experimental Gerontology, 2011, 46(2-3):164-169.

4. Brot N , Weissbach L , Werth J , et al. Enzymatic reduction of protein-bound methionine sulfoxide. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 1981, 78(4):2155- 2158.

5. Lim JC , You Z , Kim G , et al. Methionine sulfoxide reductase A is a stereospecific methionine oxidase. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America, 2011.

6. Manta B , Gladyshev V N . Regulated methionine oxidation by monooxygenases. Free Radical Biology and Medicine, 2017:S0891584917300722.

7. Tarrago L , Kaya A , Weerapana E , et al. Methionine Sulfoxide Reductases Preferentially Reduce Unfolded Oxidized Proteins and Protect Cells from Oxidative Protein Unfolding. Journal of Biological Chemistry, 2012, 287(29):24448-24459.

8. Fu X , Adams Z , Liu R , et al. Methionine Sulfoxide Reductase A (MsrA) and Its Function in Ubiquitin-Like Protein Modification in Archaea. Mbio, 2017, 8(5):e01169-17.

9. Kaya A , Koc A , Lee B C , et al. Compartmentalization and regulation of mitochondrial function by methionine sulfoxide reductases in yeast. biochemistry, 2018, 49(39):8618-8625.

10. Dun Y , Vargas J , Brot N , et al. Independent roles of methionine sulfoxide reductase A in mitochondrial ATP synthesis and as antioxidant in retinal pigment epithelial cells. Free Radical Biology & Medicine, 2013, 65:1340- 1351.

11. Moskovitz J , Du F , Bowman C F , et al. Methionine sulfoxide reductase A (MsrA) affects beta-amyloid solubility and mitochondrial function in a mouse model of Alzheimer’s disease. american journal of physiology endocrinology & metabolism, 2016, 310(6):ajpendo.00453.2015.

12. Noh MR, Kim KY, Han SJ, et al. Methionine Sulfoxide Reductase A Deficiency Exacerbates CisplatinInduced Nephrotoxicity via, Increased Mitochondrial Damage and Renal Cell Death. Antioxidants & Redox Signaling:ars.2016.6874.

13. Zhao H , Sun J , Deschamps A M , et al. Myristoylated methionine sulfoxide reductase A protects the heart from ischemia-reperfusion injury. American Journal of Physiology Heart & Circulatory Physiology, 2011, 301(4):H1513-H8.

14. Salmon A B , Kim G , Liu C , et al. Effects of Transgenic Methionine Sulfoxide Reductase A (MsrA) Expression on Lifespan and Age-Dependent Changes in Metabolic Function in Mice. Redox Biology, 2016:S2213231716301987.

15. Styskal J, Nwagwu FA, Watkins YN, et al. Methionine sulfoxide reductase A affects insulin resistance by protecting insulin receptorfunction. Free Radical Biology and Medicine, 2013.

16. Hunnicut J L , Liu Y , Richardson A , et al. MsrA Overexpression Targeted to the Mitochondria, but Not Cytosol, Preserves Insulin Sensitivity in Diet-Induced Obese Mice. PLOS ONE, 2015, 10.

17. Pulliam D A , Deepa S S , Liu Y , et al. Complex IV Deficient Surf1-/- Mice Initiate Mitochondrial Stress Responses. Biochemical Journal, 2014, 462(2):359.

18. Lustgarten M S , Jang Y C , Liu Y , et al. Conditional knockout of Mn-SOD targeted to type IIB skeletal muscle fibers increases oxidative stress and is sufficient to alter aerobic exercise capacity. AJP: Cell Physiology, 2009, 297(6):C1520-C1532.

19. Gardner P R , Raineri I , Epstein L B , et al. Superoxide Radical and Iron Modulate Aconitase Activity in Mammalian Cells. Journal of Biological Chemistry, 1995, 270(22):13399-13405.

20. Rodney L, Levine, Laurent, et al. Methionine residues as endogenous antioxidants in proteins. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America, 1996, 93(26):15036-40.

21. Martin D R , Matyushov D V . Electron-transfer chain in respiratory complex I. Scientific Reports, 2017, 7(1).

22. Fazakerley D J , Minard A Y , Krycer J R , et al. Mitochondrial oxidative stress causes insulin resistance without disrupting oxidative phosphorylation. Journal of Biological Chemistry, 2018:jbc.RA117.001254.

23. Lee S, Tak E, Lee J, et al. Mitochondrial H2O2 generated from electron transport chain complex I stimulates muscle differentiation. Cell Research, 2011, 21(5):817-834.

24. Pi J , Bai Y , Zhang Q , et al. Reactive oxygen species as a signal in glucose-stimulated insulin secretion. Diabetes, 2007, 56(7):1783-1791.

25. Edrey Y H , Salmon A B . Revisiting an age-old question regarding oxidative stress. Free Radical Biology and Medicine, 2014, 71.

26. Cunningham G M , Flores L C , Roman M G , et al. Thioredoxin overexpression in both the cytosol and mitochondria accelerates age-related disease and shortens lifespan in male C57BL/6 mice. Geroscience, 2018.

27. Schriner SE, Linford NJ, Martin GM, et al. Extension of murine life span by overexpression of catalase targeted to mitochondria. Science. 2005, 308(5730):1909-11.

28. Matt K . How healthy is the healthspan concept?. GeroScience, 2018:s11357-018-0036-9.

29. Davies JMS, Cillard J, Friguet B, et al. The Oxygen Paradox, the French Paradox, and age-related diseases. GeroScience. 2017, 39(5-6):499-550.

30. Deepa S S , Bhaskaran S , Espinoza S , et al. A new mouse model of frailty: the Cu/Zn superoxide dismutase knockout mouse. GeroScience, 2017, 39(2):187-198.

31. Snider T A , Richardson A , Stoner J A , et al. The Geropathology Grading Platform demonstrates that mice null for Cu/Zn-superoxide dismutase show accelerated biological aging. GeroScience, 2018, 40(2):97-103.

32. Lee B , Péterfi, Zalán, Hoffmann F K , et al. MsrB1 and MICALs Regulate Actin Assembly and Macrophage Function via Reversible Stereoselective Methionine Oxidation. Molecular Cell, 2013, 51(3):397-404.

33. Olecka M, Huse K, Platzer M. The high degree of cystathionine beta-synthase (CBS) activation by S-adenosylmethionine (SAM) may explain naked mole-rat’s distinct methionine metabolite profile compared to mouse. GeroScience, 2018.

34. Lee H J , Feliers D , Barnes J L , et al. Hydrogen sulfide ameliorates aging-associated changes in the kidney. Geroence, 2018, 40(2):163-76.