Open Access | Research article

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-ShareAlike 4.0 International License.

Intestinal Resection in Children: An Experience in Enugu, Nigeria

*Corresponding author: Chukwubuike Kevin Emeka

Mailing address: Department of Surgery, Enugu State University

Teaching Hospital, Enugu, Nigeria.

Email: chukwubuikeonline@yahoo.com

Received: 31 December 2019 Accepted: 09 January 2020

DOI: 10.31491/CSRC.2020.03.045

Abstract

Background: Intestinal resection in children is an important surgical procedure because of the possible complications that may arise from it. Late presentation and ignorance in developing countries have made intestinal resection a frequent surgical procedure.

Methods: This was a retrospective study of children that had intestinal resection in the pediatric surgery unit of Enugu State University Teaching Hospital, Enugu, Nigeria. The medical records of the pediatric patients that underwent intestinal resection over a 10-year period were evaluated for the indications that prompted the surgery. The other parameters that were assessed included the patients’ demographics, the duration of symptoms before presentation, the time interval between presentation and intervention, the complications arising from the intestinal resection, and the outcome.

Results: There were 52 cases of intestinal resection with an age range of 1–168 months (median 10 months) and a male to female ratio of 2.25:1. There were 9 neonates (less than one month of age), 29 infants (greater than one month but less than one year of age) and 14 children (older than 1 year of age). The following were the indications for intestinal resection: gangrenous/irreducible intussusception (28 or 53.8%), strangulated external hernia (7 or 13.5%), typhoid intestinal perforation (6 or 11.5%), intestinal atresia (3 or 5.8%), gastroschisis (3 or 5.8%), midgut volvulus (3 or 5.8%), and abdominal trauma (2 or 3.8%). The following definitive surgical procedures were performed: right hemicolectomy with ileotransverse anastomosis (28 or 53.8%), segmental resection with end-to-end anastomosis (20 or 38.5%), and massive intestinal resection with end-to-end anastomosis (4 or 7.7%). The median duration of symptoms prior to presentation and the median duration from presentation to surgery were 3 days and 2 days, respectively. The mean duration of hospital stay was 15 days. Twenty patients (38.4%) developed complications, which included surgical site infection (8 or 15.4%), enterocutanous fistula (6 or 11.5%), intra-peritoneal abscess (4 or 7.7%), and adhesive intestinal obstruction (2 or 3.8%). There were 8 deaths, which accounted for 15.4% of the patients.

Conclusion: Intestinal resection was performed most often for intussusception. Late presentation and ignorance contributed significantly to the number of intestinal resections required.

Keywords

Children; intestinal resection; experience; intussusception; hernia

Introduction

In carrying out their duties, pediatric surgeons often undertake intestinal resections in children as part of the treatment of their patients. There is a wide range of indications for intestinal resection, and these indications range from congenital to acquired anomalies. In a resource-poor setting like ours, the indications for intestinal resection are mostly for acquired and preventable diseases. However, publications from high-income countries have reported that congenital anomalies were the most common indication for intestinal resection [1, 2, 3]. There has not been any published report of intestinal resection in children from our center. In this study, we reviewed our experience with intestinal resection in children over a 10-year period at Enugu State University Teaching Hospital (ESUTH), Enugu, Nigeria. We evaluated the indications, complications, and outcomes of pediatric intestinal resection. This study will help identify the challenges encountered in the management of these patients and proffer possible solutions.

Methodology

This was a retrospective study of children aged 15 years and below who had an intestinal resection procedure between September 2008 and October 2018 in the pediatric surgery unit of ESUTH, Enugu, Nigeria. Patients who had undergone intestinal resection for the same pathology at a peripheral hospital before referral to ESUTH for reoperation were excluded from this study. ESUTH is a tertiary hospital located in Enugu, South East Nigeria. The hospital serves the whole of Enugu State, which, according to the 2016 estimates of the National Population Commission and Nigerian National Bureau of Statistics, has a population of about 4 million people and a population density of 616.0/km2. The hospital also receives referrals from its neighboring states. Information was extracted from the case notes, operation notes, operation register, and admission-discharge records. The information extracted included age, gender, duration of symptoms before presentation, time interval between presentation and intervention, indication for intestinal resection, definitive operative procedure performed, complications, duration of hospital stay, and outcome of treatment. The follow-up period was 6 months. Ethical approval was obtained from the ethics and research committee of ESUTH. The Statistical Package for the Social Science (SPSS) version 21, manufactured by IBM Corporation Chicago Illinois, was used for data entry and analysis. Data were expressed as percentages, median, mean, and range.

Results

Patients’ demographics

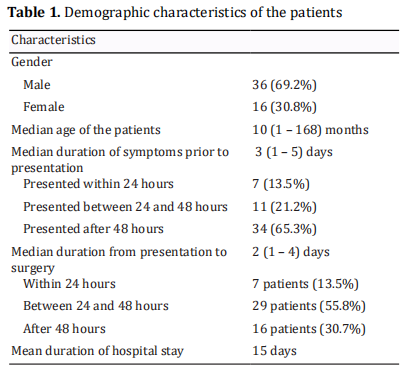

Sixty-two intestinal resections were performed during the study period, but only 52 cases had complete case records and formed the basis of this report. There were 36 males (69.2%) and 16 females (30.8%), which corresponds to a male to female ratio of 2.25:1. The ages of the patients ranged from 1 to 168 months, with a median of 10 months. Sixty-five percent of the patients were less than 12 months of age. The median duration of symptoms prior to presentation to the hospital was 3 (1 – 5) days. Seven patients (13.5%) presented within 24 hours of the onset of their symptoms, while eleven patients (21.2%) presented between 24 and 48 hours. Thirty-four patients (65.3%) presented after more than 48 hours had elapsed since the onset of their symptoms. The median duration from presentation to surgery was 2 (1 – 4) days. Most of the patients (69.3%) were operated on within 48 hours of presentation to the hospital. The mean duration of hospital stay was 15 days. These statistics are shown in Table 1.

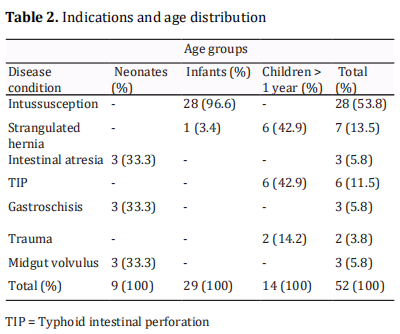

Indications and age distribution of the patients

The various indications for intestinal resection and their corresponding age distributions are shown in Table 2.

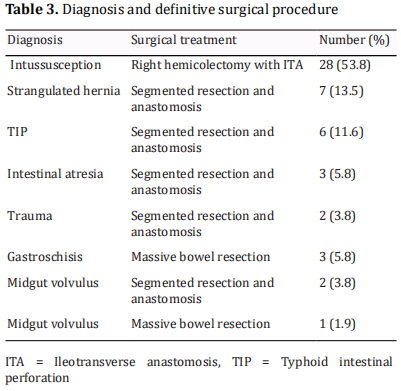

Definitive operation performed

Right hemicolectomy with ileotransverse anastomosis was the most commonly performed definitive surgery(28 or 53.8%), followed by segmental resection with end-to-end anastomosis (20 or 38.5%), and massive intestinal resection with end-to-end anastomosis (4 or 7.7%). These details are shown in Table 3.

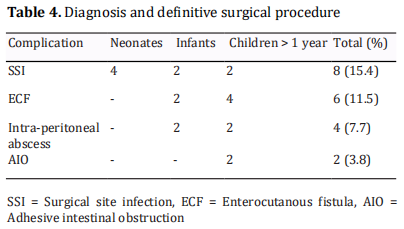

Complications following intestinal resection

The majority of the patients (61.6%) did not develop any complications. The most common complication was surgical site infection, which developed in 8 patients (15.4%). The other complications are shown in Table 4.

Outcome

Forty-two patients (80.8%) did well and were discharged home. Two patients (3.8%) signed out against medical advice in the post-operative period. Mortality was recorded in 8 patients (15.4%). Mortality occurred mostly among neonates.

Discussion

Acquired and preventable diseases account for the majority of the intestinal resections performed in children in developing countries [4]. The potential morbidity and mortality associated with intestinal resection make it an important surgical procedure [1]. Massive intestinal resection may result in short bowel syndrome when the functioning gut mass is reduced below the amount necessary for adequate digestion and absorption of fluids and nutrients [5].

The male dominance reported in the current study was consistently observed in other studies as well [1, 3, 4, 6]. The median age of 10 months of our patients is similar to reports by Ezomike et al. and Ajao et al. [4, 5]. However, a study conducted in northern Nigeria reported a median age of 6 years. The differences in the median ages of the patients may be explained by the geographical area of the study where different diseases are predominant. For instance, Ameh reported typhoid intestinal perforation as the most common indication for intestinal resection, whereas, in our study, we recorded intussusception as the most common indication. The late presentation of our patients is manifested in the median duration of 3 days prior to presentation to the hospital. This finding is consistent with other reports [4, 6]. It is noteworthy that this late presentation is common in developing countries, which may be due to poverty and ignorance [7]. Early presentation reduces the rate of intestinal resection [8]. In developed countries, the majority of children are hospitalized within 24 hours of onset of their symptoms [9, 10]. The average time to intervention of 48 hours reported in the current study is consistent with the report by Ezomike et al. [4]. The length of hospitalization of 15 days is in line with the results of previous studies [3, 4]. However, Ameh reported a longer duration of hospital stay in his patients. In their study of childhood intussusception, Chalya et al. reported that the length of hospital stay was longer in children who had intestinal resection when compared with those who had no resection [11].

In the current study, intussusception was the most common indication for intestinal resection. This finding is in accordance with the results of previous studies [3, 4, 6, 12, 13]. However, it is in contrast with a report from Zaria, Nigeria that reported typhoid intestinal perforation as the most common indication for intestinal resection [1]. The reason for this difference is not exactly known, but it may be explained by the locations of the studies and their prevalent disease patterns. The low incidence of typhoid intestinal perforation as an indication for bowel resection in the current study may reflect the lower incidence of typhoid fever in the area being studied [14]. The majority of our patients had right hemicolectomy with ileotransverse anastomosis. This finding is supported by the reports of other studies [4, 6]. However, another study reported segmental ileal resection as the most common surgical procedure [1]. Studies conducted in northern Nigeria showed that segmental ileal resection was the most effective treatment modality for typhoid ileal perforation [15, 16]. The definitive surgical treatment offered to patients who undergo intestinal resection depends on their disease condition. All 4 of our patients that received massive bowel resection had extensive bowel gangrene secondary to gastroschisis. Our complication rate is comparable to the results of other similar studies [4, 6]. The complication rate following intestinal resection can be as low as 26% [1]. Post-operative complication rates vary widely, and the occurrence of surgical site infection involves a complex interaction between several factors, including microbial, patient, surgical, environmental, healthcare facility, and procedure performed [17, 18]. The mortality rate in the current study appears to be the average of what other researchers have recorded; published mortality ranges from 5.5% to 31.8% [1, 4, 6].

Conclusion

In the present study, gangrenous/irreducible intussusception was the most common indication for intestinal resection. Early presentation and awareness of the clinical conditions by the parents and medical practitioner may have prevented some of these intestinal resections.

Declarations

Authors’ contribution

The author contributed solely to this article.

Availability of data and materials

Data is available with the author and can be provided on request.

Conflict of interest

The author declares that there is no conflict of interest.

Ethical approval

Ethical approval was obtained from the hospital ethics committee.

References

1. E A Ameh. (2001). Bowel resection in children. East

African Medical Journal, 78(9), 477-479.

2. Rubén E. Quirós-Tejeira, Ament, M. E. , Reyen, L. , Herzog,

F. , Merjanian, M. , & Olivares-Serrano, N. , et al. (2004).

Long-term parenteral nutritional support and intestinal

adaptation in children with short bowel syndrome: a 25-

year experience. Journal of Pediatrics, 145(2), 0-163.

3. Abdur-Rahman, L. O., Adeniran, J. O., Taiwo, J. O., Nasir,

A. A., & Odi, T. (2009). Bowel resection in Nigerian

children. African Journal of Paediatric Surgery, 6(2), 85.

4. Ezomike, U. O., Ituen, M. A., & Ekpemo, C. S. (2014).

Indications and outcome of childhood preventable bowel

resections in a developing country. African Journal of

Paediatric Surgery, 11(2), 97.

5. Weale, A. R., Edwards, A. G., Bailey, M., & Lear, P. A.

(2005). Intestinal adaptation after massive intestinal

resection. Postgraduate medical journal, 81(953), 178-

184.

6. A, E, Ajao, T, A, & Lawal, et al. (2019). Bowel resection in

children in ibadan, nigeria. Journal of the West African

College of Surgeons, 8(1), 56-61.

7. Ekenze, S. O., & Mgbor, S. O. (2011). Childhood

intussusception: the implications of delayed

presentation. African Journal of Paediatric Surgery, 8(1),

15.

8. Ogundoyin, O. O., Olulana, D. I., & Lawal, T. A. (2016).

Childhood intussusception: Impact of delay in presentation

in a developing country. African journal of paediatric

surgery: AJPS, 13(4), 166.

9. Latipov, R., Khudoyorov, R., & Flem, E. (2011). Childhood

intussusception in Uzbekistan: analysis of retrospective

surveillance data. BMC pediatrics, 11(1), 22.

10. Buettcher, M., Baer, G., Bonhoeffer, J., Schaad, U. B.,

& Heininger, U. (2007). Three-year surveillance of

intussusception in children in Switzerland. Pediatrics, 1

20(3), 473-480.

11. Chalya, P. L., Kayange, N. M., & Chandika, A. B. (2014).

Childhood intussusceptions at a tertiary care hospital

in northwestern Tanzania: a diagnostic and therapeutic

challenge in resource-limited setting. Italian journal of

pediatrics, 40(1), 28.

12. Rao, P. L., Sharma, A. K., Yadav, K., Mitra, S. K., & Pathak, I.

C. (1978). Acute intestinal obstruction in children as seen

in north west India.Indian pediatrics,15(12), 1017-1023.

13. Nmadu, P. T. (1992). The changing pattern of infantile

intussusception in Northern Nigeria: a report of 47

cases. Annals of tropical paediatrics, 12(4), 347-350.

14. Emeka, C. K., Chukwuebuka, N. O., Kingsley, N. I., Arinola, O.

O., Okwuchukwu, E. S., & Chikaodili, E. T. (2019). Paediatric

Abdominal Surgical Emergencies in Enugu, South East

Nigeria: Any Change in Pattern and Outcome. European

Journal of Clinical and Biomedical Sciences, 5(2), 39-42.

15. Ameh, E. A., Dogo, P. M., Attah, M. M., & Nmadu, P. T.

(1997). Comparison of three operations for typhoid

perforation. British journal of surgery, 84(4), 558-559.

16. Ameh, E. A. (1999). Typhoid ileal perforation in children:

a scourge in developing countries. Annals of tropical

paediatrics, 19(3), 267-272.

17. Cheadle, & William G. . Risk factors for surgical site

infection. Surgical Infections, 7(s1), s7-s11.

18. Pathak, A., Saliba, E. A., Sharma, S., Mahadik, V. K., Shah, H.,

& Lundborg, C. S. (2014). Incidence and factors associated

with surgical site infections in a teaching hospital in

Ujjain, India. American journal of infection control, 42(1),

e11-e15.