Open Access | Case Report

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-ShareAlike 4.0 International License.

Acute massive gastric dilatation: a surgical emergency

*Corresponding author: Dr. Parthasarathi Hota

Mailing address: Department of General Surgery, Calcuta Natonal Medical College, Gorachand Road, Kolkata – 700014, India.

Email: psh1011@rediffmail.com

Received: 10 September 2019 Accepted: 25 October 2019

DOI: 10.31491/CSRC.2019.12.043

Abstract

A 40 year old patient presents with acute pain abdomen with abdominal distension. History of unusual heavy meal one day before and following which symptoms appear. Few episodes of vomiting were associated. Resuscitation done. Straight x ray shows dilated gastric shadow. Patient posted for laparotomy after failing of conservative measures. On opening abdomen, hugely distended stomach seen with thinned out gastric wall and patchy areas of discolouration. A side to side gastrojejunostomy done after decompression on the dependent stomach. Post-operative recovery was uneventful. Psychological evaluation did not reveal any abnormality. Acute gastric dilatation can cause mucosal necrosis and gastric perforation therefore early diagnosis and gastric decompression is the key. Though most patients respond to conservative measures, failing which surgical decompression is needed.

Keywords

Acute gastric dilatation; eating disorders; gastric decompression; gastrojejunostomy; acute massive gastric dilatation

Introduction

Acute gastric dilatation [AGD] is a rare disorder with

most of the references in the literature as case reports.

AGD is encountered most often as a postoperative complication in abdominal surgery and in a multitude of

disorders, such as anorexia and bulimia nervosa, psychogenic polyphagia, trauma, diabetes mellitus etc. [1-5].

Acute massive gastric dilatation [AMGD] is the extreme

form of AGD. In literature the demarcation of AGD and

AMGD is not clearly mentioned. When the stomach is

extremely distended occupying the abdomen from

diaphragm to pelvis and from left to right, the AGD is

referred to as AMGD. Most frequently AMGD requires

surgical intervention to prevent or to treat gastric necrosis [3].

We present a case of acute massive gastric dilatation

with thinned out gastric wall but without perforation.

After failure of conservative measures, the patient was

treated surgically.

Case Report

A 40 year old male patient came to the emergency department at night with complaints of acute abdominal

pain and distension, multiple episodes of vomiting and

obstipation for 2 days.

The patient was apparently well until 2 days ago when

after having an unaccustomed heavy lunch he started

complaining of abdominal distension which was not

relieved by any means but aggravated with food and

fluid intake. The distension progressed gradually with

abdominal pain and multiple episodes of vomiting. The

vomitus comprised of food materials, non- bilious, nonprojectile and vomiting did not relieved the distension.

There was no history of hematemesis or fever. There

was history of obstipation for which he received enema

at the primary health centre, referred thereafter to our

hospital.

The patient had no history of alcohol/tobacco addiction.

He had normal bowel and bladder habits with one episode of binge eating two days ago. There was no history

of any chronic illness like diabetes or hypertension. He

was not taking any medication and did not undergo any

surgery before.

On general examination, the patient had no signs of anaemia, oedema, jaundice, clubbing or cyanosis. He was of

average built and nutritional status. At the time of admission his pulse was 110 per minute and blood pressure

was 110/70 mmHg.

On local examination, the abdomen was hugely distended with no dilated veins, scar mark and the umbilicus

everted. There was generalised tenderness. There was

no ascites or any abdominal lump. There was moderate amount of guarding and rigidity but no rebound tenderness.

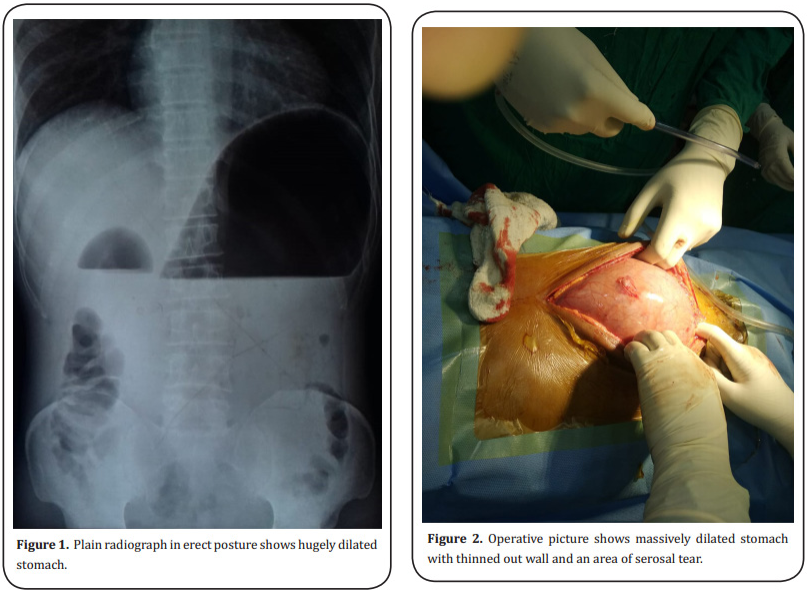

After admission the patient was resuscitated with normal saline and urgent upright abdominal x-ray was

done. The x-ray shows grossly dilated stomach (Figure

1) but there was no evidence of free gas under the diaphragm. A large bore nasogastric tube was inserted

and careful suctioning done. Scanty food materials and

fluid came out but then the material stopped coming

out of the stomach. The nasogastric tube repositioned

and changed but still without any yield. Then the NG tube was subjected to continuous vacuum suction pump

but still nothing evacuated. The abdominal distension

did not improve and the patient’s condition gradually

worsened. The abdominal pain was not relieved either.

At this stage conservative measures abandoned and the

patient was posted for emergency laparotomy after taking high risk consent. Standard midline vertical incision

given. As soon as the peritoneum opened, hugely distended stomach was seen extending from xiphisternum

to below umbilicus going towards the pelvis. The stomach wall was thinned out but there was no perforation

or obvious necrosis but a few patchy areas of slightly

dusky discolouration seen with one area of serosal tear (Figure 2). There was no rotation of the stomach and the

rest of the bowel was normal. Liver, spleen was normal,

there was no fluid inside the peritoneal cavity and no

other lump noted.

Posterior, retrocolic, isoperistaltic side to side gastro-jejunostomy done in two layers incorporating the gastrotomy. Primary repair done for the serosal tear with absorbable suture.

Full psychological evaluation of the patient done in the post-operative period but no abnormality including any eating disorders was found.

The recovery was uneventful with the patient passing flatus on third day and discharged on satisfactory condition after 7 days. Upper GI endoscopy was performed after 6 weeks and it shows normal gastric mucosa and with good and healthy anastomosis and no other abnormal finding.

Discussion

In 1833, Duplay first described acute gastric dilatation

[1]. Acute ischemic necrosis of stomach is a very rare disease due to its abundant vascular supply. In experimental

animals, in order to produce ischemic necrosis, closure

of the right and left gastric and gastroepiploic arteries

together with at least 80% blockage of the collaterals

is required [2]. The important causes are postoperative

complications [3, 4], anorexia nervosa and bulimia, psychogenic polyphagia, diabetes mellitus, trauma, electrolyte

disturbances, gastric volvulus, and spinal conditions [1,

5–10].

Our patient was of average built and nutrition. He was

not anorexic and psychological evaluation did not reveal

any abnormality. He was non diabetic and there was no

history of any other chronic illness or any prior surgery.

He had one binge eating episode about 48 hours ago. Afterwards he developed the symptoms and was admitted

in a primary health centre from where the patient was

referred to our institution.

Ischemia is caused presumably due to venous insufficiency when massive dilatation occurs [11, 12]. To impair

venous return, either 14mmHg of pressure or more than

3 litres of fluid is sufficient, although more than 15 litres has been described in eating disorders in chronic

distension.

Rupture can occur with intragastric pressures of more

than 120mmHg or 4 litres of fluid. In the majority of the

cases, greater curvature and gastric fundus are more

prone for necrosis and require emergent treatment [13].

Lesser curvature and pyloric regions of the stomach tend

to be spared [1].

A consequence of events as postulated by Abdu et al. is

mucosal necrosis, followed by full-thickness involvement

of the gastric wall and perforation [10–12]. Surgery may be

avoided if the diagnosis is established in an early stage. A

mortality rate of 80% to 100% has been reported due to

gastric ischemia and perforation as a result of dilation [14].

In our case, the stomach was hugely dilated and the greater curvature was below the umbilicus going towards the

pelvis. The gastric wall was thinned out and few patchy

areas of discolouration seen. No definite area of full

thickness gastric wall necrosis seen. There was one area

of serosal damage with impending perforation seen on

the body of the stomach. Patient received naso gastric

suction at the primary health centre which we believe

although failed to relieve the patient, but prevented the

rise of intra-gastric pressure to very high level and causing full thickness necrosis of the stomach.

Several theories have been postulated to explain the

pathogenesis of acute gastric dilatation. Morris et al.

claimed that anaesthesia and debilitation may be predisposing factor as it is a very frequent postoperative complication. Relaxation of the upper oesophageal sphincter with aerophagia may be a factor leading to gastric

distention [3, 4, 10]. In 1859, Brinton introduced the atonic

theory [10]. The stomach undergoes atony and muscular

atrophy during a period of starvation, so that a sudden

ingestion of food overtaxes an already weakened stomach in patients with eating disorders. In 1861, von Rokitansky proposed superior mesenteric artery syndrome

(mechanical theory) in which vascular compression of

the third segment of the duodenum, between superior

mesenteric artery, aorta, and vertebral column, causes

acute gastric dilatation [5]. Other authors suggest that

pancreatitis, peptic ulcer, gallbladder disease, and appendicitis also cause acute gastric dilatation [15, 16] and

infectious causes like necrotizing gastritis generally

involving immunocompromised patients like diabetes,

AIDS, and neoplasia are also reported [17, 18].

In more than 90% of cases of acute gastric dilatation,

vomiting is an important and common symptom [19]. Another sign reported in the literature is the inability to

vomit which is not fully understood. This may be due

to the occlusion of the gastroesophageal junction by the

distended.

Fundus, which angulates the oesophagus against the

right crus of the diaphragm, producing a one-way valve

[20]. Significant, diffuse abdominal distension accompanied by abdominal pain is common.

Plain abdominal radiograph and CT scan can demonstrate gastric distension and free air if present. In this

patient plain abdominal radiographs revealed grossly

distended stomach but no free air. As the patient was

not improving with conservative measures and he was

clinically deteriorating, we opted for emergency laparotomy fearing imminent perforation or necrosis. Treatment focuses on early diagnosis and decompression of

the stomach, thus halting the vascular congestion and

thus ischemia [21].Decompression with nasogastric tube

should be the first step in the management, followed by

immediate surgery in case of perforation. A normal size

nasogastric tube may prove to be inefficient in decompressing stomach. Sometimes, when semisolid material

is present in the stomach, even a large tube may be inefficient. In our case too since the contents were semisolid nasogastric tube was non-productive. If conservative

measures fail or gastric infarction with or without perforation is suspected, immediate surgical intervention

is mandatory [10].

We performed a gastrotomy for proper decompression

of the stomach near the greater curvature at the most dependent part and after decompressing, we performed a

side to side, two layered gastrojejunostomy. Primary repair done of the small area of serosal damage. We believe

that, in this condition a drainage procedure was better

than simple closure of the gastrotomy wound in view of

preventing recurrence. It has been reported to perform

partial or even total gastrectomy depending on the area

of the necrosis and general condition of the patient.

Surgeons should be aware that acute gastric dilatation

may occur even in patients who are not diagnosed as

having a typical eating disorder after an unaccustomed

episode of binge eating. A high index of suspicion is

necessary to diagnose this condition in order to avoid fatal complications. First line of treatment should be

conservative with nasogastric decompression. If it fails,

necessary timely surgery would prevent unnecessary

morbidity.

Declaration

Conflicts of interest

Te authors declare that there is no conflict of interest among the authors regarding publication of this paper.

References

1. Todd, S. R., Marshall, G. T., & Tyroch, A. H. (2000). Acute

gastric dilatation revisited. The American Surgeon, 66(8),

709.

2. T H SOMERVELL. (1945). Physiological gastrectomy. British Journal of Surgery, 33(1), 146-152.

3. Byrne, J. J., & Cahill, J. M. (1961). Acute gastric dilatation, 101(3), 301-309.

4. Cogbill, T. H., Bintz, M. A. R. I. L. U., Johnson, J. A., & Strutt,

P. J. (1987). Acute gastric dilatation after trauma. The Journal of trauma, 27(10), 1113-1117.

5. Adson, D. E., Mitchell, J. E., & Trenkner, S. W. (1997). The

superior mesenteric artery syndrome and acute gastric

dilatation in eating disorders: a report of two cases and

a review of the literature. International Journal of Eating

Disorders, 21(2), 103-114.

6. Turan, M., Şen, M., Canbay, E., Karadayi, K., & Yildiz, E.

(2003). Gastric necrosis and perforation caused by acute

gastric dilatation: report of a case. Surgery today, 33(4),

302-304.

7. Jefferiss, C. D. (1972). Spontaneous rupture of the stomach in an adult. British Journal of Surgery, 59(1), 79-80.

8. Wharton, R. H., Wang, T., Graeme-Cook, F., Briggs, S., &

Cole, R. E. (1997). Acute idiopathic gastric dilatation

with gastric necrosis in individuals with Prader-Willi

syndrome. American journal of medical genetics, 73(4),

437-441.

9. Evans, D. S. (1968). Acute dilatation and spontaneous rupture of the stomach. British Journal of Surgery, 55(12),

940-942.

10. Abdu, R. A., Garritano, D., & Culver, O. (1987). Acute gastric necrosis in anorexia nervosa and bulimia: two case

reports. Archives of Surgery, 122(7), 830-832.

11. Mishima, T., Kohara, N., Tajima, Y., Maeda, J., Inoue, K., Ohno,

T., ... & Kuroki, T. (2012). Gastric rupture with necrosis following acute gastric dilatation: report of a case. Surgery

today, 42(10), 997-1000.

12. Lunca, S., Rikkers, A., & Stãnescu, A. (2005). Acute massive

gastric dilatation: severe ischemia and gastric necrosis

without perforation. Rom J Gastroenterol, 14(3), 279-283.

13. Kerstein, M. D., Goldberg, B., Panter, B., Tilson, M. D.,

& Spiro, H. (1974). Gastric infarction. Gastroenterology, 67(6), 1238-1239.

14. Koyazounda, A., LeBaron, J. C., Abed, N., Daussy, D., Lafarie,

M., & Pinsard, M. (1985). Gastric necrosis from acute gastric dilatation: recovery after total gastrectomy. Journal de

Chirurgie, 122(6-7), 403-407.

15. Backett, S. A. (1985). Acute pancreatitis and gastric dilatation in a patient with anorexia nervosa. Postgraduate

Medical Journal, 61(711), 39-40.

16. Gondos, B. (1977). Duodenal compression defect and

the “superior mesenteric artery syndrome”. Radiology, 123(3), 575-580.

17. Nagai, T., Yokoo, M., Tomizawa, T., & MORI, M. (2001). Acute

gastric dilatation accompanied by diabetes mellitus. Internal Medicine, 40(4), 320-323.

18. Le Scanff, J., Mohammedi, I., Thiebaut, A., Martin, O., Argaud, L., & Robert, D. (2006). Necrotizing gastritis due to

Bacillus cereus in an immunocompromised patient. Infection, 34(2), 98-99.

19. Chaun, H. U. G. H. (1969). Massive gastric dilatation of

uncertain etiology. Canadian Medical Association journal, 100(7), 346.

20. Breslow, M., Yates, A., & Shisslak, C. (1986). Spontaneous

rupture of the stomach: A complication of bulimia. International Journal of Eating Disorders, 5(1), 137-142.

21. Baldassarre, E., Capuano, G., Valenti, G., Maggi, P., Conforti,

A., & Porta, I. P. (2006). A case of massive gastric necrosis

in a young girl with Rett Syndrome. Brain and development, 28(1), 49-51.