Open Access | Case Report

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-ShareAlike 4.0 International License.

Genital auto-mutilation, the second attempt was dramatic

*Corresponding author: Nedjim Abdelkerim Saleh

Mailing address: Department of Urology, Ibn Rochd University

Hospital and Faculty of Medicine and Pharmacy, Casablanca, Morocco.

E-mail: nedjimsaleh@gmail.com

Received: 26 February 2020 / Accepted: 20 April 2021

DOI: 10.31491/CSRC.2021.06.072

Abstract

Genital auto-mutilation is a urological emergency rarely encountered in practice. It constitutes a drama by its manner of occurrence and clinical presentation. In case of heavy bleeding, a state of hemorrhagic shock may occur and require resuscitation. the treatment is based on surgery and psychiatric advice. a regular follow-up with an attentive intention is needed to avoid the recurrency. We are reporting a 29-year-old patient followed for schizophrenia with poor compliance who is attempting genital auto-mutilation for the second time. The first attempt resulted in shallow wounds, but the second attempt was dramatic: it resulted in genital amputation.

Keywords

Penis, external genital organs, mutilation, amputation, schizophrenia

Introduction

Self-injury is defined as an intentional act on one’s organs without a suicidal intention [1]. Genital auto-mutilation is one of the rare and more complex forms, both psychopathologically and symbolically [2]. It constitutes a serious urological emergency [3]. The prognosis is marked by the repercussions on the psycho-social level, then those on the urinary and sexual functions of the organ [4]. The authors report a new observation of self-mutilation in a schizophrenic patient with a history of attempted genital auto-mutilation.

Case Report

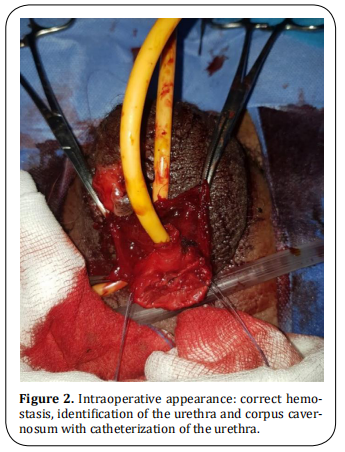

A 29-year-old patient, followed for schizophrenia for 2 years on neuroleptics treatments with poor compliance who has attempted to amputate his testicles a week earlier brought once again to the emergency department by his family following auto--amputation of his penis in the toilet approximately some hours before the admission. The clinical examination revealed a calm patient in hemorrhagic shock with an amputated penis at its base, active bleeding, and a scrotal wound in the process of healing (Figure 1). Hemostatic measurements were taken in the emergency room and the patient was taken to the intensive care unit for resuscitation. After stabilization, he was referred to the operating room. After thorough washing with saline and antiseptic, perfect control of the hemostasis was ensured with identification of the urethra and the corpus cavernosum. A bladder catheterization was easily performed with a foley catheter 18 (Figure 2). The final gesture consisted of a urethrostomy, placement of a drain, and suturing of the different planes (Figure 3). The postoperative follow-up was simple. The patient is regularly followed up with his psychiatrist.

Discussion

Genital self-mutilation is a urological emergency rarely

encountered in practice. It constitutes a drama by its

manner of occurrence and its clinical presentation. In

case of heavy bleeding, a state of hemorrhagic shock

may set in and require resuscitation. The mainstay of

treatment is emergency surgery and psychiatric advice. This follow-up must be regular and assess an intention of recurrence. Beyond the functional prognosis

(micturition and sexual), there is a problem with body

image.

Penile amputation has been classified into three

groups: self-mutilation, criminal amputation, and traumatic accident [5]. Self-mutilation, an unusual situation

in daily urological practice, is a rare phenomenon. It

occurs in the majority of cases in a psychotic setting

but can be secondary to drug or alcohol abuse. Treatment and management vary according to the severity

of the lesions, the time required for consultation, and

the mental state of the patient [6].

The man has an ambivalent relationship with his body.

As an object of care, revered, the body can also be the

site of mutilating practices. Men have always marked

their bodies in ritual practices [7]. Self-mutilation would

be reported in mythology, ethnology, and some religious and contemporary rituals [2]. The first self-castration in history is reported by Lucien of Samosata who

relates the legendary story of Combatus. He is a young

Syrian of great beauty who had received from his king

the important mission to accompany Queen Stratonice

on her journey to Hierapolis in Phrygia. He decided to

emasculate himself before the departure and to lock

his genitals in a box that he entrusted to the king. This

sacrifice enabled him to confound his slanderers on his

return and was worth to him to be filled with honors

by the king [8].

The incidence of this disease is not well known, the

majority of cases do not seem to be reported by the

patient or the family [9]. Black et al. identified three

particular groups at risk for genital self-harm: schizophrenics, transvestites, and men with religious or cultural conflicts [10].

The current standard of treatment for this infrequent

injury is replanting with the approximation of the

urethra, corpus cavernosum, and microsurgical anastomosis of the dorsal vein, arteries, and nerves. This

technique is considered to reduce immediate and longterm postoperative complications [11]. Certain conditions are necessary to replant the amputated penis and

predict the success of the surgery: state of the viability

of the organ, state of the graft bed, or stump of the penis at the time of injury. The amputated part must be

wrapped in gauze soaked in saline solution and placed

in a sterile bag [12]. If reimplantation is not possible, hemostasis with skin ureterostomy is performed [13].

In our context, given the contexts in which the procedure occurred and the time of presentation, we were

unable to attempt reimplantation. Our attitude was,

first of all, to stabilize the patient and transport him to

the operating room with perfect control of hemostasis,

regularization of the stump, and urethrostomy.

Conclusion

Self-mutilation of the penis is a rare situation in urological practice. It frequently occurs in schizophrenia. The management is multidisciplinary and may involve the resuscitator, the urologist, and the psychiatrist. The surgical attitude in an emergency depends on the severity of the lesions and the time of consultation. It must be done to preserve the functions of the penis as much as possible.

Declarations

Authors’ contributions

All the authors contributed substantially to the design and production of this article.

Conflicts of interest

All authors declared that there are no conflicts of interest.

Ethics approval

Not applicable.

References

1. Favazza, A. R. (1998). The coming of age of self-mutilation. The Journal of nervous and mental disease, 186(5),

259-268.

2. Outarahout, M., & Sekkat, F. Z. (2014). Automutilation de la verge ou le suicide de genre. Trois cas de

schizophrènes. L’information psychiatrique, 90(3), 207-

211.

3. Caygill, P. L., Floyd Jr, M. S., New, F. J., & Davies, M. C. (2018).

A successful microsurgical approach to treating penile

amputation following genital self mutilation. Journal of

surgical case reports, 2018(10), rjy271.

4. Patial, T., Sharma, G., & Raina, P. (2017). Traumatic penile

amputation: a case report. BMC urology, 17(1), 1-4.

5. Jezior, J. R., Brady, J. D., & Schlossberg, S. M. (2001). Management of penile amputation injuries. World journal of

surgery, 25(12), 1602-1609.

6. Jezior, J. R., Brady, J. D., & Schlossberg, S. M. (2001). Management of penile amputation injuries. World journal of

surgery, 25(12), 1602-1609.

7. Morelle, C. (1995). Le corps blessé: automutilation, psychiatrie et psychanalyse. FeniXX.

8. Androutsos, G., & Geroulanos, S. (2001). L’eunuchisme à

Byzance. Progrès en urologie (Paris), 11(4), 757-760.

9. Hendershot, E., Stutson, A. C., & Adair, T. W. (2010). A

Case of Extreme Sexual Self-Mutilation. Journal of forensic sciences, 55(1), 245-247.

10. Blacker, K. H., & Wong, N. (1963). Four cases of autocastration. Archives of General Psychiatry, 8(2), 169-169.

11. Abaka, N., Ghoundale, O., & Touiti, D. (2013). Genital self amputation or the Klingsor syndrome: Successful nonmicrosurgical penile replantation. Urology annals, 5(4),

305.

12. Hayhurst, J. W., McC. O’BRIEN, B., Ishida, H., & Baxter, T.

J. (1974). Experimental digital replantation after prolonged cooling. Hand, 6(2), 134-141.

13. Sarr, A., Sow, Y., Ndiaye, B., Koldimadji, M., Ouedraogo, B.,

Diao, B., ... & Diagne, B. A. (2015). Automutilation génitale

masculine: à propos de 2 observations. Sexologies, 24(2),

65-68.